This is a series on NatureCheck, a scientific collaboration looking at indicator species to assess East Bay habitat. You can read the full report here. (Illustration by Jane Kim)

Other STORIES IN THIS SERIES

How Healthy Is the East Bay’s Habitat? An intro to NatureCheck, and how you can help.

Measuring Migration From the Hills to the Sea Rainbow trout depend on healthy streams.

What Bats Tell Us Meet the Bat Brigade, looking out for the East Bay’s 16 bat species.

Grasslands are by far the most widespread among the vegetation communities in network lands. Half of the 225,000 acres assessed in NatureCheck are characterized as grasslands, an ecosystem vital for both wildlife and native plant biodiversity. The ecosystem also sequesters carbon and supports a wide diversity of pollinators.

East Bay grasslands are undeniably beautiful and representative of some of the best nature the Bay Area has to offer. Yet these ecosystems are far from untouched. Before the Spanish arrived, Bay Miwok peoples managed the grassy ridges and valleys of the Diablo Range through seasonal burning and coppicing. Fires kept the woodlands open for grazing animals like tule elk and pronghorn antelope, while sedge and bulrushes provided material for basket weaving. Once the Bay Miwok were dispossessed of their land, first by the Spanish and later by Mexicans and Americans, East Bay grasslands changed quickly. Wild oats and bromes moved in. Cattle and sheep replaced elk. Mexican ranchos and then American cattle ranchers divided up the range, suppressed fires, channeled waterways, and fundamentally changed the ecosystem.

Today’s grasslands represent the culmination of this human ecological history. In the Diablo Range, for instance, the hills glisten with both native purple needlegrass and nonnative slender wild oats. Raptors soar above. Amphibians breed in stock ponds. And at the center of it all, a small mammal builds a burrow.

California Ground Squirrel

(Otospermophilus beecheyi)

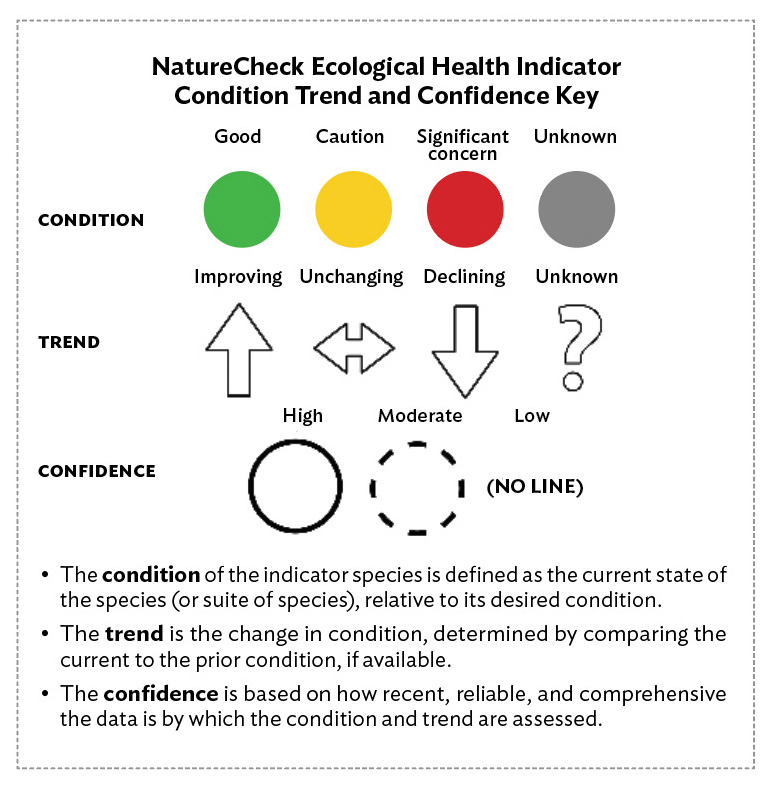

species condition: Good

Trend: unknown

Confidence: low

Susan Townsend marches up a golden hillside, grasses crunching beneath her camouflage snake gaiters. GPS in hand, she carefully locates a series of coordinates and marks each point with a bright orange flag. From holes in the ground, dark shapes scurry. Some stand up straight and let out a sharp chirp. Others flick their bushy tails, shoveling grass seeds into their cheeks at a fast-forward pace.

It’s a brisk, early May morning in Morgan Territory Regional Preserve, southeast of Mount Diablo. Townsend, a wildlife ecologist contracted by the network, is setting the boundaries of a survey site to count the California ground squirrel. After placing her markers, she sets up a field scope on an adjacent hill and begins clicking a tally counter as she scans the site. Part of a larger survey on ground squirrels at sentinel sites throughout network lands, Townsend’s work here will provide baseline data on population trends.

“[Ground squirrels are] widespread,” Townsend says. “But we still don’t have enough information on where they are exactly, and how their populations are doing.”

California ground squirrels are a common animal, easily spotted alongside trails throughout the East Bay. They build their burrows in grasslands, pastures, and oak woodlands, anywhere with soil loose enough to dig a burrow and with enough seeds, oats, and roots to support their diet. NatureCheck reports they live on 41 of 78 park or land units in network lands, but the population numbers and density of burrows are constantly in flux.

And ground squirrels don’t shy away from suburbs or farms, where they’re often seen as “troublesome rodent pests,” according to a report from the University of California’s agriculture extension program. Some ranchers see them as threats to roads, irrigation lines, and other infrastructure and often harass them with methods that range from aluminum phosphide burrow fumigation to baits laced with rodenticide. Fortunately, such control methods are not permitted on network lands.

While population trends are unknown throughout much of ground squirrels’ range, Townsend and other ecologists are steadfast that these mammals are far from pests. Squirrels, she says, are a keystone species—a central player in the vibrant, diverse East Bay grasslands.

California Tiger Salamander

(Ambystoma californiense)

species condition: GOOD

TREND: DECLINING

CONFIDENCE: MODERATE

Ground squirrel burrows are much more complex than they seem on the surface. “They’re ecosystem engineers,” Townsend says, and their labyrinth of burrows provides a moist, temperature-regulated home for a list of at least six other species, including a bizarre, charismatic amphibian called the California tiger salamander.

Named for the yellow spots and stripes down its slick black body, the California tiger salamander is large for an amphibian, up to 8.5 inches for males. Protruding eyes and yellow “lips” accentuate its wide, ceaseless grin. Tears of a clown, perhaps—this species historically ranged throughout the Sacramento and San Joaquin Valleys, but urban and agricultural development has extirpated it from half its range.

But in the East Bay, particularly in the Diablo Range, tiger salamanders have found a refuge via ground squirrels. At the onset of significant winter rains, tiger salamanders lay their eggs in either vernal pools or, often, livestock stock ponds. Larvae hatch and spend a few months in the pool before reaching metamorphosis and setting out for a burrow, where they spend most of their 10-year lives. They venture out only in the winter and early spring to breed.

The East Bay’s native amphibians have shown particular resilience to recent drought, and for the tiger salamander, these burrows are key. The presence of ground squirrels is in fact a metric for determining the presence of the tiger salamander. “We assume that California ground squirrels actually have to be there if tiger salamanders are going to be around,” says Tammy Lim, a wildlife ecologist for EBRPD.

Golden Eagle

(Aquila chrysaetos)

species condition: caution

trend: unchanging

confidence: high

But even as California ground squirrels help engineer the grounds below, they are just as important for the skies above—specifically, as a meal of choice for East Bay birds of prey like prairie falcons, white-tailed kites, northern harriers, and, most charismatic of all, the golden eagle.

“No other flying creature occupies so large a place in the pages of history, poetry, and romance,” declared Texan naturalist Roy Bedichek of the golden eagle, a raptor that, indeed, can be found in mythology and folklore all over the world. According to the Muwekma Ohlone, the original inhabitants of areas in the East Bay, the Eagle is considered a creator and protector. In one Muwekma creation story, as waters receded from the hills, Eagle ordered Coyote to investigate the dry land and raise up the human race.

The eagle’s stature matches its cultural reputation. One of the largest and most powerful raptors in North America, the golden eagle is capable of killing wild ungulates like fawns and small deer—though it more commonly takes smaller mammals like rabbits, prairie dogs, and ground squirrels.

The northern Diablo Range is home to one of the densest known breeding populations of golden eagles in the world, supported by the bounty of squirrels. In the late 1990s, UC Santa Cruz researchers looked at eagle nests near Altamont Pass and found that ground squirrels comprised 64 percent of prey biomass. Known as the Altamont Pass Wind Resource Area, this area is also a significant source of mortality for golden eagles. The raptors can likewise suffer from secondary exposure to rodenticides and lead poisoning from spent ammo in carcasses. Although lead ammunition for hunting has been banned in California, other states have not yet followed suit.

In other words, when we mess with the ground squirrel, we’re messing with a bird that is fully protected from killing or harassment by both the California Department of Fish and Wildlife and the federal Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act.

East Bay Stewardship Network Partners