A radio version of this story was featured on KALW’s Crosscurrents program on June 24, 2021. Listen here!

Here are some scenes from the secret lives of animals Kendall Calhoun has seen on his study cameras: a wild pig walks the same route every two weeks; a fox has a squirrel in its mouth, then in the next shot the squirrel has escaped and the fox chases it; a bear takes a bath in an old water trough. With 36 motion-sensor cameras spread out over 5,000 acres of shrub, grass, and oak woodland at the UC Hopland Research and Extension Center in Mendocino County, Calhoun has captured a lot of candid animal moments. The cameras, triggered by movement and heat, take photos in rapid succession, so you end up with a kind of flipbook story. In the first shot of the bear, you see it approaching the trough. In the next shot, you see it climbing in. In the last shot, you see the bear sitting in the water, face forward, like a kid at bath time.

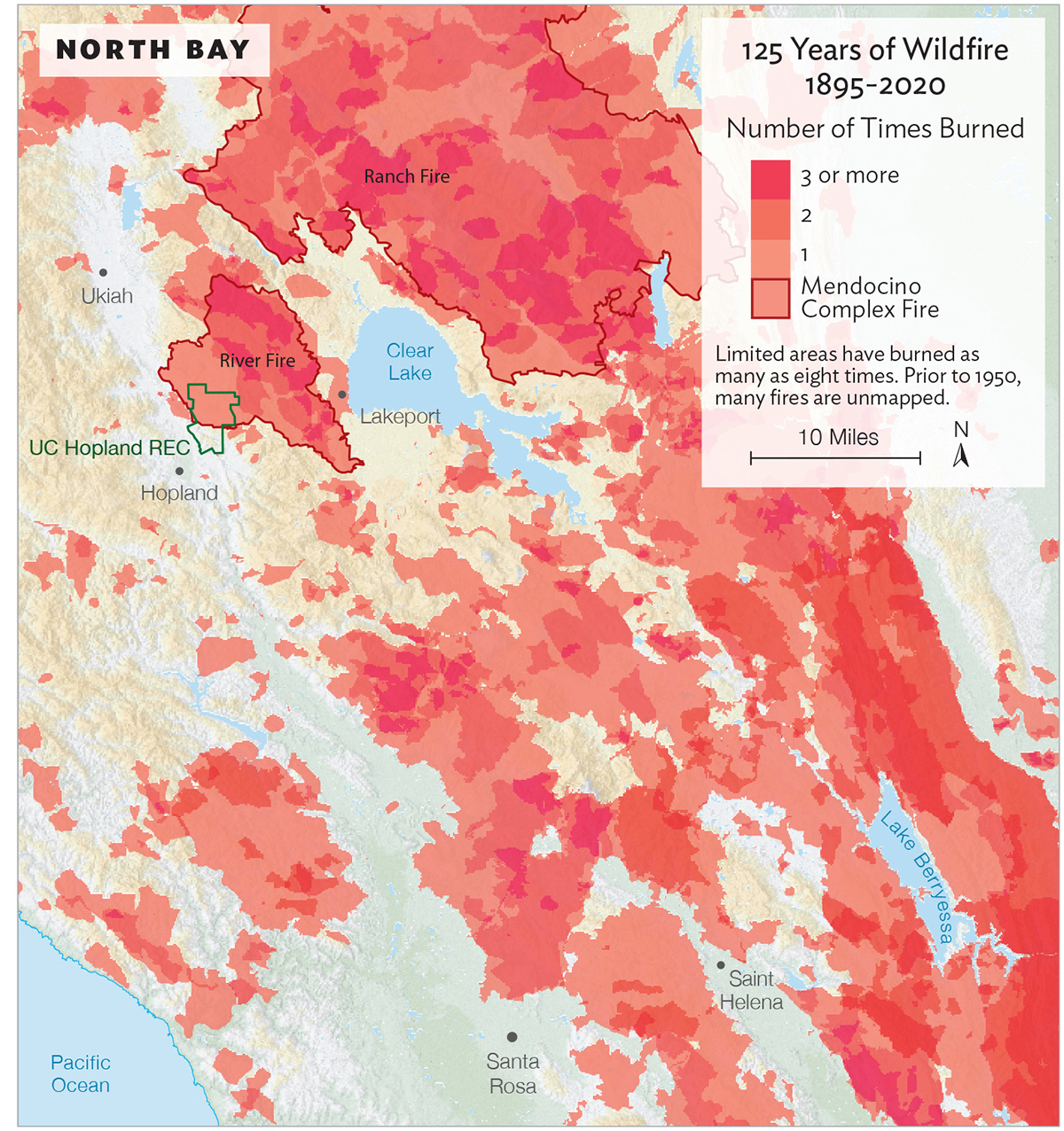

On July 27, 2018, the cameras captured a different flipbook story. At 5:50 p.m., a camera took a photo of the ridgeline in the distance, its edges being licked by flames. The Mendocino Complex Fire, California’s largest fire at the time, which started midday just north of Hopland, had reached the center’s property. The next photo, at 5:52, shows the grass in the mid-ground on fire, the ridgeline barely visible now because of smoke. At 5:53, the last image has becomea wall of flames, with more shooting out from the sides of the frame. The tree the camera was in caught on fire.

All but six of the cameras survived; the lost ones were replaced. Now Calhoun can use the footage from before and after the fire to study its long-term effects on wildlife. He is focusing on community ecology for his PhD at UC Berkeley—not just how a fire affects one species like deer or coyote, but how fire can start a domino effect influencing a whole chain of wildlife. He likes to think of community ecology as a movie with a huge ensemble cast. There’s the bear taking a bath, the pig with its regular walking routes—the individual characters “living their own interesting, individual lives.” But then the characters interact with each other as part of a larger drama. “That’s what makes it such a rich story,” he says, “learning about the roles of each of these characters” and what others they engage with, how, and when.

In the movie that Calhoun is studying, the overarching plot is fire. It seems like a question we should already know the answer to: what happens to animals after a fire? Not just during or in the days right after, but for the years following, as the vegetation slowly grows back? Ten years ago, scientists in California wouldn’t have really had an answer. Very recently, however, there was a study on birds and bats in the Sierra that showed fire changes the composition of species seen in an area; other studies have looked at the impact of the frequent grassland fires in the African savanna, which are somewhat comparable to California’s; and anecdotal observations suggest burned areas have attracted certain species and been avoided by others. But few studies examine how fire affects a whole community of animals in California. “To do the best kind of analysis, you need both pre- and post-fire data,” Calhoun says. “That’s really hard to get because how do you predict where the fires are going to happen?”

Calhoun takes me to one of the cameras in the burned area. It’s at the top of a mountain at the edge of the center’s land. This is where the fire moved in hot from the north and burned down into the valley below. At first glance, it doesn’t seem like the recent site of a “megafire.” There’s green grass growing underfoot. Oaks strike their usual poses. But the trees have no leaves and their burnt bark looks like cold charcoal briquettes. Fire is a natural part of the landscape here and can be beneficial to the ecosystem. But in patches like this one, where the flames burned hot, it killed off all the oaks.

Popping open the camouflaged metal box that’s tied around a tree trunk, Calhoun takes out the camera and SD memory card inside. Kneeling on the ground, he pulls his laptop out of his backpack and pops in the SD card to open the files. “Let’s see if we have anything interesting,” he says. The camera took 1,125 pictures over the last three months. He scrolls through the freeze-frames. “Oh, a bear! That’s cool.” The first year after the fire, Calhoun didn’t detect many large predators, but in the last year the cameras have captured photos of mountain lions and bears again. He keeps scrolling through images. “We have lots of deer, as you’d expect. Two bucks play-fighting or maybe they’re really fighting—I don’t know! Jackrabbits, more deer, and then us.” The camera took photos of our approach, a good sign that it’s working.

Calhoun visits each of the 36 cameras every three months to download the images. He’s also using recorders to collect bird songs at dawn and bat calls at night. He’ll use all this data to create models that show how animals on the property have been affected by the fire over time.

Calhoun’s starting hypothesis was that in the most severe, central parts of the burn, the overall wildlife community would be smaller—fewer species and fewer numbers detected. Mountain lions, which hide in shrubs to ambush their prey, would leave the area in search of places with more cover. Smaller predators, like coyotes and bobcats that normally cede turf to the lions, would increase.

He’s still analyzing the data, but so far Calhoun’s predictions have more or less played out. While bears and mountain lions temporarily disappeared, bobcats and skunks stayed and the activity of coyotes in the area has increased, likely because they’re generalists and will take advantage of any situation. There’s been a decline in squirrels, possibly because they weren’t fast enough to escape the flames or they’ve left in search of acorns. Jackrabbits, on the other hand, seem to have stuck around.

The deer have stuck around, too. In addition to the cameras, Calhoun utilizes data from GPS collars on 15 deer to reveal a remarkable story about what they did during the fire. Incredibly, they mostly stayed put, making “micro-movements” to avoid direct flames. Only one deer, known as “F-1” by its tag, hightailed it out of there, traveling a few kilometers to a neighboring ranch, but even that deer came back a few days later.

Even though all the monitored deer survived the fire itself, camera images show they lost weight. Calhoun says that’s not surprising, considering there was little food in the area for the first couple of months. That might have posed health risks, especially for does nursing fawns, for whom nutrition is critical. And while Calhoun isn’t studying the impact of smoke, research suggests it affects other mammals’ health just as it does ours. I think about how even we humans can’t measure a fire’s impacts by just the immediate lives or homes lost. We’re forever changed in similarly subtle ways: the post-traumatic stress some people develop surviving the ordeal; the residents who after losing their homes either move away or choose to rebuild and how that can change a community for years to come.

From where we’re standing at the top of the ridgeline, we can see down the valley and back up the hills to the other side of the Hopland land, where the fire didn’t make it. It doesn’t seem that far of a distance for a deer to walk. Why didn’t they just move over there? “I guess they’re weighing going into the unknown—where there could be predators—versus where they know and know how to be safe,” Calhoun says.

Calhoun has found that the deer at Hopland have doubled their home ranges, perhaps because they needed to go farther to find enough food. So, they can adapt, it’s just subtle. Is that enough to survive future fires? Calhoun says that’s the big question.

Calhoun’s research and use of camera traps to capture the larger picture about wildlife communities is part of a trend. Just outside Santa Rosa, Pepperwood Preserve installed a similar camera network across its 3,000 acres of chaparral, grass, and woodland habitat in 2012. Conservation science manager Tosha Comendant says it was the first rigorous study of its kind in North America. The goal was to gain a baseline understanding of the wildlife populations and how they’re affected by long-term forces like climate change. But in 2017, the Tubbs Fire burned 95 percent of the preserve. Then in 2019 the Kincade Fire burned half of the land again.

Comendant’s team is still analyzing the camera data, but even after that double whammy of wildfires, there are indications wildlife is recovering. Just months after the last fire, she says, bears and lions returned to the landscape. All the major animals normally found at the preserve have returned post-fire.

Pepperwood is also leading an effort to collect camera data from public lands across the Bay Area, aiming for an even bigger picture of wildlife in the region. During fires, do mammals move between different parcels of land? Do animals fare better if there is a cool stream nearby to provide refuge from the heat? What if the land is surrounded by homes—can animals escape? Comendant says a big takeaway is the importance of connected tracts of land that allow animals room to move. Humans need evacuation routes; so do other mammals, she points out. The fewer fences or other barriers there are, the faster animals can travel. After a fire, they need access to unburned areas to find food and shelter and reproduce.

Another important variable is burn severity. Comendant says the fires at the Pepperwood Preserve burned slowly and low across the ground, benefiting the ecosystem overall. But severe fires can burn such large areas that animals have few places to go and wait while the landscape recovers. Or a fire burns so hot that plants can’t rebound. Sometimes the oaks don’t come back, depending on the species, and the habitat becomes shrub or grassland, and the animal species that once lived there might not return.

At Hopland, in the worst areas of the burn, the dead oaks continue to fall. Calhoun wonders what the landscape will look like in the next few decades. How does this ensemble-cast movie end? For the animals, it’s going to come down to whether they can adjust to the progressively changing landscape. That might mean some groups slowly move to other parts of the land. It might mean new species move in as other habitats likely take over. And that might mean competition for the animals, a new actor in the story. “That’s why I like community ecology,” Calhoun says. “There’s all these characters playing into this big picture that we’re trying to make sure can continue to exist.”

Support for this article was provided by the March Conservation Fund.