Ellen White was exhausted after her cross-country travels from Washington, D.C., to Napa County. While passing through the Sierra Nevada mountains, White, a founder of the Seventh-day Adventist Church, developed altitude sickness, and her companions feared she might not survive the journey home. When she did finally arrive in St. Helena, there was a message urging her to visit a new location for an Adventist four-year college. They’d been looking for an area away from the city life in Healdsburg, where the school was currently located. Despite her weakened state, the next morning White rode in a coach six miles to Howell Mountain to survey the property.

It was September 10, 1909, and the land for sale on Howell Mountain, part of the coast range that includes Mount St. Helena and creates the eastern flank of the Napa Valley, supported the headwaters of Moore Creek and mixed forests of pine, Douglas fir, oak, and even coast redwood. White noted its good farmland, ample timber species, mature fruit trees, and buildings from an existing health spa that could host the students as they built the college. “I wondered how we could have found another site that would better suit our needs than the one we have found here,” White later wrote, “[a] place where we can study the works of nature, and in the woods and mountains around us, learn of God through His works.”

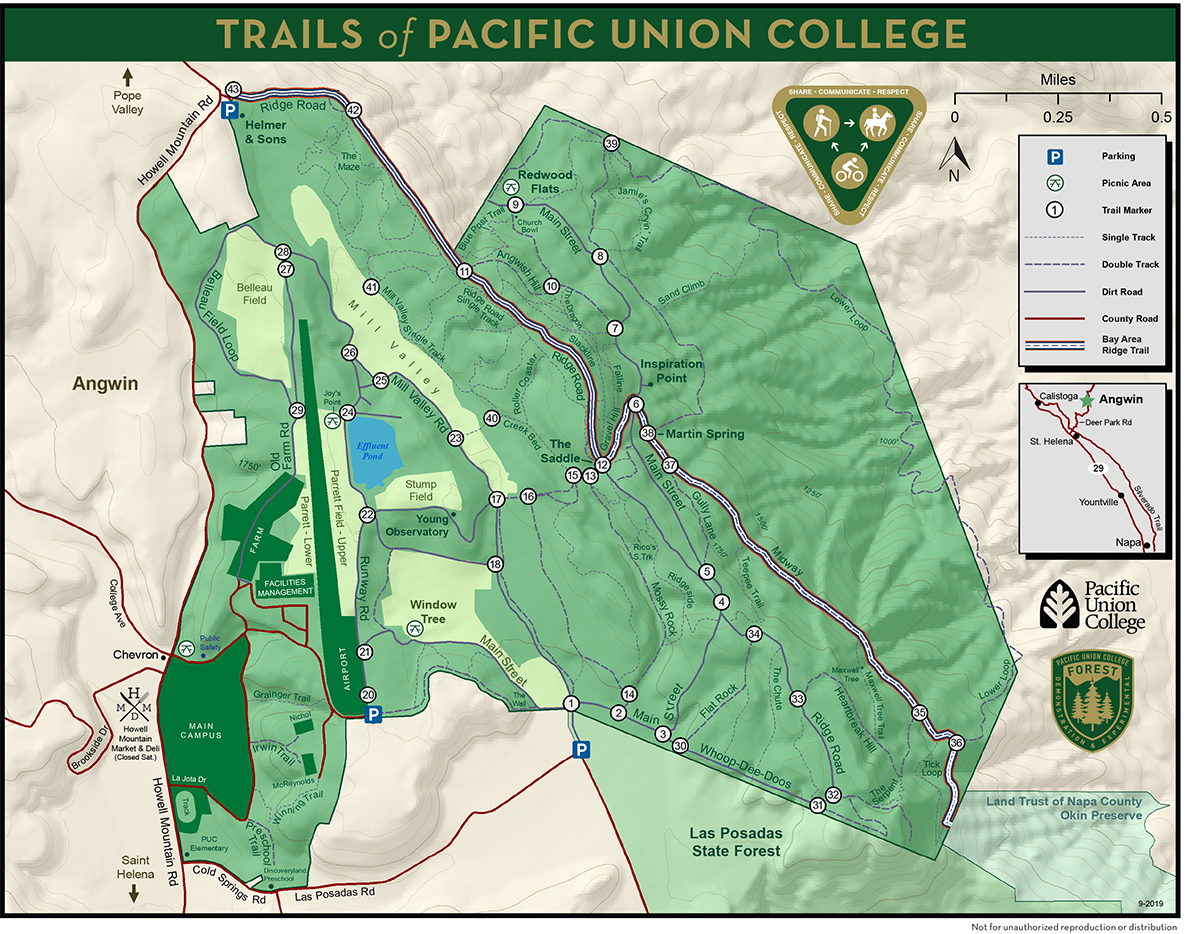

One hundred and ten years later, for the first time since White moved her school, Pacific Union College is inviting the public to explore its 35 miles of recreation trails through its 864 acres of ecologically unique forest—home to endemic plants essential for survival of our state insect, California’s most inland coast redwoods, and complex geology. In October, I met Peter Lecourt, PUC’s forest manager, for a walk through the property. Tall, gregarious, born and raised in the college’s tiny town of Angwin, Lecourt hadn’t walked us to the forest entrance before someone called out his name and stopped to chat. Nearly everyone we met during our hike seemed to know him.

We set out for a vista on the east side of the forest called Inspiration Point. To get there we first hiked to the ridgeline, which extends north into the Mayacamas Mountains and south to Benicia. Wildlife, including big predators like mountain lions and black bears, travel this long corridor, which is one reason the Land Trust of Napa County had long been interested in seeing the PUC forest area protected.

Remember, they are an exotic species in the Western United States, and are rapidly increasing their geographic range and range of habitats. Are they outcompeting or excluding native species in the process? How would we know? We have done almost nothing to monitor changes in the assemblage of mushroom species in areas before and and after the incursion of death caps.

Further Reading

Pringle et al, “The ectomycorrhizal fungus Amanita phalloides was introduced and is expanding its range on the west coast of North America,” Molecular Biology 2009

Lockhart et al, “Simultaneous emergence of multidrug-resistant Candida auris on 3 continents confirmed by whole-genome sequencing and epidemiological analyses,” Clinical Infectious Diseases 2017

Battalani et al, “Aflatoxin B1 contamination in maize in Europe increases due to climate change,” Scientific Reports 2016

Explore the PUC Demonstration Experimental Forest

»Parking & facilities

For now, roadside parking is allowed on the shoulder of Las Posadas Road. There are no bathroom facilities nor potable water. Future plans include a 30-car parking lot, picnic tables, drinking water, and a portable toilet adjacent to the entrance by 2021.

»Entrance & trails

The forest’s current entrance is just to the north of Las Posadas State Forest signs. Head north to Trail Marker 1. These newly installed markers throughout the forest correspond to the PUC trail map, which can be downloaded at puc.edu/forest. Hiking, mountain biking, horseback riding, and dogs on leash are permitted.

“It’s an important corridor in Napa County,” explains Doug Parker, executive director of the Land Trust. “The biggest gap in the northern part of the corridor is in Angwin.” The PUC forest land lies directly between Las Posadas State Forest and Dunn-Wildlake Preserve. Parker also stresses the property’s high biodiversity and important species, like northern spotted owls, and the fact that Moore Creek, which flows south through the forest, feeds Lake Hennessey, the water supply for the city of Napa. The property also sits on prime vineyard land and has been considered at high risk for development.

For a number of years, the school sought to sell the land to build an endowment to support its mission. But when John Henshaw, a former Land Trust board member and retired USFS forester, “came and talked to us about a conservation easement, that’s when we really realized the land is our endowment,” Lecourt says. “We need to make the land support the mission of the school in ways other than selling it.”

In December 2018, Pacific Union College, the Land Trust, and Cal Fire finalized a conservation easement, through the state’s Forest Legacy Program, that prevents development or agricultural activity on the forest land—rights the college gave up in exchange for $7.1 million from the state and donors—but allows the college to retain ownership of the property.

Working under the guidance of Henshaw, Lecourt’s position was created just two years ago. For the school to invite the public onto its lands and cover the associated liability, it signed a trail license agreement with Napa County Regional Park and Open Space District this past summer. The forest’s network of trails has been a local secret for decades; now, a new trail map and markers signal the beginning of another era.

Lecourt is overflowing with ideas and plans for the forest. The trail we’re standing on was recently dubbed a 2.9-mile addition to the Bay Area Ridge Trail, the 550 miles of proposed trail circumnavigating the ridges around San Francisco Bay. Fundraising for parking and facilities is in motion. Fuels reduction work is underway in the forest; its last fire was in 1931. Lecourt hopes for more forestry research, planned outings, a $2 million endowment to support the forest’s stewardship, and more.

After about a mile of strolling through a mix of towering Pacific madrone, ponderosa pine, and Douglas fir, we reach Inspiration Point, a rock outcropping where the side of the mountain quickly falls away, creating an opening in the forest wall and a view east of a series of valleys and ridges. Closest is Chiles Valley, followed by Pope Valley, and then the wide gulf holding Lake Berryessa, all framed by the gold leaves of old black oak trees.

“I remember as a very small child coming out here when it was pouring rain and splashing around in puddles and riding bikes,” Lecourt says. “Some of my earliest memories of growing up in Angwin are from coming out here with my dad.”

As a kid he bushwhacked through the forest. Later as a teenager he road mountain bikes through it. “I couldn’t get lost in here if I tried,” he says, gesturing behind him.

As we walked down the mountain’s east side, heading toward an area called Redwood Flats, we came across our first Napa false indigo, a shrub with wine-colored and richly scented flowers that’s endemic to Napa and its neighboring counties; the California Native Plant Society considers it rare and fairly endangered. Which makes it all the more interesting that California’s state insect—the dogface butterfly—depends on the indigo as a host. It’s the only plant the caterpillar feeds on before metamorphosis. Named for the poodle-like profile on the male’s wings, the dogface became our state insect in 1972. These days it’s an uncommon butterfly to encounter and the “life-history is not well understood,” writes UC Davis entomologist Art Shapiro.

Perhaps surprisingly, then, there appears to be an unusual number of the shrubs growing in the PUC forest. Botanist Jake Ruygt, who has surveyed the forest, says that the abundance of Napa false indigo “stood out as exceptional,” speculating that they prefer the volcanic soil found in the PUC forest and surrounding area.

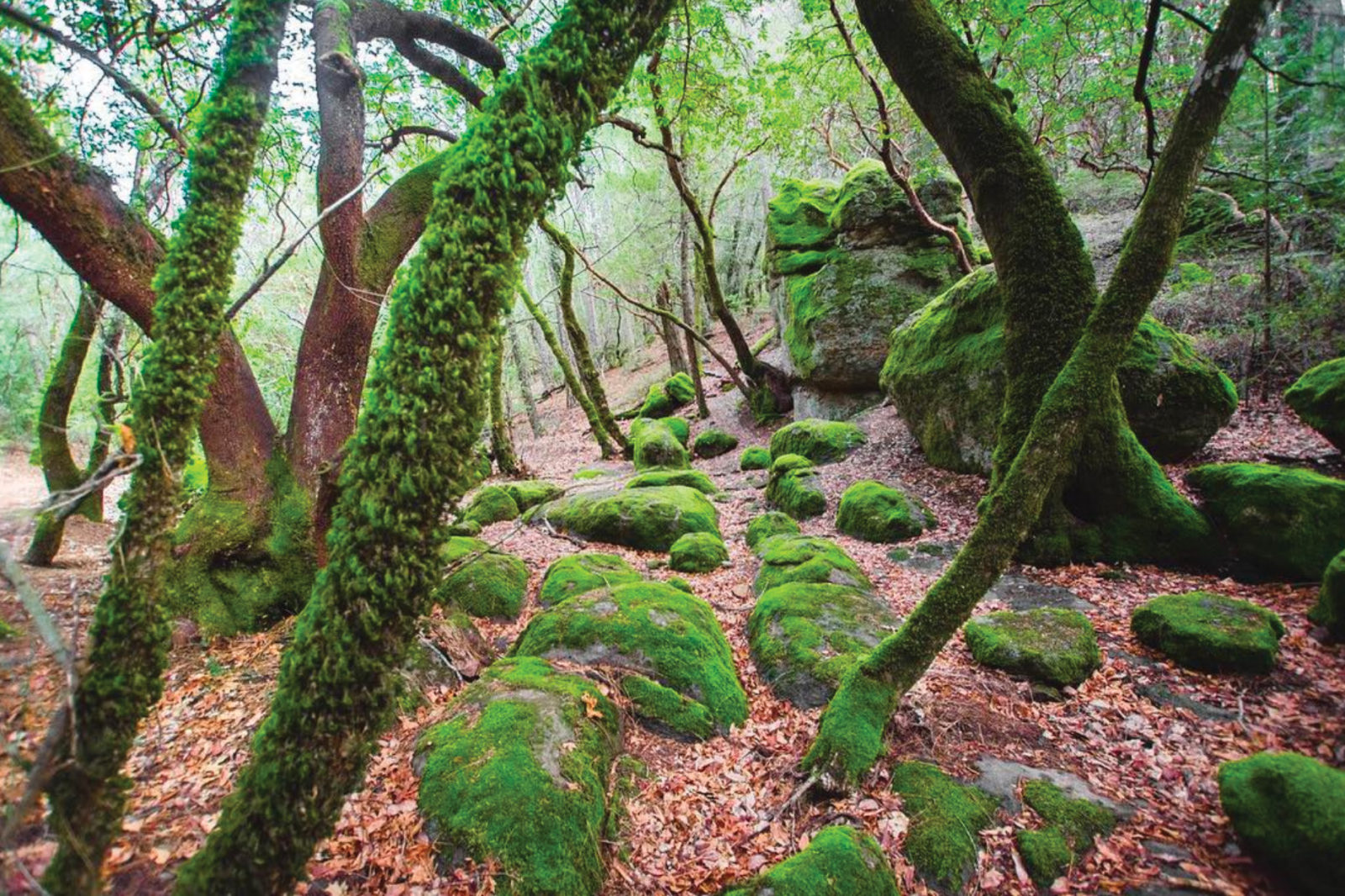

Underneath much of Napa and Sonoma counties lies the Sonoma Volcanics formation, and in the area around Angwin and northwest to Mount Saint Helena, a series of volcanic vents erupted tuff and andesite in fast-moving flows of debris some 3.2 to 2.8 million years ago. Boulders, often mossy green, are strewn around the forest like giant marbles. At one point during our walk, Lecourt picks up a glassy black arrowhead, saying, “You can find obsidian all over the forest here.”

The source was likely Glass Mountain, named for its outcroppings of volcanic glass, near St. Helena, and the Wappo probably crafted the arrowhead. The tribe lived throughout Napa Valley and beyond, gathering obsidian from the mountain to knap spearpoints and blades that were important in trade. Beginning in the 1700s, the succession of missionaries, Spanish colonists, and Americans in the area decimated the Wappo, whose last fluent speaker of their singular language passed away in 1990. The tribe continues to seek recognition of its tribal status by the federal government.

When you reach Redwood Flats, the first thing you’re bound to think is “nice place for a picnic!” Second-growth coast redwoods ring an open, level area where groups have often gathered. More golden leaves from black oaks cover the ground. There’s a spring tapped by a spigot. The water’s not treated but, it turns out, has everything to do with why these redwoods grow here, so far from the coast.

Humboldt State University forester Steve Sillett, who’s studying redwoods throughout their range, cored some nearby coast redwoods. These inland pockets interest Sillett because they survive in drier, hotter conditions. He says the trees often “are restricted to canyons and have their feet in water.” Where fog has a limited reach, mountain springs keep the trees hydrated. Studying these and other redwoods will offer more insight into how redwoods will endure the changes wrought by the climate crisis. “It’s a weird population,” Sillett says. “To see [redwoods] growing with chaparral and gray pine—you don’t expect to see that.”

Lecourt and I walk to the far side of Redwood Flats where a small amphitheater is carved out among the tanoak and Douglas fir. Rows of weathered, simple benches face a single old stump, a pulpit. On a summer day, it’s cool in the flats, Lecourt says, with the redwoods towering above, and the sun riding low. He called it “the beating heart of the PUC forest.”

Our walk back takes a turn up the steep “Anguish Hill,” so named by generations of students, as we head toward the ridge. We’re surrounded by the largest tanoaks I’ve ever seen. They’re easily 100 feet tall. There’s a soft thunk, thunk sound in the forest as the falling tanoak acorns hit the ground. Lecourt has plans for these tanoaks that are competing with the redwoods he’d rather see growing here. He may someday fell some of the oaks and experiment with replanting redwoods.

“So, I’m 34,” Lecourt says. “I hope to have this career for the next 30 to 35 years. I’m working on my vision for the forest, and we’ll see what I can get done.”