A siege of lightning strikes ignited 870 fires last August. Among the sites hit were six units of the East Bay Regional Park District. At first, the park district was on its own, scoping out the danger and using a park helicopter to scoop up water from reservoirs and ponds to protect people and property.

“Almost every hour you’d see smoke someplace where you didn’t expect it,” says Mike Mathiesen, the EBRPD assistant fire chief at the time. “It was kind of like playing whack-a-mole.”

Remember, they are an exotic species in the Western United States, and are rapidly increasing their geographic range and range of habitats. Are they outcompeting or excluding native species in the process? How would we know? We have done almost nothing to monitor changes in the assemblage of mushroom species in areas before and and after the incursion of death caps.

Further Reading

Pringle et al, “The ectomycorrhizal fungus Amanita phalloides was introduced and is expanding its range on the west coast of North America,” Molecular Biology 2009

Lockhart et al, “Simultaneous emergence of multidrug-resistant Candida auris on 3 continents confirmed by whole-genome sequencing and epidemiological analyses,” Clinical Infectious Diseases 2017

Battalani et al, “Aflatoxin B1 contamination in maize in Europe increases due to climate change,” Scientific Reports 2016

Explore: Oak Woodlands

» Visit the recovering landscape in Morgan Territory Regional Preserve on trails along its eastern border. From the staging area, choose a route to the Miwok, Manzanita, and Valley View trails, where you’ll walk through burned oak woodlands.

» The Morgan Territory Staging Area: Ample free parking, restrooms, water, picnic tables, and uneven cell phone reception.

» Dogs are allowed. Bikes and horses on designated trails. Some accessible trails.

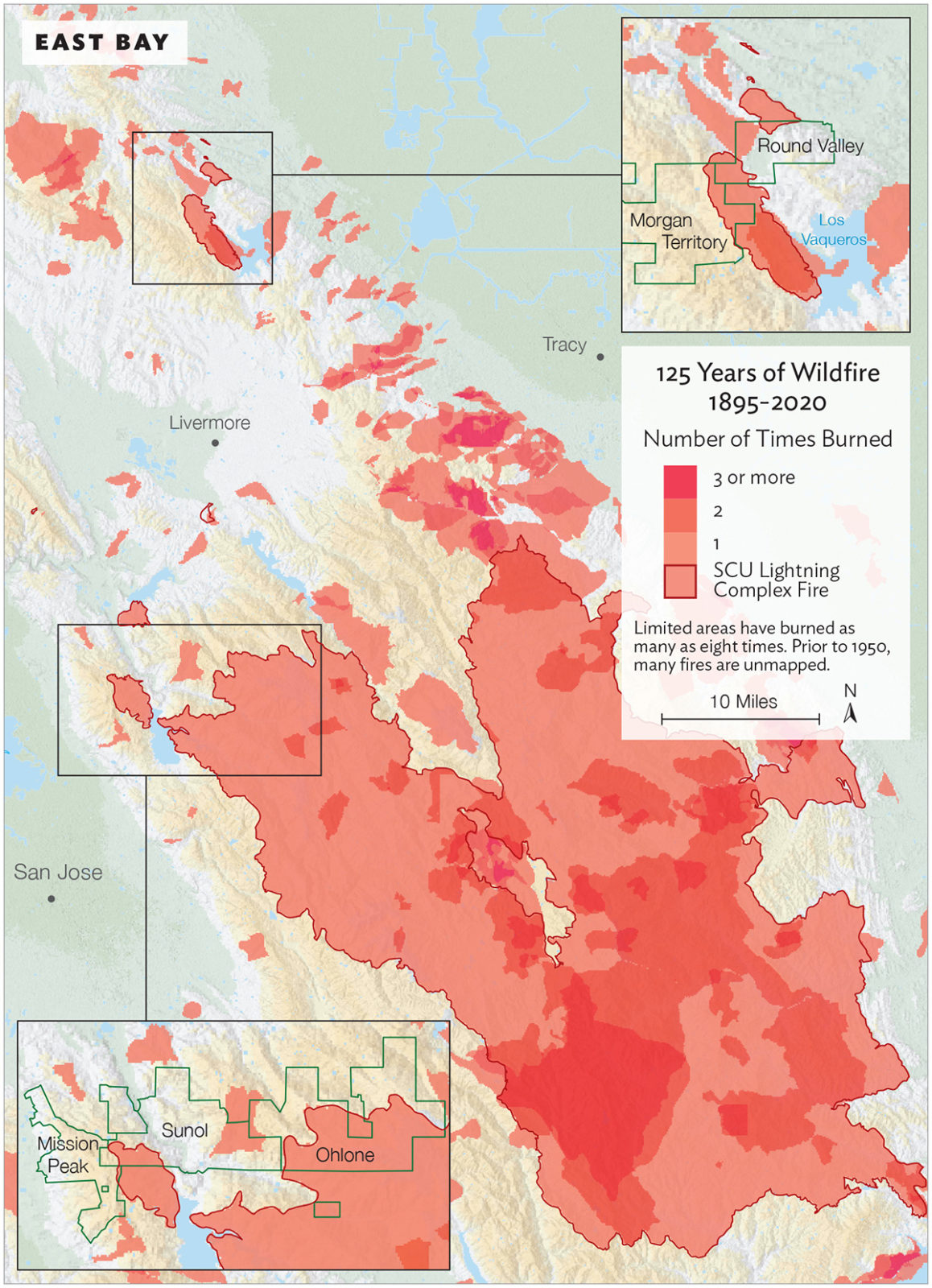

A few days later, the state’s firefighting agency, Cal Fire, joined the district to fight the rapidly merging Santa Clara Unit (SCU) Lightning Complex Fire, which by then extended from Morgan Territory and Round Valley regional preserves in the north to Henry Coe State Park in the south.

Mathiesen, a retired Cal Fire battalion chief, helped draw two “boxes,” or goals for containment. One was huge: 750,000 acres. Another, which kept the fire farther from population centers, was a little over half that size.

Ultimately firefighters succeeded in keeping the blaze within the smaller box. But it was still a big box. At nearly 400,000 acres, the SCU fire rose to third on the list of the largest fires ever in California. “It was pretty eye-opening to see the whole area that I have worked in for the last 26 years completely consumed,” Mathiesen says.

He also notes that much of the SCU fire was defined as “low intensity”—it cleared out understory vegetation that hadn’t burned in decades while leaving mature and healthy trees relatively untouched. “That’s going on statewide right now, where you have got so much fuel load in your watershed that something has to right itself, whether it’s through beetle kill or megafires.”

Down on the ground during the fires, EBRPD staff were working with Cal Fire to minimize the damage to park infrastructure and sensitive resources. Wildlife program manager Doug Bell served as the district’s liaison to the agency. Starting in the third week in August, he and other park staff fed Cal Fire information about where to go, places to protect, and problems to solve. It felt like being part of an army in wartime, Bell says, with firefighters and equipment operators dispatched every day to different crises around the SCU fire zone and beyond.

When the flames died down, park staff worked with Cal Fire on cleanup and repairs. A culvert under a park road had vaporized, making the road unsafe for vehicles. A bulldozer had torn through a rare serpentine grassland. Gates and fences were damaged. Park roads were rutted and dusty from weeks of heavy use. Downed trees and shrubs blocked roads. Heaps of vegetation were piled up along fuel breaks. With a team that included foresters, archaeologists, hydrologists, and soil scientists, Cal Fire’s repair process “was impressive and collaborative,” Bell says. “Their goal was to make us whole again.”

By the end of December, Cal Fire had done its best to clean up the damage its operations caused. But the chaos caused by the fire itself remained. About 6,000 acres in six parks had burned, including a few acres in Mission Peak and Pleasanton Ridge (four and 21 respectively) and larger areas at Morgan Territory (695), Round Valley (166), Sunol (498), and Ohlone (4,547).

“In some ways, we didn’t feel prepared,” says park district stewardship chief Matt Graul. Working with the district’s fire department, park officials had been trying to reduce fuels near cities by thinning eucalyptus and brush in the East Bay hills prior to the fires and had planned a prescribed burn at Point Pinole. But the district had never dealt with a fire this big.

In the aftermath, job number one was repairing fences and gates and roads, so cattle could graze and people could visit. But park officials wanted more than a safe reopening. They wanted to learn from the fires. They had hunches, but no hard data, about how East Bay plants and animals would now respond. They were determined to find out—and prepare for the inevitable fires of the future.

“I’m super curious to see how things are looking,” EBRPD vegetation program manager Dina Robertson says. “Someone told me they weren’t seeing a lot of regeneration.”

The eastern side of Morgan Territory Regional Preserve, a breezy outpost in the hills north of Livermore, was severely burned in places. Yet on a walk with Bay Nature in late February, Robertson points out stands of unscathed blue oaks surrounded by a cheery layer of green grass. “Some areas didn’t burn that hot,” she says. “Especially in our grasslands and oak woodlands.”

In fact, along sections of the Valley View and Manzanita trails where we walked, some grassy areas burned so lightly that even the cow pies are intact. Biologist Sue Townsend turns one over with a stick. The underside is damp and crawling with insects. “Refugia!” she declares.

Farther down the ridge, oak woodlands once underlain with shrubs reflect the first signs of an inferno. “The color of the soil tells you how hot it burned,” Robertson says, pointing to streaks of gray ash and red mineral soil where a shrub or fallen tree was completely incinerated. A small hole with ankle-high ash marks the former site of the plant’s roots. Around those ashy spots are broad areas of black soil. They look empty at first—but they are not.

Robertson points out the octopus arms of some emergent Indian (aka miner’s) lettuce. Then a lacy maidenhair fern. Then the lanky leaves of lilies and the round, pad-like leaves of shooting stars. The list of survivors lengthens as we walk: yarrow, geraniums, red maids, milkmaids. And finally, triumphantly: a fully grown warrior’s plume, with green leaves and blood-red bracts, coming up right when it usually does on this side of Mount Diablo.

Chaparral areas bore the brunt of the fire. But they’re coming back, too, with chamise, toyon, and elderberry sprouting from their own root crowns. In woodland areas, once lifeless-looking oaks and buckeyes are also reviving, with root sprouts and leaves coming directly out of trunks and large branches, a response to stress known as epicormic sprouting.

The jury is still out on the park’s manzanitas, known for their exceptional size and beauty. Outside the burn, these evergreen members of the Arctostaphylos genus have curvaceous limbs slathered with smooth red bark. Inside the burn, some manzanitas were skipped by the fire and still have green leaves. Others’ leaves are a burnt orange. Others, especially in severely burned chaparral areas, are little more than a stick in the ground.

Manzanitas have two post-fire strategies. Some species can sprout from a burl at their base, others only from seeds. Robertson doesn’t see sprouts of either kind on our February tour. But it’s too soon to draw conclusions.

This spring, Robertson and others will study the park’s vegetative comeback in four kinds of habitat: sagebrush scrub, chaparral, evergreen oaks, and deciduous oaks. She’s especially eager to find “fire followers,” species that only germinate in response to cues from fire, such as heat, smoke, or char.

As we head back to our cars, she’s feeling optimistic about the prospects. “I think it looks good,” she says. “We could see some cool fire followers in here soon.”

While helping with Cal Fire’s cleanup, Doug Bell scanned the landscape for wildlife. He trusted that many animals had scurried or flown to safety. “But some of those fires burned up a canyon in the middle of the night in an hour—incinerating everything,” he says. With pockets of fire so quirky and quick, he expects some animals got caught.

On one early reconnaissance, Bell noticed a rattlesnake rattle on the ground. “There was a hole next to it. So I probed and pulled out a three-foot snake that was very much cooked,” he says. “Obviously it was trying to get into the burrow and didn’t succeed.”

Some golden eagle nests were likely lost, too. “Eagles build these gigantic nests,” Bell says. “Several in the Sunol and Ohlone wildernesses are in gray pines, which tend to be Roman candles in fires.”

On the other hand, Bell (who leads the district’s long-term study of eagles around Altamont Pass) also knows of two eagles, outfitted with radio transmitters, that flew out of the burn when the fire started and returned within days. He was not surprised. “Eagles are scavengers,” he says. “So they’ll take advantage of a deer or even a cow that might have been killed by the fire. They also hunt in areas opened up by the fire, where prey are more vulnerable. You could call them fire followers, too.”

In a burned grassland, Bell was pleased to see chorus frogs and garter snakes swimming in a pond. “The pond itself looked untouched,” he says. At a similar site, he witnessed a scurry of ground squirrels. “You could see them kicking up dust and ash as they ran from burrow to burrow. It was kinda cute.”

At a bend in the road, Sue Townsend lopes up a steep hillside. Her previous work as wildlife ecologist has taken her from Antarctica to Mongolia, but her current focus is the Bay Area—especially filling in gaps of knowledge about common species such as bobcats and coyotes. “We know they’re there,” she says. “But we haven’t been systemically collecting data.”

Carrying a clipboard, hedge shears, binoculars, a pine stake, a GPS device, and a stuffed Star Wars creature (“Baby Yoda”), she’s obviously got more to do than gaze at the scenery. The park district hired her for her expertise in setting up motion-activated cameras.

Townsend makes a beeline to a camera on the hillside. Lashed to a pine stake, it’s taken 312 pictures in the past month, she says, including images of a coyote and a Steller’s jay. She quickly wipes off some dirt, swaps out the memory card, and checks the accuracy of the camera’s date and time. Then Baby Yoda (“a little smaller than a gray fox”) goes to work, posing on a log a few feet away to help Townsend adjust the camera settings. “Everything’s working,” she concludes. “It’s all good.”

Over the next three years, Townsend will repeat this process 12 times for each of 40 cameras a third of a mile apart, inside and outside the burn. New cloud-based software called Wildlife Insights will use artificial intelligence to help her sort through tens of thousands of images, identify animals, and make the data available not only to district decision-makers, but to a worldwide community of biologists.

“We used to put dead animals in museums that everybody could visit,” Townsend says. “Now we have a global network of camera-trapping projects. It’s a huge step forward.”

The park district is attaching sound-recording devices called AudioMoths to the cameras, as well as devices that record bats’ echolocation signals precisely enough to identify individual species. (These efforts will be supplemented by more traditional studies on threatened species such as Alameda whipsnakes, red-legged frogs, tiger salamanders, and western pond turtles.) The result will be a comprehensive picture of what creatures live here and how their populations respond to fire, seasons, and—if the studies can continue long enough—a changing climate.

“It’s impressive,” says Bell, who was trained at UC Berkeley in the more traditional data-collection methods pioneered by zoologist Joseph Grinnell. “This technology can capture information beyond our computational dreams.”

By mid-2021, it was clear that last year’s frightening inferno had tested and trained park district staff. They worked with firefighters and other landowners to save lives and property. They coordinated a complicated repair and cleanup effort. They reopened parks to the public and began detailed studies of what was lost, what’s left, and (in greater detail than ever before) how park ecosystems work.

There’s still much to be done. “We need to learn how Indigenous peoples managed the land with fire as an ally,” Bell says, and meanwhile also contend with afflictions such as drought, heat waves, plant and animal diseases, and, arching over it all, climate change. “We would like to see the persistence of landscapes and their flora and fauna, so that a hundred years from now people can still be enjoying them.” With that goal in mind, park defenders will face a host of new hurdles in the years ahead.

In the short term, though, park district staff are relieved about what happened last fall. “It wasn’t a perfect fire,” Bell says. “But, ecologically, it was probably a good fire.”