It felt like we were in a locker room, about to burst through the doors, ready to play ball. Sally Gale, head coach, I’d say if I didn’t know better, calls attention in her ranch barn where the Chileno Valley Newt Brigade gathers. Clad in reflective neon vests, counters, buckets and scrapers, the group is preparing for a night full of newt surveys.

The night is nigh. It’s a balmy 54 degrees—55 is a newt’s ideal temperature—and drizzly. “It just feels newty,” Gale says. She expects it to be a “big night.” On nights like these, volunteers can count 100 newts in a two-hour shift.

Gale inhales sharply and asks, “Now, what do we do if a car comes?”

“We stay four to eight feet off the roadway and point our light downwards,” says Michael Kraus, one of the more experienced of around 30 active and 200 semi-regular volunteers.

At the end of the pep talk, I fully expected them to put their hands together and yell, “Newt glory!” before parting ways. Alas, they did not, but we were in for an exuberant car ride.

Every year California newts (Taricha torosa) migrate across the Chileno Valley Road, from the woodland hills to Laguna Lake. Once they reach the water they find a mate and breed, with the most newts arriving between November and March. This is the deadliest time in a newt’s life.

Bumbling over the asphalt, the six-inch amphibians are no match for drivers on the roadway. Because newts travel en masse, a single car and a few seconds can wreak havoc on a population.

In one study of the 2020–2021 winter near Lexington Reservoir, in the Santa Cruz Mountains, scientists found that 14,000 newts tried to cross the road and 40 percent died—one of the largest rates of roadkill reported for any wildlife species in the world.

The edge of Laguna Lake runs parallel to Chileno Valley Road for nearly a mile. This stretch of road is the closest entry point to the lake for newts traveling to their breeding grounds. One night three years ago, Gale jumped out of her car after seeing a dead newt and ran the entire mile (in heels no less) to observe what would ultimately change her life: 45 dead newts and only five alive.

For most of her career, Gale was a pediatric social worker in a tertiary care facility, meaning she saw complicated cases.

“I was making their suffering a little lighter,” she said. “They bring you into their life and trust you with a very serious thing that’s going on in their lives. It’s a privilege.”

When she noticed the newts suffering, she felt called to action. Her empathy spilled onto other species.

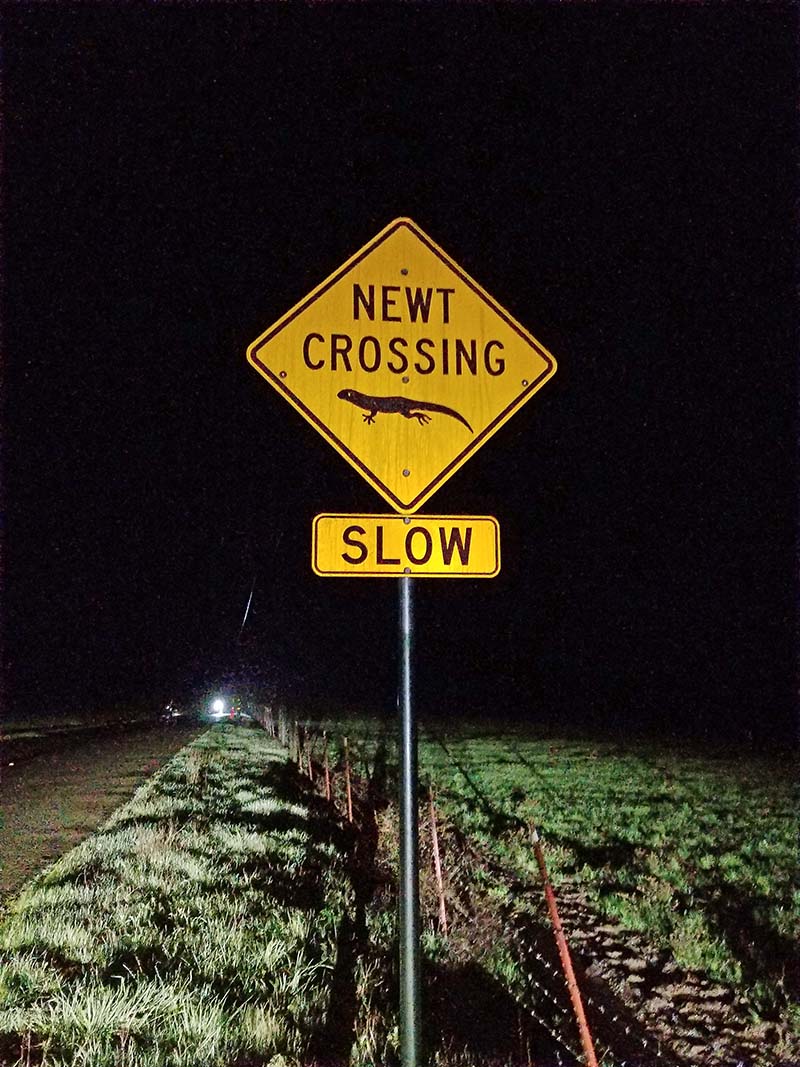

After seeing the newts struggling to cross the road that fateful night, she called upon people, biologists and non-biologists alike, to listen to her idea of a more newt-friendly road. Then she went out to the road every night for the first year, and founded the Chileno Valley Newt Brigade. Now, after several years, her increasing numbers of volunteer newt protectors want a mortality study. There are newt crossing signs along Chileno Valley Road, but Gale says the brigadiers would like to know whether or not the population can survive the road mortality. And if it can’t, how many years do we have left before they’re extirpated?

Tonight, I’m paired with Bo Kearns on what Gale labels the middle-east quadrant, a roughly quarter-mile stretch of road on the edge of the eastern newty segment of Chileno Valley Road. Outside our flashlight tunnel vision, the night was pitch black — the only sight was the orbs of rain falling in front of us and the occasional car’s headlights. Kearns was in charge of the two counters, one to count the dead and another to count the living. I became the iNaturalist observer.

We set off in parallel, facing the same direction traveling east, one on each side of the road, scanning the ditches to the center line and back again with a flashlight – looking for any inkling of color along the road. When we made it to the east cone, we turned around and covered the road in the opposite direction, repeating the sequence until our shift was up at 6:30 p.m. My eyes glued open, I found eyeshine in the smallest things: dew drops on blades of grass and eight-eyed spider shimmers.

At exactly 5:35 p.m., I found my first California newt. “You got one?” yelled Kearns. We recorded it on iNaturalist, advanced the counter, picked it up and placed it on the other side of the road in the direction it was traveling. We took the photos with our backs facing the woods so that volunteers could decipher the direction of travel.

Just a few minutes later, reality sank in.

Kearns whispered in a hollow, hushed voice, like a doctor when a surgery goes awry. “He didn’t make it.” The newt was a mash barely recognizable. Just one foot was spared from the path of a tire, seemingly reaching for safety—the other side of the road just out of grasp. It had the tell-tale yolk-yellow side stripe. A grating scrape of the asphalt quietly announced that another newt met its fate. Kearns gingerly picked up the corpse from the road, so we didn’t double count. With its gentle placement on the ditch, its quest violently ended.

I imagine the long, fraught journey of the newt. After an inch of rain falls, the newt, driven by its urge to pass on its genes, travels around three miles of terrain to find its mate. Newts can live up to 20 years in captivity. That means wild salamanders have less than 20 seasons to breed. At the lake, if it makes it, the male newt will place a spermatophore on underwater substrate to be picked up by its mate and the larvae will stay in the water for about five months before traveling back on the same journey, to repeat this until its (hopefully timely) demise.

Rick Parmer, a member of the brigade’s steering committee, has found that five to ten cars pass per hour and an individual newt can take 15 to 30 minutes to cross the road. The chances are slim.

Later, Gale’s words echoed in my head: “We can’t just keep going out there every year and picking up the newts for three months. That’s really not much of a solution.”

We were not in the busy quadrant, and our work yielded four total live newts and two dead newts. Others would find roughly 40, dead and alive. This year’s iNaturalist project, the 2021-2022 Chileno Valley Newt Brigade Winter, has 1,623 total observations of the California newt and 88 rough-skinned newts, at the time of writing. The brigadiers have yet to tally deaths this season. Still, it was split about evenly between the living and the dead in previous years—similar to other studies in different areas.

Despite the joy of scoring another live newt, the team dreads the overall scoreboard.

“We’re in this for the long haul. But, unfortunately, these species are not giving us very much time,” Gale said. “It’s a race against extinction.”