What are some of the first things I should look for when tracking animals? —Nick in Fremont

I used to think I was a good tracker. I even taught classes, but the more I learned about tracking, the more I came to realize I didn’t know scat. However, Nick, one of my first tracking lessons was actually from those classic children’s books: “STOP, LOOK, AND LISTEN!” And, I’ll include, SMELL.

In this frenetic world of ours, tracking—observing the signs left by animals so as to know who’s been there, or to follow them—forces me to slow wayyyyyyy down. I use a Zen technique called beginner’s mind, which is all about removing preconceived notions. You should open not only ears, eyes, and nose but also your heart to what’s going on around you. And while it’s critical to have basic tracking knowledge, also be open to all possibilities.

To start out in tracking, there are many great reference books. Get one that is, at least broadly, specific to your geographic area. (I like the Field Guide to Mammal Tracking in North America, by James Halfpenny, or the UC Press Field Guide to Animal Tracks and Scat of California, by Lawrence Mark Elbroch.) Before you start tracking animals outdoors, it’s worth reading the entire book, or better yet books, while sitting quietly in the comfort of your living room.

Start LOOKING with animals’ prints, where you can observe the three major ways mammals walk. Cats, birds, and dogs walk on their toes and sometimes press down with the ball of their foot: digitigrade. Raccoons, possums, bears, lizards, and humans walk with their entire foot: plantigrade. Horses, deer, and sheep walk on their hooves: unguligrade.

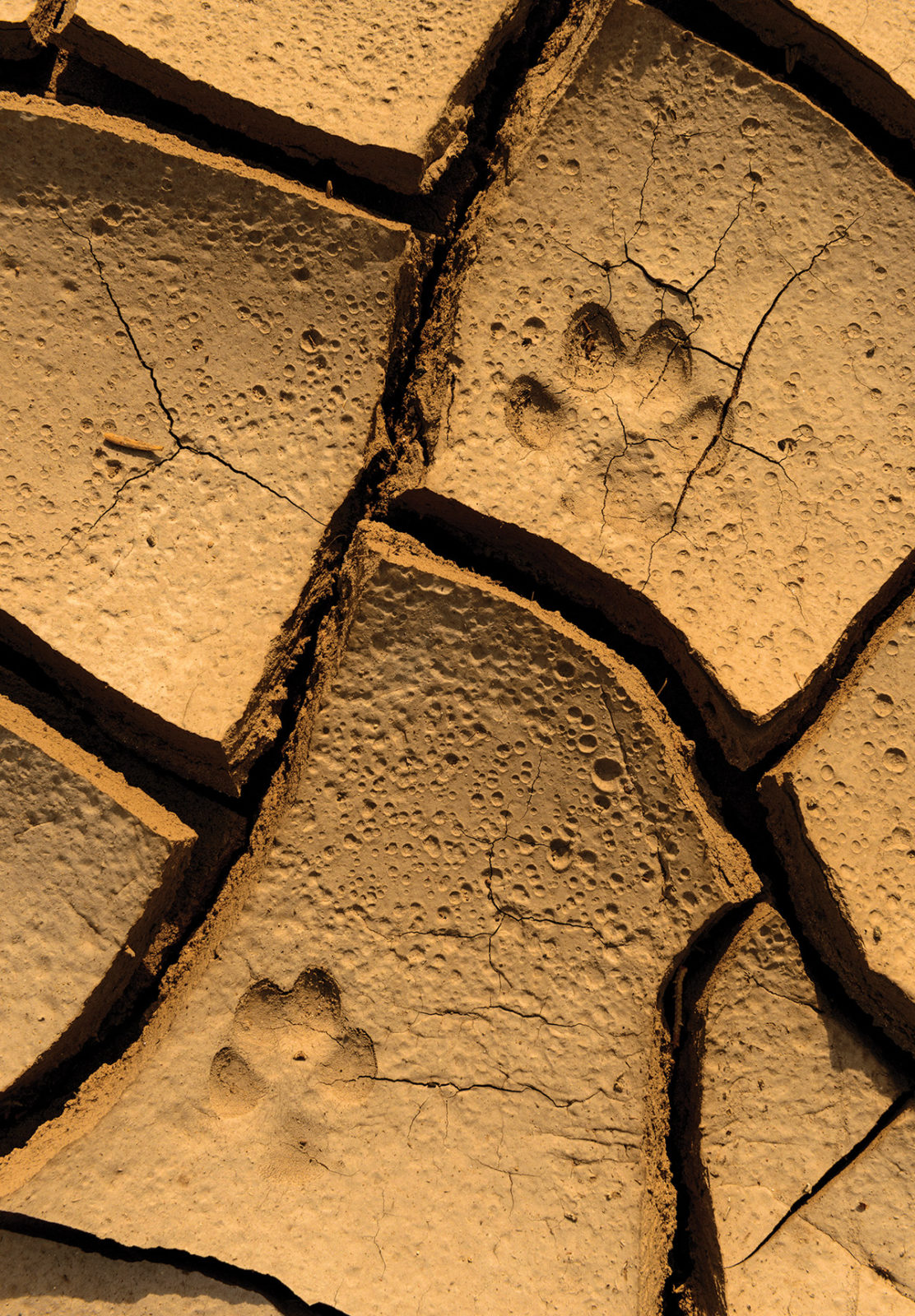

Nail or claw marks may appear in some tracks (canines, raccoons, bears) and be absent in others (cats). Of course, the substrate is uber-valuable in identifying tracks. A fresh rain that leaves the soil or sand damp and the edge of a mud puddle can perfectly capture a print, but dusty fire roads also work well. On camping trips or on safaris, I often gently sweep an area clear of tracks in the evening so I can decipher the nocturnal activity the following day.

From prints you can deduce gait, the overall movement. Measure the distances between prints, and take photos using a ruler for scale. Later, back home with the field guides, you can reevaluate the tracks.

Different teeth and feeding techniques also leave characteristic signs in munched vegetation and in undigested food and metabolic wastes (aka poop), which are essential for determining whether an animal is a carnivore, herbivore, omnivore, grazer, or insectivore. In some droppings there are two components: dry, white uric acid crystals and undigested food. This is bird or reptile waste. Mammals process metabolic wastes differently and excrete by-products and chemical messages in liquid urine. One more or less uniform poop mass is most likely from a mammal. Piles of scat often mark both trails and territory edges. Huge latrines full of “broken cords” are from raccoons.

Watching and LISTENING to birds and chattering rodents is also a form of tracking. Many mammals and birds use different vocalizations depending on the situation. Quail have a certain “pit-pit” call alerting large coveys to possible danger. Wild turkey calls might distinguish between a harmless snake and a rattlesnake. No doubt you’ve heard alarm calls from Steller’s jays broadcasting “naked clumsy ape in the forest.” Gray squirrels have different alarm signals. One vocalization is for avian predators and a tail flicking warns of a feline predator.

We humans with our inferior noses mostly miss the information swirling around on the trail, but it’s still worth stopping to SMELL. Most mammals are nocturnal and communicate primarily with scent. Skunks, members of the weasel family, muskrats, deer, and elk all emit strong olfactory signals at times. Male deer and elk emit some potent-smelling urine during rut. Otter and mink scat, sometimes found midstream on rocks, is really stinky.

So, Nick, there is something very Zen about being out on a trail and slowing down enough to notice all the things around you. And not just the signs that animals leave behind, but the dripping fog off the leaves, the curve of the tree letting you know which way the dominant wind blows from, the flow of the water in this particular watershed, the echoes of other humans who walked this land long ago, and the awareness of those who will be here long after you are gone.

STOP, LOOK, LISTEN, SMELL!