There is a certain charge you get when you step over the boundary of a wilderness area, John Hart writes in the July issue of Bay Nature, a feeling that even though the scenery has not changed the mental condition has.

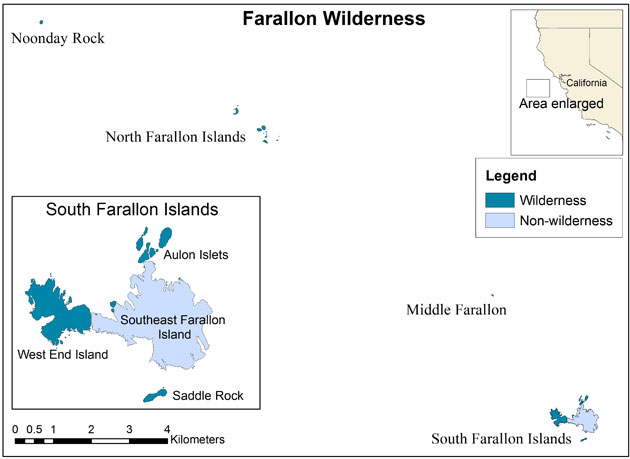

Imagine, then, the psychological jolt that accompanies a first step into the Farallones Wilderness, on the rocky islands 30 miles west of the Golden Gate. Only a handful of people take that step each year. The route travels by a zipline across a narrow channel from Southeastern Farallon, the only inhabited island in the 211-acre Farallon National Wildlife Refuge, to the uninhabited rock of Maintop Island, also called the West End. You edge past a sign, and clip into the zipline. A strong push gets you halfway across, and there you are, suspended on a stainless steel cable over jagged rocks and crashing surf, sea lions splashing below, birds screaming and wheeling above, inching along the tether that connects the pretty-damned-remote-but-human-inhabited Southeast Island to the Wilderness.

“When you cross that boundary,” says National Park Service wilderness planner Nyssa Landres, “you feel it.”

The Wilderness Act that preserves that spirit in parks across America turns 50 this September; shortly afterward, the Farallon Wilderness turns 40. United States Public Law 93-550, recorded on December 26, 1974, announced in two simple paragraphs that 141 acres around the island would hereafter be free of human occupation. (The next recorded law, 93-551, opened Little League baseball to girls.)

The designation of this wilderness was one of the easier wilderness decisions, Hart writes — because, well, no one had any designs on these remote and forbidding rocks. Landres, who spent about a month on Southeast Farallon in 2013 as a wilderness fellow assigned the task of describing the area’s “wilderness character,” agreed. Each wilderness area has its own unique essence, and the Farallones’ might just be how utterly, unbelievably wild they are. It is remote, otherworldly, and in an odd-but-intended sort of way, inhuman. Maybe the most famous of Wilderness Act’s definitions is that wilderness be “an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man.” The Farallon Wilderness, in Landres’s report, sports a “trammeling action scoring index” of zero.

“You really are a visitor who will not remain, who cannot remain without this expensive support system that’s been provided to you,” Landres says. “The islands are alive around you. It feels like you’re the alien in this environment.”

Jonathan Shore, the assistant refuge manager for the Farallones National Wildlife Refuge, says the word that comes to mind is “rugged.” It is rocky, foggy and windy, and rings with the ceaseless cry of birds. The sour smell of guano pervades the islands, forcing many a seasick traveler to the boat rails. Nature here is constantly flexing its muscle.

“For the Farallones, the main theme for wilderness is just leave it be,” Shore says.

The islands’ remote, difficult nature made the wilderness designation easy — but it has also made it successful. Point Blue Conservation Science researchers have continuously occupied Southeast Farallon Island since 1968, but even researchers rarely access the west, middle and northern islands in the refuge. The last documented onshore visit to an island in the wilderness other than West End was in 1994.

Under the protections of the National Wildlife Refuge, established in 1909, and subsequent wilderness protection, bird and pinniped populations have rebounded.

The northern fur seal, hunted in the 1800s around the Farallones from 180,000 animals to extirpation, returned to haul out in the wilderness area in 1974. In 1996, a northern fur seal pup was born on West End. Shore says the fur seals are now regulars; there were 213 pups in the wilderness in 2012. The seals, which are highly sensitive to human disturbance, still haven’t returned to the non-wilderness Southeast Farallon.

The common murre, meanwhile, whose population crashed from 1 million to about 6,000 because of egging in the Gold Rush era, has bounced back to around 150,000 breeding pairs.

And while the restoration stories are good news, so is the overall abundance of life of all kinds. There are more than 300,000 breeding seabirds, according to the Wildlife Refuge: ashy storm-petrels, Cassin’s auklets, pigeon guillemots, tufted puffins, the world’s largest nesting colony of Brandt’s cormorants and more than 9,000 breeding western gulls. There are five species of pinniped, including elephant seals and threatened Steller sea lions, which like the fur seals, breed only in the wilderness areas. The islands are alive with the sounds of non-human music.

“I think some of my favorite days were the foggy ones,” Landres says. “You wake up and you’re enshrouded in this thick fog, and you can just hear these animals in this place alive around you.”

Yet they are not alive with just non-human, non-threatening music. And the remote rocky islands are not entirely exempt from the debate about the role of human intervention in wilderness areas, particularly when it comes to reversing some of the harm caused by human activity prior to wilderness designation. Non-native house mice run amok on the Southern Farallones, causing problems for seabirds and particularly the rare ashy storm-petrel. (The mice don’t eat the petrels’ eggs, but nonnative burrowing owls attracted to the islands by the opportunity to prey on the abundant mice do.) So the Fish & Wildlife Service and its partners have considered ways to eliminate the mice — including in the wilderness area of West End. A draft environmental impact statement for the project was released last October; USFWS is now weighing the comments it received as it prepares a final EIS. Even in one of the most “wild” wildernesses in the country, 40 years after a federal wilderness designation regarded as a slum-dunk for preservation, resource managers face tough philosophical questions about people and nature: Is it appropriate for humans to intervene to tip the scales in the petrel’s favor by applying poison in a designated wilderness area? Does manipulation to correct our own previous errors make an area more or less wild?

“The goal is to as much as possible leave the wilderness areas alone and let them be wild,” says Doug Cordell, a public affairs officer with USFWS. “In this case what you have is a species introduced by man. The problems the mice are causing there were created by men. So what we’re looking at, and again, we haven’t made a decision, is, is there a way to eradicate those mice?”

To read more about the Bay Area’s other wilderness areas, see John Hart’s story in the July issue of Bay Nature magazine.