Horror isn’t confined to movies. This Halloween, keep a lookout the next time you head to a park, or maybe even your backyard. These tricks are always a treat — until they rear their spooky heads out of the murk.

VAMPIRE

Pacific lamprey

The Dracula of fish can be found in the larger streams and rivers feeding the San Francisco Bay and Northern California coast. A suction cup of sharp teeth, the lamprey latches on—its cheese-grater tongue repeatedly lapping at the skin of its victim. Jawless, insatiable, with a penchant for drinking blood, young lampreys only enter the water column after developing dagger teeth. When it’s time to breed, the eel-like fish swims upstream from the ocean in the dead of night. Though not immortal, the lamprey is one of the oldest living vertebrates, with its look virtually unchanged for 360 million years. Its mystical presence extends throughout its range in the Bay Area. Don’t be surprised if Dracula materializes out of thin air.

Trick: Hematophagy

There are only 30,000 species of blood-thirsty animals in the world. But living to suck blood is an evolutionary feat. Blood is toxic to most animals if not moderated. As lampreys grow into blood-sucking juveniles, their guts develop specialized iron-digesting bacteria.

THE IMPALER

Loggerhead shrike

Affectionately and aptly named the butcher bird, the loggerhead shrike is terrifyingly fearsome. For reasons some may think are unjustified, the shrike brutally impales its victims on thorns and barbed wire. The bird prefers its prey hidden in plain sight; shrikes thrive in open fields with few trees. With a striking display, the bird hovers over and dazzles its target before going in for the kill. With a black mask like a raccoon, this bird is a bandit of lives.

Trick: Prey preparation

The shrike isn’t out for revenge. A relatively small bird without talons or serrated teeth, the shrike needs to eat. By stabilizing its prey on sharp objects, it can easily tear it apart.

FRANKENSTEIN

California tiger salamander

The invasive barred salamander was introduced into California 50 years ago to be used as fishing bait. But in 2007, scientists documented barred salamanders breeding with the California tiger salamander to make one freaky genetic hodgepodge that the news media declared the “super salamander.” California tiger salamanders are endangered; the hybridization may help them as hybrids often have greater odds of survival. Conservationists worry that the tiger salamander will disappear as a distinctive species. Plus other native species, like the Pacific chorus frog and California newt, can’t compete — the hybrid is a voracious eater.

Trick: Hybridization

The hybridization is likely the first involving a formally endangered species, and one of a few known to survive, let alone flourish. The California tiger and barred salamander are as different, genetically, as humans and chimpanzees. Horticulturists have used the idea of hybrid vigor — the benefits gained from hybridization — for hundreds of years. Breeds and varieties are more closely related than different species, so it’s pretty rare for two species to interlace.

SPECTER SOUND

Black-footed albatross

A black-footed albatross call alternates between the sounds of a toad grunting in a pond, rapid-fire knocks on a door, screams of a frightened pig, and the thankless breaths of a hyperventilating rabbit. A cacophony of disembodied nature sounds wraps in one sleek and feathered ocean-faring bird — haunting the Pacific high seas for any who brave the bone-chilling oceans.

Trick: Over-sea migrations

It’s almost sinister how well the albatross takes over the Pacific Ocean. Ranging from the U.S. West Coast to Japan, this feathered siren has an ability to ward off death after thousands of kilometers of flight — a cause for concern for those sipping our hot pumpkin lattes in a cozy chair. Like many seabirds, the albatross is lightweight enough to make diving difficult. But the low weight makes it easier and more efficient to lift on lighter drifts, saving precious calories.

CORPSE EATERS

Dermestid beetle

These beetles do the dirty work of scavenging dead carcasses. Side-stepping morticians, dermestid beetles cut straight to the bone. Rather than using harsh chemicals that could potentially damage important clues in an investigation, many forensic scientists use these “hide beetles” to remove flesh around bone. Of unknown origins, the dermestid beetle is now widespread throughout Europe and North America — after all its past-its-prime snack is global. Lucky for readers, they don’t eat living flesh. But, they may be lurking in your home … waiting.

Trick: Forensic entomology

Post-mortem-feeding beetles have their ecological niche on each corpse — some like feeding on hairs, others dead skin. Some like fresh bodies, some like bloated. Using these clues, forensic scientists can help parse times of death.

JACK-O’-LANTERN

Jack-o’-lantern mushroom

Who knew the witch’s toadstool glows in the dark? You can find this orange mushroom huddled around the bases and stumps of hardwood trees. This fungus, also called the jack-o’-lantern mushroom, is a trickster in its own right: It is a poisonous look-alike to the treat chanterelle mushroom. It glows an eerie green in the woods at night, like someone lit a tea light in it — yet no one has carved this orange blob. Get out your flashlight to hunt for it, but turn it off when you’ve found one. Don’t expect it to tell you ghost stories if you illuminate it from below.

Trick: Bioluminescence

The jack-o’-lantern mushroom glows brightest during high spore production at its prime age. Chemicals produce a glow similar to that in the belly of a firefly. Unlike the on-demand glow pulses of a firefly, the jack-o’-lantern’s light is constant, waning only with the sun. Scientists believe that this helps with insect pollination. Hidden within its walls lie the secrets of one of Earth’s most beautiful spectacles: bioluminescence. Don’t fear; it’s not radioactive.

SKULLS

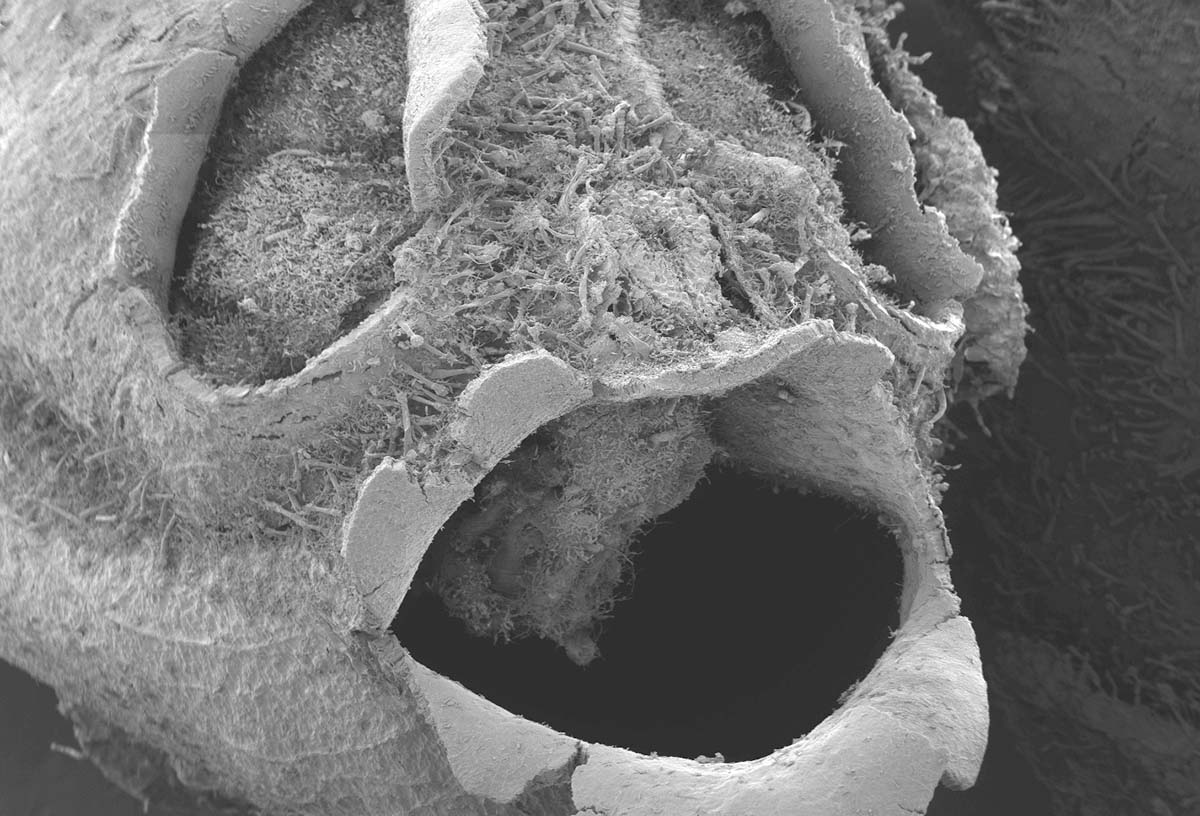

Snapdragon seed pods

The line between living and dead gets thinner for snapdragons at Halloween. The snapdragon, once a symbol of life and beauty, quickly becomes a symbol of death. Like a vampire sucking the youth out of a spring-blooming plant and drying it to a desiccated husk, the plant makes amends with its life by sending out seeds when the humidity and growing season die off. Once it’s ready to go to seed, the dragon’s head morphs into an ominous skull. But don’t worry: The plant resurrects as a lively flower in the New Year.

Trick: The co-evolution of flowers and insects

The flower has evolved not to waste precious, coveted pollen on just any animal. Like an iron trap door, the dragon’s jaws snap shut to prevent smaller bees from pollinating the flower. Hefty bees like the bumblebee can stubbornly push through the door. By nit-picking particular species to pollinate, the plant is more likely to have its pollen spread to the same species.