On January 22, 2011, at Bay Nature’s 10th anniversary gala, we presented our first Local Hero awards to three distinguished Bay Area citizens for outstanding lifetime achievement in the fields of environmental journalism (Harold Gilliam), environmental education (Dr. Doris Sloan), and conservation advocacy (Dr. Martin Griffin).

The following interview with Doris Sloan, recorded in October 2010, is the last in our series of conversations with our awardees. The interview with Harold Gilliam appeared in the January-March 2011 issue; the interview with Marty Griffin appeared in the April-June 2011 issue.

For anyone curious about local ecosystems, it makes a lot of sense to start from the ground up. That means coming to terms with geology, which lots of folks find extremely daunting. And few places in the world have geology as challenging–and as active–as the Bay Area. So it is extremely fortunate for us that Doris Sloan, at the age of 40, decided to take a summer field class in the Sierra Nevada and thereby change the course of her life, and that of many others as well.

Her rare combination of expertise, enthusiasm, and clarity makes Doris an ideal guide into the complex realm of California geology. After 20 years of teaching at UC Berkeley and UC Extension, Doris capped her career by writing the “bible” for laypeople hoping to comprehend Bay Area geology: Geology of the San Francisco Bay Region (UC Press, 2006).

Doris has done more than just teach local geology. As an activist, she helped keep a nuclear power plant off Bodega Head. As a teacher, she enlisted her students to do research that helped keep major sprawl off the shore of San Pablo Bay. And she remains active as a board member for Citizens for East Shore Parks, a field trip leader for Cal Discoveries, and sage adviser on all things geologic for Bay Nature.

- Sloan’s father was a biologist at Washington University in St. Louis. Sloan (child at center) often went into the field with him in search of salamander eggs and other specimens. Photo courtesy Doris Sloan.

DL: Where did you grow up?

DS: I was born in Germany, but I grew up in St. Louis and lived there until I went off to college. And rarely went back because of its atrocious climate!

DL: What was your experience of nature while you were growing up there?

DS: My father was a biologist, and we lived near Washington University, where he taught, but just five minutes away there was still country in those days, in the 1930s and ’40s. And we would go out every spring to ponds in the glorious hardwood forests of rural Missouri where he would collect salamander eggs for his embryology classes and take these great jellylike masses back to the lab. And I remember–just talking about it brings back this fragrance of the wet leaves–tromping around looking for salamander eggs and because I was little and close to the ground, I got the pleasure of finding a lot of the eggs. So I grew up with biology and with the out-of-doors and thinking I would be a biologist when I grew up.

But we also did a lot of trips across the country. And my father had done a minor in geology, so as we’re traveling he’s saying, “Oh, look at that,” and talking about glacial deposits from the Ice Age and about mountain-building in the Rockies.

And the other key influence, which I’m just now remembering, is that we had a map of the world in our dining room, and I sat facing it from my place at the table. So at all the meals, I sat there looking at the world. And it got me thinking about geography and other countries and probably influenced me more than I know. I remember cleaning it very carefully with an eraser and looking at all these strange places and thinking, wouldn’t it be nice to see them someday? Never, of course, dreaming that I would!

DL: What brought you first to the Bay Area?

DS: I came after I met the man I was going to marry, toward the end of college. After I graduated from Washington University in 1952, we drove from Missouri in a Model A Ford, camping our way across the country. I had been camping only once with my family, and I loved it. I remember so vividly camping someplace in New Mexico or Arizona, and I can still hear the coyotes and remember lying there and looking at the stars. I discovered how much I adore living outdoors and was, and still am, happier living outdoors than anywhere I’ve ever lived. Love my house, love Berkeley, love the Bay Area, but when I go out and set up my tent, wherever it is, I’m more myself.

DL: Was part of your attraction to the region about the natural landscapes here, even though you weren’t yet doing geology?

DS: Oh, it was, because this is a marvelous place to live. When we lived in Sonoma County, we were always at the beach or in the redwoods. I drove up the coast last Sunday and remembered each of those beaches we visited. With the redwoods half an hour to the north, the ocean half an hour to the west, the Sierra three hours to the east, what more could you possibly want? Since I first came here in ’53 I’ve never wanted to live anywhere else.

DL: So when did you first start getting interested in geology? Was it love at first sight or a long courtship?

DS: I think it falls into the love at first sight category. In ’65, I got a job working for the Friends Committee on Legislation, which is a Quaker lobbying group. The office was in the basement and it had one of those window wells where you see a little piece of sky. I’d been working very hard in this basement for five years, looking at that little patch of sky, leaving Berkeley in the fog, going home in the fog, and thirsting for a little more outdoors. A basement office is the antithesis of working outside!

Then the summer my father turned 70, we arranged a family reunion near Port Angeles in Washington. From there we drove up to Hurricane Ridge in the Olympics. It was July–glorious wildflowers, and he knew them all. And also started to share all the geology he knew, which turned out to be quite a lot, and it was fascinating. Especially for somebody thirsting for more than a little strip of sky. And I thought, “Boy, I’ve got to get out more.” When I got back home I checked out the UC Extension catalog and found a weeklong High Sierra course in August in the Emigrant Wilderness, taught by [UC geologist] Clyde Wahrhaftig.

So I signed up, not knowing what to expect. If there hadn’t been room, the course of my life would probably have been very different. We camped at Maxwell Lake, and each day we went out in a different direction on foot. It was fabulous because we got introduced to different kinds of granitics, the landscape, the glaciers. And it was marvelous fun.

I came out thinking, “If I could do anything I wanted in the world, I’d go back to school, become a geologist, and lead trips like this.” And so the next summer, I signed up and took the class again. And I intended to ask Clyde to write me a letter of reference for Cal. Because I thought, I really just want to spend a year learning some geology, and then go back to my basement office a happier camper.

Well, I not only had a marvelous time, but I found I loved sharing what I’d learned the previous summer; I discovered that I loved to teach. I sort of became Clyde’s assistant because he had 30 people asking him questions, and I started answering the ones that I could. Then at the end of that wonderful week, I went over to Clyde’s campsite with a bottle of brandy I had brought along and said, “How about a little brandy?” And I told him that I’d really like to go back to school.

What I didn’t know at the time–but very quickly learned–was how male-dominated geology was. The department at Cal had no women faculty and very few women grad students. I knew Clyde wasn’t very keen on women in the field, but I didn’t know how typical this was.

So I asked him to write a letter so I could go back to school and learn a little geology. He asked, “What do you want to do with it?” And I said, “Oh, all I want to do is get a job with California Division of Mines and Geology and work behind the information counter.” And he said, “Oh, well, that’s all right then.” And wrote the letter.

So I went in with my letter to the chair of this department that’s not interested in having women students or faculty, and he leans back in his chair and says, “Tell me, Doris, are you really interested in geology or are you just after Clyde?”

DL: Whoa!

DS: He didn’t know–but I did–that Clyde was gay! Clyde didn’t come out for a couple more years. I turned beet red and blubbered something. I didn’t know that the dean had been hassling him about not having women students, and here I was, a middle-aged woman, clearly not with high academic intent, you know, and so I was perfectly safe, and I got in! I worked part-time in my basement office and started taking classes.

I really intended just to do my one year and go back to working full-time. But at the end of that first year Dick Hay, one of the few faculty members who encouraged women students, asked me if I would be head TA for the introductory class and run the labs. I was flabbergasted. They were going to pay me to have fun! I debated whether to go back to lobbying, but I’d done that for eight years, and you get kind of burned out, especially on social issues where you don’t win many. So I said OK, and the rest is history. I think it qualifies as love at first sight.

DL: But not necessarily with Clyde!

DS: No, not with Clyde! [Laughs] He and I became very good friends though.

DL: Do you consider him one of your geology mentors?

DS: He was one of two key mentors; the other was Garniss Curtis. Clyde and Garniss taught me to look at the landscape and to ask why is it the way it is. That’s the really fun part of geology. It’s a living mystery story. You go out and you think, “Why is that rock that color? Why is it shaped that way? Why is the water here and not there?” Last Sunday I was driving from Berkeley to Kehoe Beach out at Point Reyes, and you go through 12 or 13 different ecological habitats. It’s just amazing: the Bay marshes, the Bay itself, oak woodland, riparian, redwood forest, beach cliffs, sand dunes, and more. There’s one place along Lucas Valley Road where you go over the hill by the big rock where you’re in serpentinite barrens, but then at the bottom of the hill you’re in contact with the graywacke–a locally common sandstone–and the vegetation totally changes. And so you look at the vegetation, and you say, “Now why is it oak right here and redwood forest there?” That’s what Clyde and Garniss taught me.

DL: Were you in school at the time when plate tectonics was beginning to be understood?

DS: No. That big shift came right before, in the mid to late ’60s. I went back to school in the fall of ’71. But it was an incredibly exciting time to be getting into geology because everything was being looked at in a new way, and California began to make sense. Until that time geology was a descriptive field: You described what you saw, but the big picture wasn’t clear. And then all that began to fall into place. I remember long discussions about our Franciscan rocks–the graywacke, the chert, the basalt. How could they be here? We thought graywacke had to have come down from the Sierra Nevada, but the grains in the rock didn’t fit the Sierra, so what’s going on? We didn’t realize they’d come from somewhere else, brought here by plate movements from deep in the ocean.

DL: Is it plate tectonics that makes the geology of this area both so difficult and so fascinating?

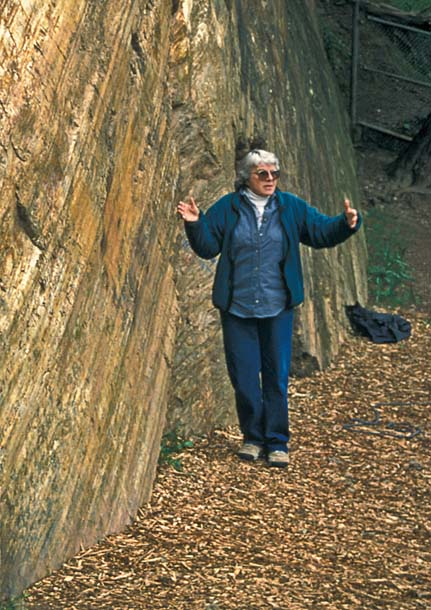

- At San Francisco’s Corona Heights, Sloan shows her students a remarkable exposure of chert with slickensides, where the surface has been polished smooth due to the tectonic grinding of rock against rock. Photo by John Karachewski, geoscapesphotography.com.

DS: Yes, that and time. One of the big challenges in looking geologically at the landscape is to think in two time scales–you’ve heard me say this many times. First you think back on what was going on in the world when the rocks themselves–the bedrock–were formed; and then you think about the processes that shaped the present landscape. And the fascination is seeing this variety, looking at the Franciscan bedrock, seeing that much of it is deep ocean deposits–basalt, chert, graywacke–plus the serpentinite. What was the world like when they were formed, 100 to 200 million years ago? How did they come from the deep ocean, underwater and thousands of miles away? And how do you explain the way you find them today?

Faulting has rearranged those rocks so that you have Marin Headlands rocks–part of the Marin Headlands terrane–on top of Mount Diablo! And you have another chunk of it down in the Coyote Hills. But it’s all clearly from one block that has been cut up by faults and moved around.

That leads you to the present-day landscape–shaped in the last million years or so, broadly speaking. Why do all our ridges trend northwest-southeast? Why is the Bay there? To most people a million years is very old and almost inconceivable. And as you’ve probably heard me say, one of the things that makes you feel like a geologist is when a million years starts feeling young. We’re so used to thinking of mountains as forever, “rock of ages” and that kind of thing, that it’s not easy for people to realize that the Berkeley hills are very young, only a million years old. And they’re still going up!

DL: Are there any major local geologic puzzles still waiting to be solved?

DS: Oh yes, many. One of my favorite mysteries is how the Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers found their way out through Carquinez Strait. I’ve been puzzling about it for 20 years and keep hoping I can find a grad student who’ll take it on. I was up at Mare Island 10 days ago, puzzling again about the Napa River. Maybe the Sacramento and San Joaquin didn’t flow through Carquinez at the beginning but looped around and carved that big valley of the lower Napa River, which is far too big for this little Napa River to have cut.

DL: So the story I learned of the rivers in the Central Valley first draining out to the south and then, when that got blocked, cutting through Carquinez half a million years ago, that’s speculation?

DS: No. The rivers did cut a channel through the inner Coast Ranges as they were going up. The idea of a Lake Clyde (named after Clyde Wahrhaftig) that filled the Central Valley when the southern outlet got blocked by movement along the San Andreas Fault–that’s solid. And the water backed up and either spilled over as Lake Clyde breached the relatively low inner Coast Ranges–like overtopping a dam–and/or cut a channel through them as they were going up. The only thing that’s speculation is whether it cut Carquinez Strait at the same time as it started overflowing, or whether it first flowed north through what’s now the Grizzly Island-Suisun marshes and across to the present Napa River and formed the river’s broad mouth at San Pablo Bay.

DL: How did you begin teaching?

DS: I received my master’s in 1975 and the only geology jobs then were with oil companies, and I’m not a corporate type. But then Clyde walked in as I was trying to figure out what to do and rescued me by offering me a job teaching environmental science.

DL: Can you describe the program?

DS: It was a fabulous environmental sciences undergraduate major. I had no bosses except a dean and I could more or less do anything I wanted. And I turned it into a sort of mini-master’s research program.

Environmental sciences was the ideal thing to teach–after geology. I would have loved to teach geology–but environmental sciences in some ways was even more fun because it was so new. Think of the environmental laws that were new in the early ’70s and all the environmental agencies that were being formed. By the time EPA offices were being set up, I had the first round of environmental science graduates and they got jobs all over the West in those first EPA offices.

We had three tracks the students could take: biological, physical, and social. And they all came together as seniors to do a research project on a topic we picked together. So, for example, one year we studied water in Berkeley, another we did seismic safety, and another San Pablo Bay. The students did background reading, designed a research protocol, collected the data in the field or in the lab, and then wrote it up. It was very rigorous. I was a tough taskmaster.

DL: And the Bay Area was your classroom.

DS: Yes, exactly. And we made some real contributions in the ’70s and ’80s. For instance, in 1980, we did our project on San Pablo Bay, including the proposal to develop the Cullinan Ranch diked wetlands property along the northern bayshore, west of Mare Island, into a community of 1,500 houses. The developers were going to have to bring sewage and power lines across from Vallejo, under the Napa River. If Cullinan Ranch were developed, the whole San Pablo Bay shoreline between the Petaluma and Napa rivers would look like the shoreline of the Peninsula–you know, Foster City North. So I got involved with Save the Bay in a campaign to protect the wetlands. The state agencies really didn’t have the resources to do the background research. So the students did vegetation and bird surveys, all kinds of biological assessments that the agencies could use as part of their database. And eventually the Japanese developer pulled out and the wetlands were saved.

DL: How does it feel that Cullinan Ranch is now, finally, being restored?

DS: Every time I fly over it I look down on all that green and all that water, and I think, “That was great!” I’ve had the blessing of being part of several huge environmental victories. The first one was being part of the team that kept the nuclear power plant off of Bodega Head in the late ’50s and early ’60s. And then Cullinan Ranch. And then–and still–with Eastshore State Park, where Citizens for East Shore Parks and others have been successful in protecting the Bay shoreline from Oakland to Richmond. And I look back on those victories and my teaching career, and my fun in geology, as the highlights of an absolutely marvelous 40 years.

.jpg)