The Anna’s hummingbird perches, backlit, on a power line above me, on my walk through North Berkeley. Its unmistakable call follows me way down the street, like two pieces of styrofoam, rubbing together: scree-scree-scree-scree!

The hummer’s a familiar resident in these parts, though. What I’m straining to hear are any migrants passing overhead. Maybe a Swainson’s thrush, a warbling vireo, or a western wood-pewee.

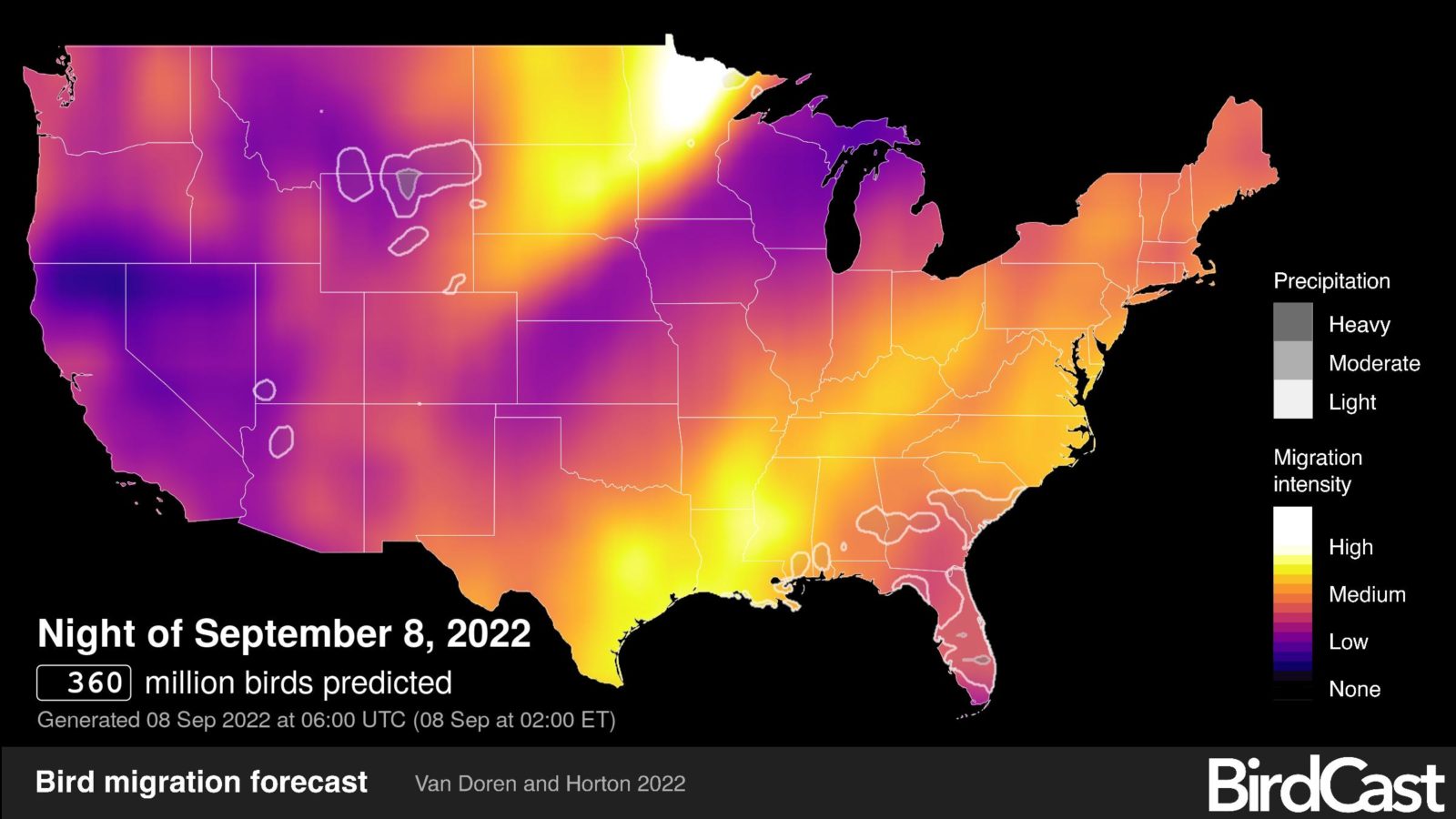

BirdCast, an online hub for bird migration information, is my guide on this search. In addition to providing me a list of likely migrant species, the website also features a dashboard showing me that on the previous night in early September, some six thousand birds flew over Alameda County.

Three thousand miles away in northwestern Pennsylvania, near Lake Erie, Katie Andersen sits by her window. She’s listening too, to the birds cloaked by night.

During peak times, some half-billion birds may move across the U.S. in a night. Thanks to BirdCast’s website, Andersen and I are both able to track a little piece of this flow from opposite ends of the country. For Andersen, who checks BirdCast daily during peak migration season, BirdCast is a tool that helps her tune into what she calls the “feathered river.”

“A river of birds. But they’re all moving overhead,” says Andersen. “And everybody’s going on with their lives underneath, sleeping or going to work, just not aware of this incredible phenomenon.”

This bird-river is being monitored by the same radar installations used to track weather patterns across the country.

One hundred forty-three U.S. government radars, looking like giant golf balls perched on pedestals 90 feet above the ground, are spread across the lower 48 states, collecting the data BirdCast uses to track and forecast migration. (Locally, there’s one in the South Bay and one in the Sacramento area.)

Of course, they weren’t designed to collect information on birds, says Kyle Horton, an assistant professor at Colorado State University, who studies bird migration and is part of the BirdCast team. These big radars are just doing their radar thing: casting out pulses of radiation that bounce off the things they encounter and detecting what comes back. Sometimes the rays hit large thunderstorms, dense with water. And sometimes they encounter birds, which are also dense with water.

“You could think of them as like big rain droplets, from the radar’s perspective,” Horton says. Helpfully, migratory bird-rivers are far less water-dense than rainstorms, so their signal is weaker. That’s one way researchers isolate the feather from the weather.

BirdCast is, essentially, doing “the opposite of what meteorologists are doing,” Horton says. Meteorologists toil to scrub the scrub jays from their analyses. “We are removing the weather and maintaining the birds,” Horton says. “That’s the fun of it.”

Since the spring of 2018, BirdCast has been crunching radar-gathered data and presenting it online on a migration tools tab, so you can see birdflow stats in real time. BirdCast’s makers — a team of specialists at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and Colorado State University, among other collaborators — also use the data to show historical trends and to model future migrations, which is how I know what to expect. The model has proven very good at predicting migration routes as well as its peaks and flows, according to a 2018 paper in Science by Horton and Benjamin Van Doren, from the University of Oxford.

Knowing when birds are on their way could help people mitigate the anthropogenic threats birds face during these dangerous journeys — like artificial lights that can fatally lead birds astray, wind turbines, and air traffic. Horton’s team is testing out that idea now. In a Texas pilot project called Lights Out Texas, BirdCast can send people automated email alerts for 19 cities there. If a particularly large number of birds are on their way over, subscribers will hear about it and know it’s time to turn off the nonessential lights, close their blinds, and point lights downward.

For bird lovers like Andersen, BirdCast has made tuning into the yearly cycles of birds much, much easier. In 2021, BirdCast garnered 1.8 million page views by nearly a half-million people.

“Even if I can’t see the birds, I can hear them. And even if I can’t hear them, then I can go into BirdCast,” Andersen says. “The natural world is doing its thing, whether I’m here or not …. But how cool is it that I’m able to bear witness to it?”

Thousands of thrushes and shorebirds call out as they soar over Andersen’s home, audible even through her window. As she listens, she records their calls on her phone, imagining the flocks flying just overhead.