Heading out from the Richmond harbor to Brooks Island in the launch Iri Queen last winter, we paralleled the sandspit that has built up along a two-mile man-made breakwater. East Bay Regional Park District supervisor Kevin Takei pointed out the beach near the base of the spit that would swarm with Caspian terns in a few months, when the seabirds returned from their wintering grounds in Southern California, Mexico, and Guatemala.

Past the colony site, on the 45-acre natural part of the island, we moored at a rickety floating dock below the caretaker’s residence. Although access is usually limited, Takei had arranged a ride for us with a park district maintenance crew.

After the park staffers got to work, Takei took us on a quick circumambulation. The trail led up through a mini-forest of coyote brush and remnant patches of native grassland, past outcrops of lichen-mantled chert. From Jefferds Peak, the 160-foot-high summit, a magnificent view opened: east to Mount Diablo, west to the Golden Gate. The silence was profound. I recalled what Supervising Naturalist Dave Zuckermann had told me earlier: “Here you are in the middle of a huge metropolis. You get out to the island and it’s like you’ve stepped back in time a hundred years or more.”

Returning to the dock, we skirted the permanent spring that provides water for the island’s resident caretakers and got a look at Bird Rock, across a shallow channel, where a couple of harbor seals had hauled out. It was hard to believe we were just a mile from the busy Richmond waterfront. Brooks Island has the feel of a place apart.

Brooks, a regional preserve, is a relict slice of coastal habitat, home to uncommon plant and insect communities and the Bay’s largest Caspian tern nesting colony. The island may even play a role in a complex federal attempt to balance the needs of the terns against those of endangered salmon from the Columbia River to the South Bay.

Although the terns are recent arrivals here, other island fauna and flora have roots going back to the Pleistocene, before the island was an island, and the human presence on Brooks spans millennia. Former Contra Costa College instructor George Coles, who excavated the island’s primary shellmound in the 1960s, says the oldest carbon-14 dates he obtained were around 1,700 to 2,000 years before the present. He suspects the site goes back at least 3,000 years, and says, “Odds are the inhabitants were Ohlone.”

UC archaeologist Nels Nelson sampled the site in 1907, but Coles did the first systematic study. Among the volunteers on his dig were East Bay conservation icons Will and Jean Siri. Jean Siri served many years on the park district board, and Coles recalls her as a driving force behind the island’s addition to the East Bay Regional Park system.

The Brooks shellmound yielded the remains of cormorants, ducks, and other waterbirds (although no pelicans), as well as harbor seals, sea lions, porpoises, and whales. The inhabitants hunted with atlatls and bone-pointed harpoons. They took fish, particularly herring, in quantity, perhaps using nets–Coles didn’t find any hooks in the mound. Mollusks–mussels, oysters, clams–were the mainstay.

- Since about 1980, Caspian terns like these have nested on the man-made sandspit that stretches for almost two miles from the north side of the island. Photo by Ken Collis, www.birdresearchnw.org.

The archaeological record suggests a stable, sustainable way of life, though it’s not clear if people lived on the island for long periods at a stretch or simply visited seasonally. UC Berkeley archaeologist Kent Lightfoot is reanalyzing Coles’s material for seasonal patterns. In either case, Brooks Island may have been used until European contact, although the most recent carbon-14 date obtained is about 300 years ago.

- A Caspian tern flies over Brooks Island, returning with a Pacific herring for its offspring. The terns hunt mostly in the waters near the Golden Gate Bridge but also make forays into San Pablo Bay. Photo by Daniel Roby, www.birdresearchnw.org.

Eighteenth-century Spanish records don’t mention inhabitants. Juan Manuel de Ayala, on the first nautical survey of the Bay in 1775, named the island Isla de Carmen, but by 1850 charts were referring to it as Brooks Island. We still don’t know who the eponymous Brooks was. The name became official on the state legislature’s definitive map of California in 1853.

Sheep Island was an alternative name. Luccas Gargurevich, a Croatian immigrant who settled on the island in 1870, later told his son Anton, “The man on Goat Island [Yerba Buena] raised sheep, and I raised goats, so I have named it Sheep Island.” A good story, but “Sheep Island” appears on an 1856 map.

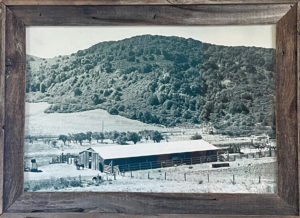

Gargurevich brought his bride Dominica to the island in 1880. Nine of their children were born there. The patriarch equipped a schoolroom and hired a teacher who came out from Oakland during the week. When Dominica died in childbirth, Luccas lost heart and moved the family to the mainland. All they’ve left behind is a stretch of stone wall.

Then the quarriers went after Brooks’s graywacke sandstone. The most destructive period began in 1918. Extensive operations, some using San Quentin chain gangs, scarred the island’s southern side. Brooks Island rock went into San Quentin’s south cell block, the foundations of Treasure Island, and the Bay Bridge Toll Plaza. Now filled with water and cattails, the excavations attract nesting red-winged blackbirds.

Meanwhile, developers floated a string of schemes for the island. The Central Pacific Railroad proposed a freight terminal there in the 1870s. During the First World War, the U.S. Navy considered leveling the island (as well as Albany Hill) to build a battleship dock, but the site lost out to Hunters Point. The City of Richmond had its own grandiose dreams in the 1950s, involving a causeway from Point Isabel and a heliport. A developer named Ben Gerwick wanted to flatten the hill and sell commercial and industrial lots in 1962.

By the mid-sixties the Sheep Island Gun Club took over. Organized by entertainer Bing Crosby and restaurateur “Trader Vic” Bergeron, the club leased land, hired caretakers, and stocked the place with exotic game birds: pheasants, chukar, bobwhite quail. Even after the park district bought the island in 1968, the gun club and its caretakers stayed on until Brooks was ready for public access in 1988.

- Oregon State University researchers use this blind to observe the colony, documenting nesting success and interactions between terns and other birds. Photo by Ken Collis, www.birdresearchnw.org.

Island ecology has fascinated naturalists and biologists from Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace to E. O. Wilson. Every island is an experiment–start with an initial complement of species and let time, chance, and natural selection shuffle the deck. Sometimes humans introduce a wild card, and Brooks has been dealt several of these.

- Researcher Lindsay Adrean releases a banded tern. Photo by Tim Marcella, www.birdresearchnw.org.

Brooks Island preserves plant communities that have become rare on the East Bay mainland. Native grassland, with such species as purple needlegrass, persists there; exotic Mediterranean grasses have never taken hold. The island is one of the few East Bay locations for the seaside woolly sunflower. Trees are sparse: a few California buckeyes, red and arroyo willows, and blue elderberries, plus exotics like Monterey cypress, planted by settlers and caretakers.

The native plants provide rich habitat and food for insects. When UC Berkeley entomologist Jerry Powell surveyed Brooks Island’s moths and butterflies in the 1990s, he found that 10 percent of the species were either unknown in the San Francisco Bay region or unrecorded for 50 to 100 years. Many were small and obscure, but Powell documented showy species like the Mexican tiger moth, not previously thought to occur in the Bay Area.

During the Ice Age, Brooks Island was a hill–part of the same Franciscan bedrock as Albany Hill and the Coyote Hills–in the broad valley that would become San Francisco Bay. When sea level rose, its populations of salamanders and western terrestrial garter snakes were marooned. They’re still out there, links in a simple snake-eat-salamander food chain.

Brooks Island had no land mammals until house mice and brown rats colonized it in the post-contact era. Another wild card came when biologist P. K. Anderson translocated seven California voles from Orinda to Bird Island, a barren rock on the west side of Brooks, for research in 1957. At some low tide, they skittered across the mudflats to Brooks Island. By 1959 they had spread over the larger island and were beginning to breed. Stressed by the competition, the house mice failed to reproduce and dwindled to extinction. The voles, despite the depredations of the garter snakes and visiting raptors, are still going strong. A unique mutation gives some a lighter, buffy coat distinct from their mainland relatives’.

- Though the summit of the island tops out at 160 feet, the sandspit (left side of the panorama) is barely above the waterline. Sandy or rocky areas bare of vegetation are the terns’ preferred nesting habitat, but the colony seems to be decreasing, caught between erosion from the Bay and encroaching invasive vegetation. Photo by Kira Stoll.

Although the exotic pheasants and partridges have died out, native birds remain. Black oystercatchers nest along the shoreline, black-crowned night herons occupy the buckeyes, and harlequin ducks have been observed year-round. Two years ago, three pairs of black skimmers, newcomers to the Bay, attempted to nest. Brooks also holds a dubious distinction as the first local nesting site for Canada geese, beginning in 1959.

But the bird in the conservation spotlight is the Caspian tern. The largest North American tern, this gull-size seabird has a dagger-shaped orange-red bill, a shaggy black crest, and a raucous voice. Although it breeds throughout the Northern Hemisphere, the tern didn’t show up in San Francisco Bay until 1922, when a few nested on levees in the South Bay. Around 1980, the terns discovered Brooks and began to nest in an unvegetated spot at the base of the long sandy spit. The site now hosts the region’s largest colony.

- Trail to the summit. Photo by James A. Martin, www.islandsofSFbay.com.

Oregon State University biologist Daniel Roby and his graduate students have been monitoring the Brooks Island colony since 2003. Part of their project involves five-gram transmitters that track terns’ foraging trips. Results so far indicate the birds do most of their fishing near the Golden Gate Bridge; some commute to the east side of San Pablo Bay, and a few fish in East Bay reservoirs.

Researchers also watch the terns from a blind on the spit. Following up on previous park district observations, the Oregon State team monitors productivity (0.42 chicks per nest last year, which Roby considers “fair to middling”), records interactions between the terns and their neighbors, and tallies the fish they bring to their mates and nestlings. That last part sounds daunting, but graduate student Lindsay Adrian says it can be done, with training: “Most we can identify to species, some only to family.”

“The colony is decreasing,” says District Ecological Services Coordinator Steve Bobzien. On the spit, erosion is outpacing deposition and the colony site is washing away; tern nests have been flooded by high tides. Rising sea levels aren’t likely to help. Vegetation–exotic ice plant and marguerite daisies– has grown into the nesting site from the land side. The district has been removing the plants by hand, taking care not to worsen the erosion.

“The terns are sandwiched between the eroding shoreline and encroaching vegetation,” Roby says. They’re also hammered by California gulls, whose numbers on the island have exploded over the last five years: “They compete with the terns for nesting sites, steal fish from them, take their eggs, even chicks if they’re small enough.” The district has not resorted to lethal gull control here, unlike at Hayward Regional Shoreline, where an endangered species is at risk [see sidebar “Hayward Haven,” part of this issue].

- View from the island, looking northwest to the long sandspit. Terns aren’t the only birds that nest on Brooks Island, which has some claim to infamy as the Bay Area’s first recorded nesting site of Canada geese. Brooks, sometimes called Sheep Island, was also long used by the Sheep Island Hunting Club, which counted Bing Crosby among its members. Photo by James A. Martin, www.islandsofSFbay.com.

Developments far to the north made Brooks Island part of a sweeping wildlife management plan. Caspian terns nesting at the mouth of the Columbia River take a heavy toll on young salmon and steelhead, both federally listed species. Since the birds require open ground for nesting, federal agencies agreed to disperse the Columbia colony by letting their nest site revegetate. The hope was that the displaced terns would relocate to alternative sites where nesting habitat had been created or enhanced. Brooks Island was chosen as one such site, along with Hayward Regional Shoreline, Don Edwards National Wildlife Refuge, and locations in Oregon. Initial plans called for controlling vegetation and adding sand or gravel for nesting substrate.

But the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration now has reservations about Brooks. The National Marine Fisheries Service recommended that its partners, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, take on the two other Bay Area sites first. Tern habitat would be enhanced at Brooks only if the terns don’t adopt the Hayward and Don Edwards sites within three years. Army Corps fisheries biologist Allison Bremner says her agency is treating that as a directive. No comment could be obtained from Fish and Wildlife.

The problem at Brooks appears to be that the terns here are also hunting endangered salmon and steelhead. Preliminary data from Roby’s fish-spotters shows salmon smolts making up almost 9 percent of the terns’ diets in 2008. Sifting the sands for tiny coded wire tags that are injected into the skulls of hatchery fish, Roby has determined that many of the salmon the terns are taking are fall-run chinook released in San Pablo Bay. “The whole reason the Caspian tern management plan was put in place was to try to restore Columbia Basin salmonids,” says Roby. “Moving the problem [to San Francisco Bay] is not what anyone wants to do.”

The California Department of Fish and Game released over 20 million chinook smolts last spring and only a small percentage may be falling prey to the terns, but Bobzien says, “Fish would definitely take precedence over restoring Caspians on that island, since there are other nest sites.” A Fish and Game spokesperson acknowledges concern over any predation, but says more analysis is needed.

Whether or not the terns stay, Brooks Island endures. Fred McCollum, a onetime Brooks Island caretaker and vole researcher, used to say the most remarkable thing about the island was that it was still there at all. Brooks has survived goats and quarrymen, the machinations of robber barons, and the strategic dreams of the navy. And much of it would still look like home to the Ohlone.

Naturalist-led park district tours offer access to the island from March to October. You can bring your own kayak, use one provided by an outfitter, or catch the April voyage of the fishing boat Delphinus. Visit www.ebparks.org/parks/brooks_island for details.

.jpg)