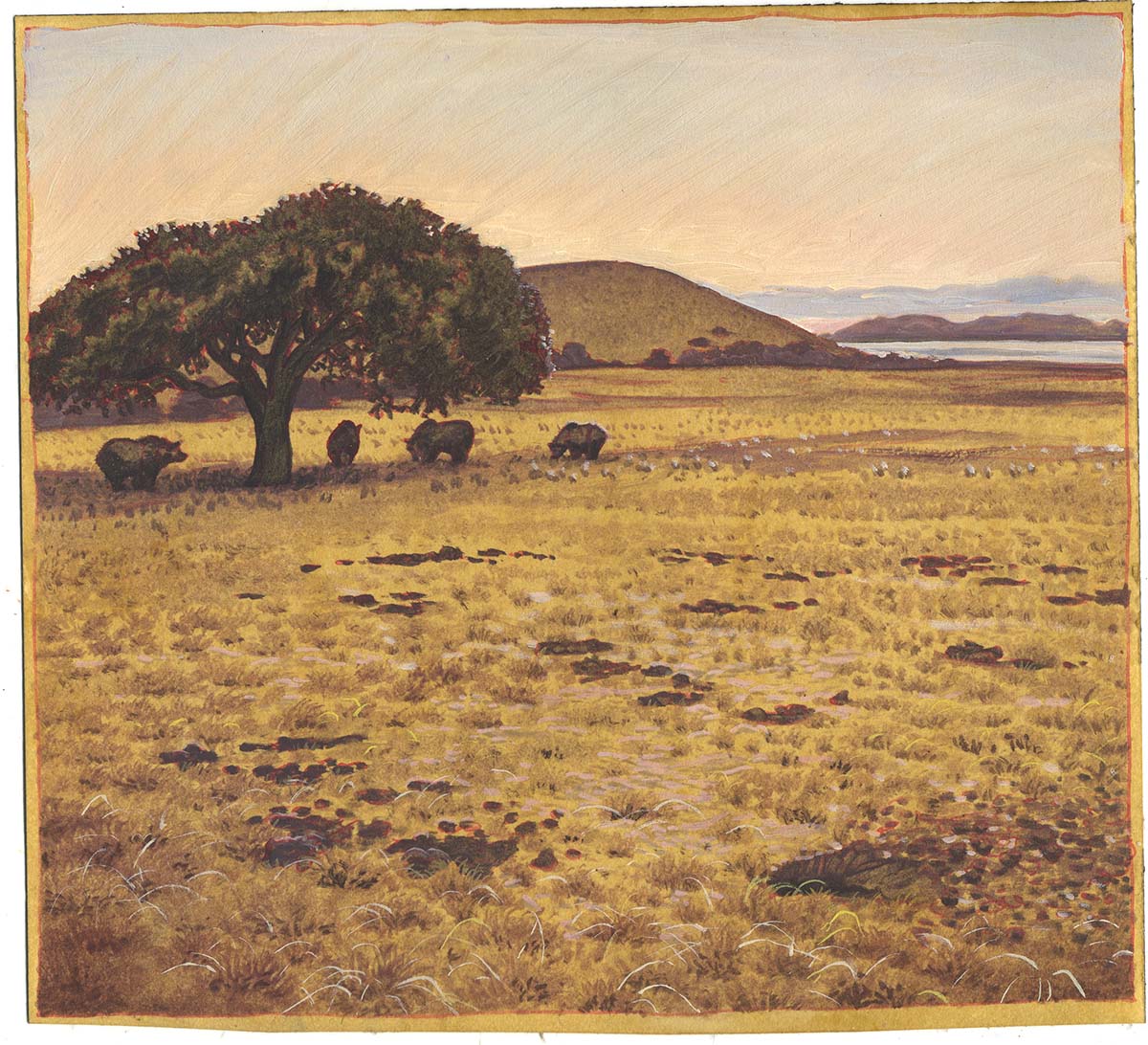

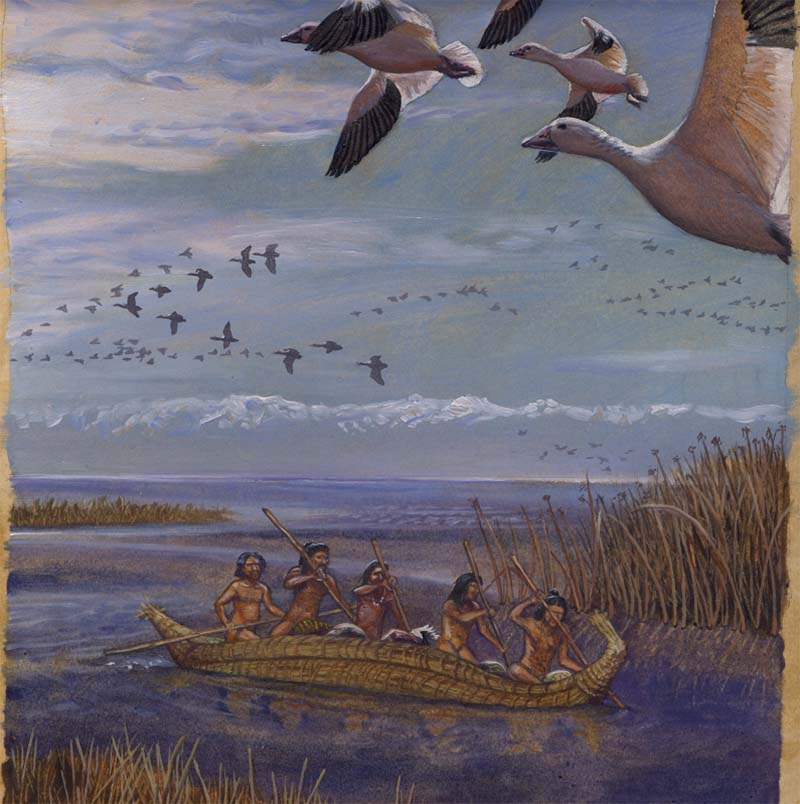

Ever since she was a little girl in the 1980s, Laura Cunningham wondered how the landscapes of her hometowns of El Cerrito and Kensington appeared hundreds of years ago. In high school and then later as a college student at UC Berkeley, Cunningham spent hours in libraries researching tule elk, native grasslands, and grizzly bears. She learned how diverse Indigenous groups used cultural burns to enhance oak woodlands and wildlife habitat. She studied historical biological and botanical surveys that evoked images of vast meadows, vernal pools, and native bunch grasses. She read stories of grizzly bears that wandered down to the beach and used their massive paws to scoop up salmon from ancient rivers. It was a landscape of abundance where rivers were wild and untamed. She pored over historical accounts of early California — diaries from Spanish missionaries, and later, Gold Rush settlers. Cunningham remembers reading an account from an explorer in the 1840s where he describes seeing a large, spotted cat in the Tehachapi Pass. “There were jaguars in California!” she notes.

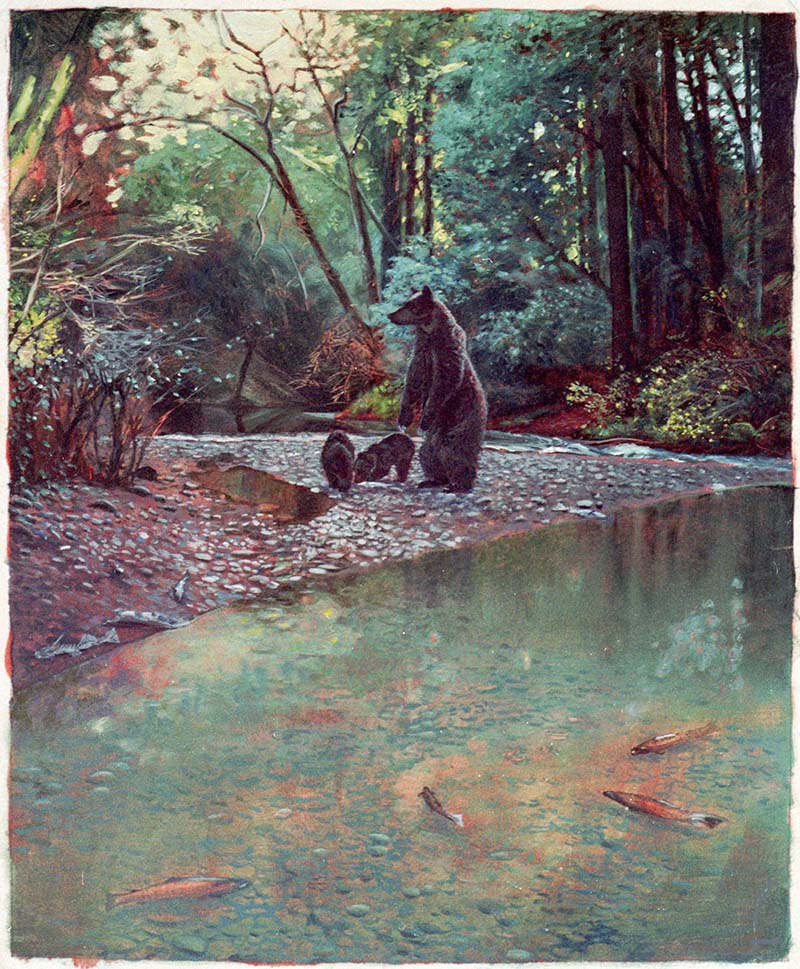

As a naturalist who loved the outdoors, Cunningham didn’t spend all her time in libraries. Doing fieldwork further fueled her passion for uncovering what was lost. After college, she got a wildlife biologist position surveying frogs, toads, and salamanders in the Sierra Nevada region. Observing the endangered yellow-legged frog piqued Cunningham’s curiosity on how species decline. Later, working as a fisheries biologist for the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, she further pondered the loss of wildlife. She did stream surveys for salmon, measuring spawning gravels. Spending days walking up and down the streams of the Smith River, she captured her observations in oil paintings. “I could envision red bodies of salmon populating winding, untamed rivers hundreds of years ago,” she says.

Along with her fisheries work, Cunningham spent hours watching, photographing, and sketching wildlife. She wanted to see wild animals in their natural habitat, not in zoos where captivity would alter their behavior. Cunningham watched condors soaring in the wild. She listened to bull elks bugle and watched them crash antlers, competing for females at the 2,600-acre Tule Elk Preserve at Point Reyes National Seashore. Back at her studio, she used her notes, photographs, and sketches to capture her observations in watercolors.

Watching native wildlife inspired Cunningham. But, she also wanted to observe animals that once filled California’s landscape. During the 1990s, she traveled to Yellowstone National Park to observe wolves and grizzly bears in the wild. There, she met a group of bear watchers that set up spotting scopes and binoculars in different park locations to watch grizzly bears. “It was amazing to watch them in their natural habitat,” she says.

One day a bear watcher said, “a pack of wolves just took down an elk!” The group followed her to the spot of the kill and watched the wolves feed off the carcass. Then, the wolves left. Next, grizzlies came to feed on the carcass, along with golden eagles and ravens. The food web was unfolding before their eyes. Cunningham envisioned this happening in California hundreds of years ago with condors feeding off the carcass.

Over several years, Cunningham compiled her notes from trips to Yellowstone, fieldwork, and academic research. She organized her information in folders on different topics — redwoods, salmon, tule elk, predators, and more. Interviewing tribal elders in the 2000s, she learned about what their land means to them. Chemehuevi tribal elder Phil Smith, who lives along the Colorado River, spoke to Cunningham about his and his people’s connection to the desert. Now in his 80s, Smith remembers stories of his father’s birthplace, a village site long vanished in the Mojave Desert’s Ivanpah Valley. Desert shrubs that have medicinal and practical uses, Indigenous songs about the cultural landscape, and an ancient trail leading to sacred hunting grounds in the Clark Mountain are part of his people’s heritage. Now, he told Cunningham, energy development threatened this land and the memories of it. He hoped by sharing his story, he could help preserve the land. He could not — it was developed. “Deep memories such as these need to be respected, and backed up with support for the Indigenous people sharing this significant knowledge,” Cunningham says.

After 20 years of research, several oil paintings, and four years of writing and rewriting the manuscript, Cunningham had a book, which was published by Heyday press in 2010 and called A State of Change: Lost Landscapes of California.

The book has been well-received, though not by everyone. “On book tours, I sometimes got angry reactions from people,” she says. One man told Cunningham, “It sounds like you want to erase civilization and have us return to the wild.”

She responded, “No. I’m a realist. If I lived in Europe, I might be studying ancient Rome. But, I grew up in California and I wanted to study our ancient landscape. I want to preserve the relicts of our wild past.”

Cunningham mentions there are places in the Bay Area where people can still see wild relicts. Native grasslands and purple needle grass are at Tilden Regional Park’s Inspiration Point and Nimitz Way in the Berkeley Hills. Jepson Prairie Preserve in Dixon has vernal pools. People can watch tule elk in their natural habitat at Tomales Point at Point Reyes National Seashore. They can observe condors at Pinnacles National Park. Salmon spawn at Lagunitas Creek in Marin County.

Cunningham’s book is out of print, but that’s not the end of the story. She is adding the manuscript to her new website, still under construction, each chapter at a time, including text that was not in her original book. She’s also updating chapters, such as the one on fire ecology with new information. In October 2019, the Karuk and Yurok Tribes invited Cunningham and other artists to sketch a cultural prescribed burn on the Klamath River watershed in northwestern California. Tribal members, CalFire, the U.S. Forest Service, and other groups monitored the fire, ensuring it did not spread or burn any big trees. “Over 100 years of fire suppression combined with the effects of climate change, has led to megafires in the last decade,” Cunningham says. “It’s now California’s new normal. In the early 1900s, U.S. officials told Klamath tribal members they would arrest them if they set fires to the landscape. Tribal members have a lot to teach us about how fire is an important part of a healthy ecosystem.”

Now, Cunningham is focusing her efforts on protecting wild places and wildlife. Years of researching lost landscapes inspired Cunningham to become a conservationist. She’s concerned about how wolf hunts in Montana, Idaho, and Wisconsin could devastate these predators. She serves as the California director of the Western Watersheds Project, which is suing the Department of Interior to restore protections to gray wolves under the Endangered Species Act. “Wolves need to disperse and move,” she explains, adding, “look at OR93.”

A collared gray wolf, known as OR93 walked all the way from Oregon to Southern California. He traveled in areas where gray wolves had not been in 100 years and longer. A game camera in Kern County captured his whereabouts. Sadly, a vehicle struck and killed the wolf when it crossed a busy Southern California highway in Lebec on November 10, 2021.

Despite these losses, Cunningham has hope for the future. She points to the development of the largest wildlife corridor in the world, which will help wildlife cross Highway 101 in Agoura Hills, near Los Angeles. “I believe people and wildlife can coexist,” she says. “I know California is too populated to return to the abundant landscapes and wildlife we once had. But one of the larger takeaways for me in my conservation work is to value your backyard, your home area, your neighborhood — its natural and cultural heritage and history. In the 1980s attending UC Berkeley we rallied around the goal ‘Think Globally, Act Locally.’ I still live by this. Act to protect your backyard, because it matters greatly.”