The Russian River near Jenner–where the water runs wide and slow, and colorful sea kayaks dot the many miles of public access–is a well-known summer destination. But there’s another Russian River, a wooded green thread through the wine country where a river-level view gives a unique glimpse of wildlife and wildness persisting in an altered landscape. Here we can also see how decades-old contentions over water use and gravel mining have shaped the largest of our region’s coastal rivers.

To get a look at that other Russian River, I rented a kayak and put in near Asti, a small town 12 miles north of Healdsburg. It was early in the day; the conspicuous call of a belted kingfisher competed with the splash of my paddle. I looked up to see an improbably large chunk of dead wood lodged in a tree some 20 feet up, a high-water mark testament to the region’s short-lived but powerful rainy season. Flooding has long been a problem for homes built in the river’s extensive floodplain, and the watershed, including many tributaries, is punctuated by 62 dams, a flood-control measure that has wreaked havoc on fish populations. But long sections of the main stem flow unimpeded, including the 11-mile stretch I ran between Asti and Healdsburg.

- Much of the riverfront is in private hands, so paddling is the best way to explore the middle reach. At high water, this section also features stronger currents than the slack water nearer the mouth. Photo courtesy Russian Riverkeeper.

Of the Russian River’s 110-mile frontage, 95 percent is privately owned, so floating the river from one of the few put-in sites is the only way for most of us to experience this landscape. Once you’re on the water, the many vineyards that blanket the countryside are hidden behind a dense riparian woodland screen. Instead of traffic and tractors, you’re more likely to see an osprey feeding its nestling, or be startled by the prehistoric flap of a great blue heron rousted from feeding along the river’s edge.

But agriculture has a long history here. Ferdinand von Wrangel, who surveyed the river for the Russian American Company in 1833, made this assessment of the area: “[I]n the Slavyanka [the Russian name of the river] and other rivers flowing into it the Indians procure fish; superb groves of oak are inhabited by numerous wild goats [mule deer]; the grass is succulent; the land is excellent and capable of growing all kinds of grain, the vine, and the fruits of southern Europe.”

Today, the river continues to anchor this region, providing terroir famous the world over for “the vine,” as well as wildlife habitat and important natural resources. “When people think of the Sonoma County landscape–the vineyards, the redwood forests that border the watershed–it’s all tied to the Russian River. The river defines Sonoma County,” says Jake Mackenzie, Russian River Watershed Association chair.

- Thick riparian woodland along the Russian River near Healdsburg. The mature woodlands lining the river’s middle reach are important corridors for wildlife in this human-altered landscape. Photo by Frank S. Balthis.

- This mountain lion, caught by an automatic camera, was the only one documented by a study that found increased diversity of mammalian predators in sections of the river with wider riparian woodland strips. Photo by Jodi Hilty, Wildlife Conservation Society.

On the upper river, that may be as true for wildlife as it is for people. Because much of the county is a patchwork of often-fenced private homes and vineyards, predators such as coyote, bobcat, and mountain lion use streams as thoroughfares to move between remnant open space. Surveys done with remote-triggered cameras along the upper Russian and its tributaries show that the wider the riparian corridor, the greater the diversity of native mammalian predators. While the main stem’s setback requirement has been 200 feet for two decades, studies such as these made the case for a 2008 zoning change to require 50-foot setbacks along all the river’s year-round tributaries.

From Asti to Healdsburg, the flood-plain is relatively intact, extending several thousand feet on each side of the river. Karen Gaffney, a resource ecologist who lives along the river, describes the diversity of trees, the downed wood, and the layers of herbs and shrubs that help define a vibrant riparian corridor. “This is the sort of mix that makes for a mature riparian forest that supports the highest level of biodiversity. This stretch of the river has some room to spread out. And this section is better off than [downriver], where it’s more confined and the vegetation is less well developed.”

These riparian woodlands above Healdsburg are drier and hotter than the lower reaches. Even within the floodplain I see interior and coast live oak that don’t live along the lower river, and the redwoods that dominate the Russian’s lower reaches grow here only in smaller clusters along shady tributaries.

- The Russian River north of Healdsburg has warm riparian habitat that supports high densities of western pond turtles, such as those seen here sunning on a half-submerged tree. Photo courtesy Russian Riverkeeper.

That warm riparian climate provides the perfect habitat for western pond turtles. They live in the highest densities north of Healdsburg, and it’s common to encounter a klatch sunning on a log. “Our population is strong,” says Dave Cook of the Sonoma County Water Agency. “Pond turtles have two things going for them: They are durable, with that hard shell. And they are long-lived, so you can have a decade of poor conditions and they can still come back.”

Also, keep an eye out for river otters–the Russian has a healthy population. If the otter itself eludes you, look for its prints (pointed toes and webbed feet) along the muddy frontage, or its den (called a “holt”) burrowed along the bank.

Things are not going quite so well for the river’s three species of salmonids: coho and chinook salmon and steelhead trout. These fish once thrived in the river’s many side tributaries and wide floodplain. Although historically sections of the river dried up during the summer, deep pools connected by underground flow offered good fish habitat. Today, all three fish are listed as threatened or endangered under the federal Endangered Species Act.

But the situation is better here than in many other watersheds. While steelhead and salmon numbers have declined dramatically along the river–affected by years of overfishing, gravel mining, and increased sedimentation from logging and agricultural practices–the Russian currently supports a relatively stable population of chinook; surveyors from the Sonoma County Water Agency regularly document 25- to 30-pound chinook coming upriver.

- A steelhead trout rests in a pool. Steelhead and salmon once thrived in the watershed, but populations have fallen drastically. Steelhead remain the most numerous salmonids in the river, though chinook salmon are doing better here than on many other California rivers. Photo by Justin Smith, UC Division of Agriculture & Natural Resources Cooperative Extension.

And with the fish come bald eagles. Once near extinction locally, bald eagles have returned to the river and can be found nesting at both Lake Sonoma (on tributary Dry Creek) and along the upper Russian River. Bald eagles create the largest nests of any North American bird–these can be a dozen feet deep and eight feet across–which makes them easy to spot from the water.

Though the river remains critical wildlife habitat, the entire course of the Russian has been highly altered over the last century. The river springs from Mendocino County’s Laughlin Range, just north of Ukiah. Historically its flow varied with the seasons, with some sections slowing to a trickle in summer. But all that changed in the early 1900s, when engineers harnessed the difference in topography between neighboring rivers: The headwaters of the Eel River flow only a few miles north but several hundred feet higher than the Russian’s headwaters. A utility company diverted a significant portion of the Eel’s flow through a tunnel to drop into the Russian River drainage in Potter Valley, harnessing the energy of the water’s 300-foot fall via a hydroelectric power plant. That diversion has provoked a dispute between Mendocino and Sonoma counties that is being debated in court to this day. Water from the northwest-flowing Eel provides the east fork and the main stem of the upper Russian a respectable year-round flow, fueling Sonoma County tourism and agriculture.

But Sonoma’s boom has happened at the expense of the Eel’s fish population, and federal regulations recently have required that the Russian take 30 percent less Eel water. Even with that reduction, the Russian River still relies heavily on the Eel.

The Russian’s flow still varies dramatically depending on three variables: rainfall, water from the Eel, and water released by the dams at Lakes Mendocino and Sonoma. In late winter the upper reaches can run fast–I completed the 11-mile journey from Asti to Healdsburg with Class 1+ rapids (a step above flat water) in just a few hours. The water slows down in summer and early fall as rainfall abates, a better choice if you’re looking for a more leisurely slack-water ride, assuming there’s enough water in the river to keep your kayak from scraping the river bottom.

- Gravel mining along the river has damaged habitat and increased water temperatures, both of which make life harder for salmon and steelhead. Photo (c) Barrie Rokeach 2009.

Flows this summer may drop to that low level, given that the Sonoma County Water Agency has received permission from the California State Water Resources Control Board to make 2009 a “dry” year flow along the Russian. The water agency wants to hold water back from Lake Mendocino during the summer months to ensure the reservoir has reserves to release in the fall for returning salmon and steelhead. Fall is the time to witness the chinook salmon coming upriver to spawn, and this year’s low flow should make spotting them even easier.

Five miles into my journey, I beached for lunch along a wide wash of rounded river rocks. While a comfortable spot for a break, this too is altered landscape, caused by mining for aggregate, the loose rock used to make concrete. Rock is no longer mined from the river bed itself, but it’s still “skimmed” off the river’s edge in the middle and upper reaches.

Both types of mining damage riparian habitat, cause erosion along the banks, and, says Joe Dillon, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s water quality coordinator, ultimately increase water temperature, all bad news for fish: “We don’t have extensive layers of trees along the length of the river to shade the water, and that makes water temperature go up. The mining also increases sedimentation, so we’ve lost many of the cold, deep pools needed by salmonids.” According to the Trust for Public Land, the main stem of the upper Russian lost 30 percent of its riparian vegetation between 1940 and 1990. It’s estimated that the anadromous fish population in the watershed has declined by 90 percent since 1940.

Given that situation, restoration work on the river focuses on the fish. One seemingly counterintuitive recommendation for fish habitat restoration is to reduce summertime flows. Most of us imagine that for a fish, more water is always better, but not so here. Most of the watershed is drastically hemmed in, causing water to move within its constrained course too quickly. “We have confined it to such a small area,” says Dillon, “so the river has too much force–it erodes the stream and puts sediment on the banks.” All of which damages spawning grounds. Less water will mean slower flows, and that will improve the fish’s prospects.

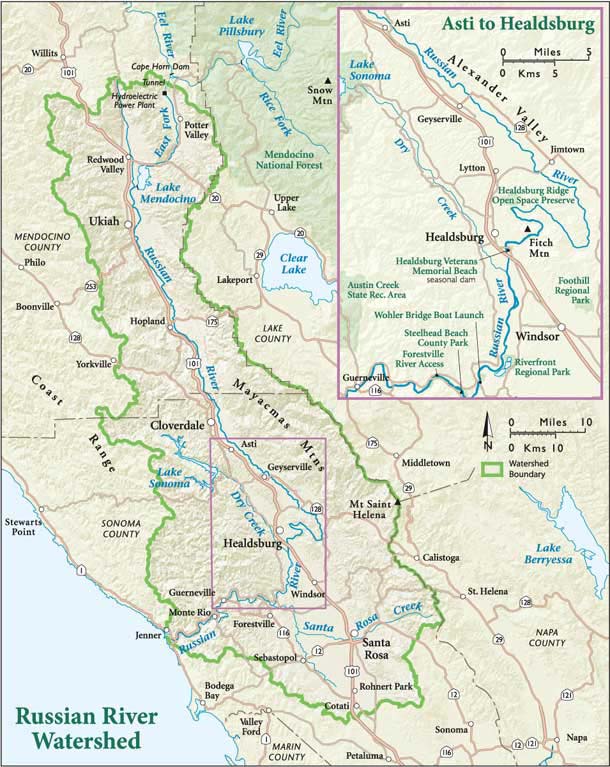

- Click on image to see larger version. Map by Ben Pease, www.peasepress.com.

The Russian is a complex watershed, with hundreds of tributaries feeding the main stem. Biologists believe these tributaries once provided extensive spawning habitat, and efforts to improve the many side channels are also under way. Dry Creek, one of the river’s main tributaries, enters the Russian just below Healdsburg. The lower 14-mile section of Dry Creek carries water from Lake Sonoma into the Russian River. This fast-moving water makes it difficult for young fish to thrive, so Dry Creek is undergoing significant habitat restoration intended to create pools during summer and provide areas where fish can escape high winter flows. Landowners along Dry Creek are removing invasive plants, controlling erosion, and removing culverts that block fish passage. Organizations such as the Russian River Watershed Council are educating the local public to ensure water quality and the biological health of the watershed, all to support the salmon.

The river changes both temperament and direction below Healdsburg, where it takes an uncharacteristic turn due west and the flow slackens. This is where the Sonoma County Water Agency snags water for its municipalities. Most Sonoma County cities and towns receive their drinking water from the Russian River, and Marin County gets 20 percent of its drinking water from the Russian as well. That’s not counting the hundreds of agricultural and residential wells along the river.

I take out on a grassy river terrace before the river’s westward bend at Fitch Mountain. Through the trees I can see fields of vines and several houses hidden behind a row of redwoods. Though civilization was always lurking beyond the treetops, time on the water managed to narrow my field of vision to that green thread of wildness that still snakes through this altered landscape.

Getting there

River’s Edge Kayak and Canoe leads trips on this section of the river and will provide shuttle service if you own a kayak [(707)433-7247]. Or go on your own and put in at Alexander Valley Campground [2411 Alexander Valley Road; check in with the campground host, (707)431-1453]. Take out at Healdsburg’s Memorial Beach.

.jpg)