Big Basin State Park is not the lush, shady ancient forest it once was. In August 2020, 97 percent of the old-growth forest nestled in the heart of the Santa Cruz Mountains burned in the devastating CZU Lightning Complex fire. Eighteen thousand acres burned, and the iconic park visitors center, lodge, staff homes, and other buildings were reduced to ash. An eerie silence hung over the scorched earth and skeletal trees.

Teresa Baker was shocked when she saw what remained a few months after the catastrophe.

“It seemed like a warzone,” says Baker, an advocate for diversity in the outdoors who serves on a committee advising the reimagining of Big Basin. “I didn’t hear any birds. I didn’t see any green. Nothing.”

Nearly two years later, Big Basin will partially reopen to the public this weekend on Friday, July 22. Though many trees were severely damaged or killed by the blaze, most of Big Basin’s redwoods (Sequoia sempervirens) survived, even in areas where fire ravaged the canopy. Fuzzy bursts of bright-green new foliage spurt in improbable directions from blackened redwood trunks.

“There are a lot of people out there that had their first inspiring moment in a redwood forest at Big Basin. Most people who’ve been in redwoods remember that first moment.”

Ben Blom, Save the Redwoods League

“We pushed very hard to reopen as soon as we thought we could do it safely,” says Chris Spohrer, Santa Cruz district superintendent for California State Parks. “We can expand that access going forward, but we felt that it was our responsibility to let the public back in to experience the forest going through these early stages of recovery. I think it will really help people to process the loss, and also envision a resilient future for the park.”

Beyond the physical work of debris removal and reconstruction, the California State Parks Department invited the public, Indigenous leaders, park neighbors and community advocates to a series of workshops and online surveys gathering input for a renewed vision of the park’s future. This reimagining project aims to imagine, plan, and design a future Big Basin that is more inclusive, accessible, and resilient in the face of fires, droughts and other threats exacerbated by climate change, with the goal of fully reopening the park in 2030. Until then, park workers and allied organizations have banded together to bring the visitors back into Big Basin so they can witness the forest’s recovery firsthand.

“Expect to see a lot more sunlight hitting the forest floor,” says Spohrer. “The canopy is much sparser than people will remember. There are many smaller shrubby plants and grasses, so the forest floor is quite green.”

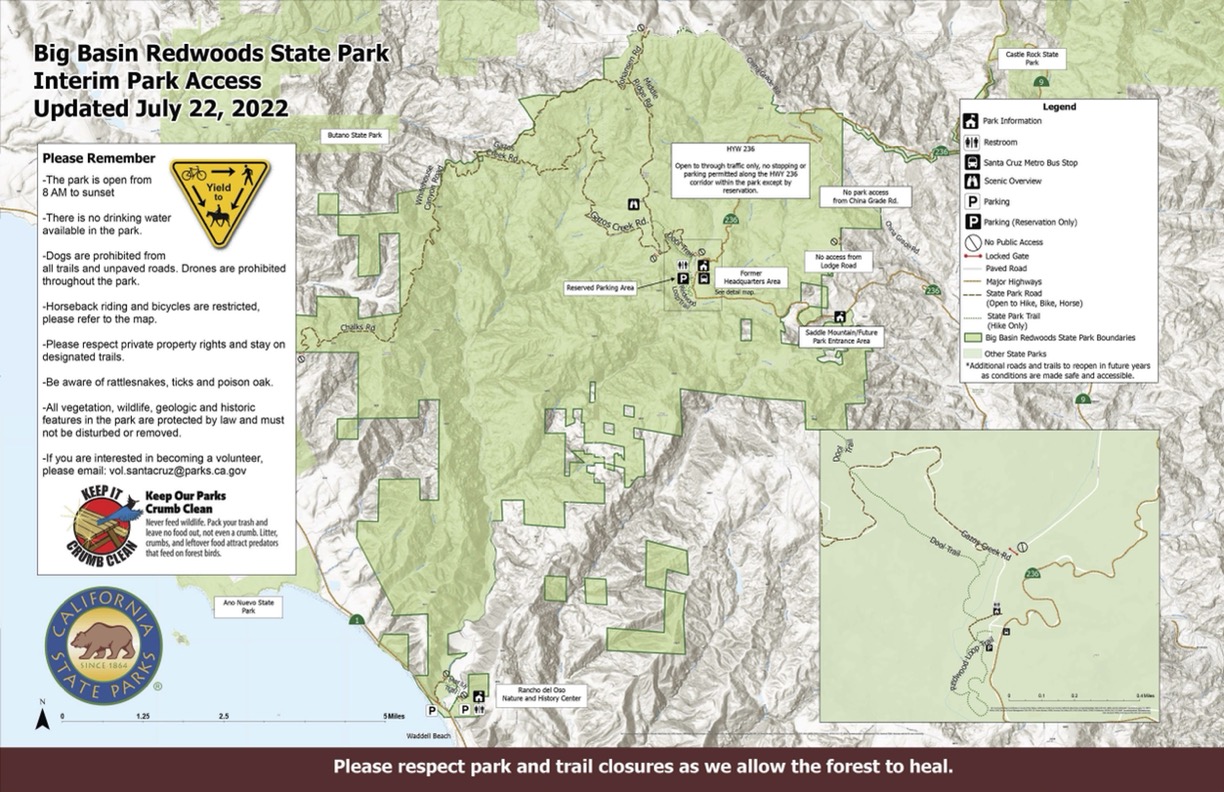

The park’s main road, Highway 236, has been cleared. The iconic Redwoods Loop Trail, the Dool Trail, and 18 miles of backcountry fire roads will be available for hiking and biking. Reservations can be made online for limited car access to Big Basin for day use, with 50 total parking spots available for $8 per day. A new Santa Cruz Metro bus route will go from downtown Santa Cruz to the center of the park four times a day on weekends, allowing visitors without vehicles or reservations to access the reopening as well.

California’s Oldest State Park

Established in 1902, Big Basin is California’s oldest state park. Its forests contain the largest old growth coastal redwood stand south of San Francisco, with many trees that are hundreds of years old and some that are over a thousand years old. These iconic behemoths played a pivotal role in California’s conservation movement, inspiring organizations like the Sempervirens Fund and Save the Redwoods League to advocate for protecting the lands that would later become Big Basin from logging and development.

“Today we have less than 5% of the old growth redwood forest that was in California in 1850,” says California state parks senior environmental scientist Joanne Kerbavaz. “Big Basin is special because it was one of the first places in California where people realized that they had to come together and take action to save a special resource before it was lost.”

Its iconic old growth redwood groves are beloved by generations of visitors from the San Francisco Bay Area, Santa Cruz, and beyond. The wilderness is accessible within a one or two hour drive for millions of people, offering a humbling look up into the cathedral-like sunbeams filtering through the canopies of the ancients.

“There are a lot of people out there that had their first inspiring moment in a redwood forest at Big Basin,” says Ben Blom, director of stewardship and restoration for Save the Redwoods League. “Most people who’ve been in redwoods remember that first moment.”

But Big Basin is not the same park that visitors might remember.

Limited Access

Before the fire, Big Basin hosted 1 million visitors per year. It was equipped with its own electrical grid, sewage system and wastewater treatment plant, staff housing and hundreds of campsites. All of that infrastructure is now gone. There is currently no drinking water available in the park; electricity and communication lines have yet to be restored, and it will take years to repair 73 miles of severely damaged trails and build new campgrounds. The number of visitors allowed in the park is limited by the reservation system in order to protect the recovering forest and stay within the spaces and services currently available to the public.

Temporary amenities including chemical toilets and an interpretive ranger kiosk have been installed at the heart of the park, where the reopened trails begin and the park headquarters once stood. Despite the great strides in making the roads and trails safe for visitors in designated areas, only a fraction of the park has been cleared. Away from reopened roads and trails, the majority of the park remains dangerous, with hazardous dead trees and unstable ground.

So far, 28,000 trees have been removed from near Highway 236, trails, and parking. Most of them were fully scorched Douglas firs, along with dead understory trees such as tanbark, madrones, and live oak.

In the heart of the park, a blocked-off clearing strewn with burnt branches gapes where the visitors’ center once stood. The wreckage and contaminated ashes have been removed, and the hole they left behind has been filled in. But the parks department chose to leave the headquarters’ unscathed stone steps leading up to nowhere as a reminder of what used to be.

“The loss that we’ve experienced collectively as a community, of just the sense of place and the history, has been really hard on a lot of people,” says parks superintendent Spohrer.

The Mighty Redwoods Persisted

The fire that engulfed Big Basin was a culmination of extreme weather: months into a severe drought, during an extreme heat wave with hardly any of the typical fog rolling in from the coast, and finally a dry lightning storm accompanied by high winds.

But redwoods evolved with fire, and are uniquely capable of taking on both the blaze itself and its aftermath. Redwood bark – which can grow as thick as a foot on older trees – shields the inner layers from flames. After the fire has passed, tannins infused in the tree’s wood act as preservatives, protecting any open wounds from insect or fungal infestation in the aftermath. These tannins are the same chemical that give the wood its characteristic rusty hue.

Most tree species are in big trouble if a fire damages their branches and lays waste to their canopy of leaves or needles. These trees will die, and must rely on new seedlings to repopulate after a canopy-ravaging fire. Redwoods, however, have a remarkable ability to regrow their canopies. After severe fire damage, they can sprout new foliage straight from their trunks and branches – a phenomenon known as epicormic sprouting. They can also send up sprouts in rings around the base of the tree, known as basal sprouting.

“Unlike most conifers, redwoods have dormant buds both at their bases and along their trunks and branches,” says Kerbavaz. “The dormant buds are suppressed by plant hormones produced by the tree. But if the dominant growth is injured or lost, the dormant buds can sprout and grow new trunks, branches and leaves.”

If you look closely, you might notice that many old growth redwood trees tend to grow in rings. These “fairy rings” are echoes of basal sprouts that once burst from the ashen ground around an ancestral old growth tree that burned in a long-ago fire and have since become fully grown trees themselves.

“With time, the rings of bright green sprouts around the redwoods that have been burned have the potential to become the next ring of old growth trees,” says Kerbavaz.

While tragic, the severity of the CZU Lightning Complex Fire gives forest ecologists a unique opportunity to study how redwoods young and old regenerate post-fire.

“We think of fires as these short term events, but redwoods can burn for up to a year,” says Laura McLendon, conservation director at the Sempervirens Fund. She saw this herself about six months after the fire while doing field work in Big Basin. “I came across a tree that was still smoking like a chimney. This fire was pretty high up in the canopy, in the trunk of this tree.” Looking closer, McLendon found green sprouts popping up around the burning tree’s base. “I saw green sprouts on the trunk and fire at the same time.”

Even if their tannins and bark aren’t enough to protect them from fire, redwoods can survive severe damage to their heartwood, the inner layer of the tree that supports the entire organism and allows them to stand tall. As long as the living layer between the bark and heartwood remains mostly intact, the redwood can continue ferrying nutrients and moisture and continue growing. This living layer is called the cambium. Fire within the base of a tree can burn the heartwood and even carve out a cave, but as long as there’s a layer of cambium in even just a part of the tree, the redwood can recover and survive. The remaining cavities can be big enough to stand inside the burned out tree, a popular activity for visitors.

Madrones, Firs, and Oaks

While redwoods and their fuzzy, bottlebrush sprouting are remarkably resilient, other trees found in Big Basin’s forest haven’t fared so well. Madrones, Douglas firs, tanoaks and live oaks are often killed by intense fire – but sometimes even they can make a comeback.

“These trees are all resilient to fire by actively resprouting from their bases when the top is killed or removed,” says Kerbavaz. “In Big Basin, most of these trees now have sprouts that are already several feet tall.”

Madrones can look like they’ve been killed by fire, but even if their trunks and canopies burn, their root system can survive below ground and resprout new branches from the base. The forest floor is now blanketed in California lilac shrubs (Ceanothus spp.), yellow bush poppies (Dendromecon rigida), and yerba santa (Eriodictyon spp.). California lilacs fix nitrogen in the soil, making them key players in rebuilding the forest ecosystem after disturbance.

From removing hazards in the months after the blaze to preparing to welcome visitors back to the park, the restoration of Big Basin has been a monumental task.

Chris Young, a member of the Big Basin volunteer trail crew, isn’t sure visitors will be prepared for how remote the park feels, or how utterly the forest has been transformed.

“The way the forest was before the fire, it will never be like that in our lifetimes again,” says Young. “These trees can live 2,000 years. They’re not in a hurry. They’re gonna take their time and grow back. We’re gonna have to be patient and just enjoy what change we can see while we’re here.”

Once the most dangerous parts of the cleanup following the fire were taken care of, Young’s trail crew began working to restore trails by rebuilding footbridges and filling in pits created when tree roots continued to burn underground. Some trees were found smoldering as long as a year and a half after the fire.

Reimagining the Future of Big Basin

While the redwoods’ resilience is remarkable, the sheer amount of work left to restore the rest of Big Basin is daunting, and requires cooperation from multiple groups.

The reopening of the park came about thanks to extensive collaboration between conservation organizations, state and local park agencies, the reimagining project advisory committee, and the volunteer trail crew. Friends of Santa Cruz State Parks, a non-profit organization that supports operations in 32 parks and beaches throughout the county, will be handling visitor services such as the reservation system and interpretive programs.

“It’s a miracle,” says Bonny Hawley, executive director of the Friends of Santa Cruz State Parks. “It’s a case study of government and non-profits and the community working together. To think that 97 percent of the park burned, and less than two years after the fire, people are being allowed to go back in to recreate and to observe the park — no one expected that to happen. Everybody thought it would be at least five years.”

While construction crews continue to haul out scorched trunks and trail volunteers build new bridges and paths, another kind of reconstruction is underway: reimagining Big Basin’s future.

The reimagining project aims to rebuild Big Basin to be more resilient to climate change, as well as more inclusive, accessible, and welcoming to communities that have previously been excluded from state parks. Amid the debris and heartbreak left behind by the fire is a unique opportunity to reconsider the structures and meaning of a park that has existed for 120 years.

The advisory committee guiding the reimagining project is made up of representatives from conservation organizations, chairpeople from the Amah Mutsun Tribal Band and Muwekma Ohlone Tribe, and outdoor equity advocates, including Teresa Baker. The committee is currently considering a variety of changes to how the park is designed and run, taking the ecological reset caused by the fire as an opportunity to challenge and rethink assumptions about other aspects of the park.

A major point of discussion is the role of prescribed burns. While most old growth redwoods have been affected by wildfire at some point in their lifetime, California has recently experienced less frequent but more intense fires. These fires raze through dry underbrush and accumulated fuel, and can burn so hot that they obliterate the cones of species like knobcone pine and Monterey pine, which normally rely on heat to release their seeds.

“We’ve done fire suppression for almost a hundred years across California,” says Ben Blum of the Save the Redwoods League. “We’ve created these conditions that are causing more intense fires to occur. Combine that with climate change and drought and it’s really setting the stage for these catastrophic wildfires.”

The reimagining committee has been in deep conversation on how to learn from Indigenous forest management techniques and reincorporate prescribed burns at Big Basin going forward. Reducing dead trees and other forest floor fuel and placing park buildings out of the way of burn areas are other strategies being discussed to encourage more frequent, milder fires that can benefit the forest.

The cluster of historic buildings at the foot of Big Basin’s tallest and oldest redwood grove not only burned to the ground, but also burned hotter and with more toxic substances than elsewhere in the park. Even before the fire, the heavy traffic attracted to the park headquarters put pressure on fragile old-growth root systems. In a reimagined Big Basin, new buildings could be built on the periphery of the park instead, with a shuttle system to transport visitors throughout the park instead of individuals driving all the way in. This would also minimize parking lots under the redwoods, and visitors would spend less time idling in traffic jams.

Baker agrees that having fewer structures and rebuilding them farther away from the park’s most popular areas is the way to go, even if it’s not as convenient. In her role on the reimagining committee, Baker is keen to keep thinking about Big Basin’s long-term future.

For Baker, reimagining Big Basin includes reaching out to underrepresented communities and inviting them into the park. This means changing storytelling around the park and its significance, from discussions of setting aside ceremonial space to creating more inclusive signage in multiple languages and interpretive programs that include Indigenous knowledge and the history of people of color in Santa Cruz County. The future of fire mitigation is also being reimagined, such as drawing upon Indigenous knowledge and reintroducing cultural and prescribed burns to prevent future out-of-control wildfires.

“It’s hard for humans to think on longer timescales beyond our own lives, much less on the timescale of a redwood,” says Kerbavaz. “Part of the awe of this forest is to have this window into a world that takes us so far into the past, as well as giving us hope for the future.”

Big Basin holds a unique legendary status as one of the most visited state parks. It is deeply beloved and fondly remembered by thousands of visitors. Baker believes the reimagining is a unique opportunity to embrace Big Basin’s powerful legacy as a place that can tell a more complete set of stories about California’s history and people.

“Sometimes those stories aren’t pretty,” says Baker. “It’s about the removal of people. It’s about not honoring legacies that were already there, doing away with them. So it’s a lot that the park has had to take into consideration around this whole process.”

When Baker returned to Big Basin six months after her first post-fire visit, she was astonished by how much the forest had changed.

“I started seeing green. I started hearing the birds, and deer were running around,” says Baker. “Five years from now, I would love to see how it has come back. I would love to see how the community has adapted, because it will not be the same.”

Corrections

An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that bush poppies (Dendromecon rigida), and yerba santa (Eriodictyon spp.) are capable of fixing nitrogen, and that California lilac (Ceanothus spp.) is a grass. The text has been corrected.

Additionally, an earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that Chris Spohrer is the superintendent of Santa Cruz County Parks, but he is the superintendent of the Santa Cruz State Parks. The text has been corrected.