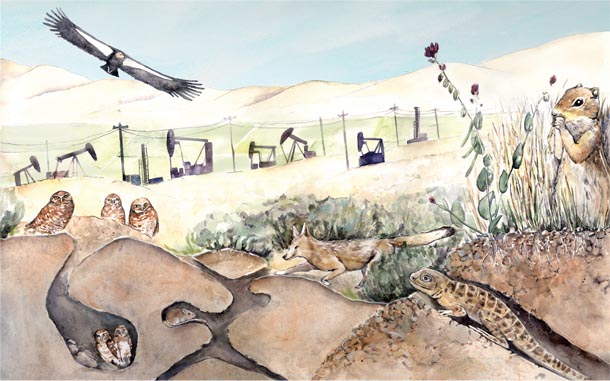

The condor launches from a rocky outcropping in the Santa Lucia Mountains near Big Sur in Monterey County. To the west lies the Pacific Ocean, a rich source of food for the bird when a dead seal or whale washes ashore. To the east lies the Salinas Valley, an area where ranching and farming operations can provide the scavenging condor with the occasional dead lamb or steer. The condor keeps gliding, her ten-foot wingspan casting fringed shadows over wide-open country that’s home to endangered San Joaquin kit foxes and giant kangaroo rats that hide by day in dens and burrows and blunt-nosed leopard lizards that bask in the sun. The condor is headed for Pinnacles National Park, or perhaps the Joaquin Rocks, two favorite roosts that involve a 100-mile journey, an easy stretch over the course of a few hours for this massive bird.

Near Highway 101, about 20 miles north of Paso Robles, the condor crosses the San Ardo oil fields, where flares illuminate the sky at night. These oil fields have been in operation for more than 60 years, but more recently-developed methods such as fracking (short for “hydraulic fracturing”) and horizontal and directional drilling are promising to create a new boom due to the prodigious quantities of oil trapped in the shale layers of a widespread geological structure known as the Monterey Formation.

Outcroppings of this 1,750-square-mile formation are visible as far north as Grizzly Peak in the Berkeley Hills and Kehoe Beach at Point Reyes. But the drilling action will be concentrated to the south, from Monterey and San Benito counties south to Kern and Ventura counties, in areas that mirror the condor’s historic range and represent some of the last fragments of undeveloped habitat for condors, kit foxes, kangaroo rats, and leopard lizards.

Geologists estimate that this region contains as much as 15.4 billion barrels of oil, which would make it the nation’s largest domestic source of recoverable oil. Oil industry proponents claim that increased fracking to recover this oil would bring thousands of jobs and billions in tax revenues to the state. Moreover, they claim, fracking has already been used safely in California for decades. Environmentalists express a different view, pointing to potential threats to groundwater, sensitive species, and the integrity of the ground itself. However, efforts to pass a moratorium on fracking — or even a hiatus while the process is studied further — have so far been stalled in the state legislature.

Officials with the federal Bureau of Land Management (BLM), which oversees a vast amount of publicly owned land in California, don’t foresee an oil development explosion on previously untapped lands anytime soon. But the pressure to exploit these resources isn’t going away anytime soon either, nor is the debate over the wisdom of doing so. As we weigh the pros and cons, a missing piece of the conversation is the land itself: What is the Monterey Formation? What is it made of and how did it get here? And what kind of habitats, plants, and animals live atop it?

Monterey Shale in Berkeley?

Geologist Mel Erskine parks his car on Grizzly Peak Boulevard in the Berkeley Hills and grabs a small metal pick from his trunk. The road offers dramatic views of San Francisco Bay, but Erskine turns his back on the vista to focus on a lowly rock outcropping on the opposite side of the road.“This is the Monterey shale,” Erskine says, pointing at a yellowish-orange outcropping that is marked by rows of vertical fractures.

The shale, which is the oil-bearing component of the Monterey Formation, is very brittle, which is one of the reasons it can be fracked, Erskine explains, breaking off a small chunk with his pick. A thin dark seam of oil glistens, then fades, like jelly in a peanut-butter-and-jelly sandwich. “This is what we are trying to get to through hydraulic fracturing,” says Erskine, indicating the thin dark seam, which is where high pressure and temperature have converted microscopic marine organisms into oil over millions of years.

Could this ridge in Berkeley get fracked one day, when oil gets scarce enough? Erskine shakes his head and looks from the outcropping to the cliff edge, the steep drop, and the breathtaking views of the Bay. The search, he says, is for areas where the Monterey shale is nearly horizontal and less structurally deformed. “Fracking can handle some dips,” Erskine says. “But basically they’re going horizontally because they want to inject uniform pressure over a large area. In a steep dip like this there is no way to control the fractures.”

Erskine rolls out a geologic map of California that depicts the Monterey Formation extending beneath central and coastal California and out into the Santa Barbara Channel. “It’s a formation that accumulated in deep structural basins during the Miocene period,” he explains. “It’s very young.” The fine-grained sediments that eroded off the land into the ocean to form the shale were deposited in several offshore marine basins over several million years, between 13 and 6 million years ago.

Over that same period, dead microscopic marine plankton, both plants (diatoms) and animals (especially radiolaria), rained down onto the seafloor, then got covered and buried by younger sediments and were very gradually altered into hydrocarbons embedded in the shale matrix.

Compared to North Dakota’s Bakken Formation or the Northeast’s Marcellus, the Monterey Formation is younger, with more internal folding, and it’s in earthquake country. “All those black lines on the map are fault zones, so it’s very complex,” Erskine says.

You might think, with all that natural fracturing, fracking might not even be necessary. Not so. Erskine explains that the Monterey shale is like a continually flowing subterranean creature, active and dynamic, so new fractures heal quickly as tectonic forces push and pull the rock. Fracking injects large volumes of water and a mix of sand and chemicals into the fractures in order to keep them open. After the water-chemical mixture is pumped out, the oil liberated from the fractured rock flows into the well.

Who Lives Here?

Of course, the impacts of fracking don’t just occur underground. The surface above the Monterey Formation is home to an array of wildlife and plants that may or may not take well to the scattering of wells, roads, wastewater trucks, and other equipment that accompany an oil boom.

The blunt-nosed leopard lizard, the San Joaquin kit fox, the giant kangaroo rat, the California condor, and San Joaquin woolly threads are among the rare, threatened, and endangered species that the BLM listed in the environmental assessments it prepared for the leases auctioned for oil exploration in 2012.

It isn’t easy to find a blunt-nosed leopard lizard, unless you visit senior researcher Theodore Papenfuss at UC Berkeley’s Museum of Vertebrate Zoology. For the past 15 years, Papenfuss has studied the lizards in Kern County, near Taft and Maricopa, the site of oil well development since the late 1800s.

As Papenfuss leads me by a stuffed condor and the shell of a giant tortoise, he explains that even if leopard lizards are on a piece of land, you might be near them but never see them, since they hide out in burrows during the heat of the day. “They have a very definite territory, so they can’t just scamper somewhere else,” he says. “And there’s a balance with kangaroo rats, too, since blunt-nosed leopard lizards live in their abandoned burrows.”

He leads me into a vault that contains thousands of jars full of preserved lizards. “The blunt-nosed leopard lizard is not only federally endangered but also fully protected [by California],” says Papenfuss, retrieving a jar of the lizards, which are sandy in color and spotted. It was the fast pace of development and consequent loss of habitat following the construction of Interstate 5 that led to their endangered status. “When I-5 opened, you could drive long distances and see semi-arid shrubland,” Papenfuss says. “Now it’s almost all disappeared.”

Due to the lizard’s protected status, developers are required to do careful surveys before they can even propose a project on potential lizard habitat. Seismic testing, well construction, and vegetation removal to prevent brush fires can all be detrimental to lizards and other ground dwellers. “The well itself may only be three feet in diameter,” Papenfuss says, “but it has a huge area around it, including the infrastructure, such as pipes, trucks and storage tanks.”

Despite these challenges, David Germano, a biology professor at Cal State University Bakersfield, says blunt-nosed leopard lizards still occur in areas with low-to-moderate oil development. “They can occur near oil pumps,” Germano wrote in a recent email. “Although any loss of habitat is incrementally harmful to this species, the actual operations of another method of oil/gas extraction isn’t likely to be a major concern.”

On the Ground in the Frack Zone

It’s midnight as BLM biologist Mike Westphal drives past a windswept plateau west of Interstate 5, deep in the Panoche Hills, a rugged badlands punctuated by saltbush, grasses, and discarded beer bottles. “Where it’s flat, that’s where they live,” says Westphal, who is using a handheld spotlight to illuminate the eyes of kit foxes in the maze of razor-backed ridges, steep canyons, and occasional valleys. “There it is!” he shouts, as the light picks out two emerald spots, a couple hundred yards away. “There’s two of them,” he adds, as another pair of eyes blinks. “And they’re too low to the ground to be coyotes.”

Westphal performs night surveys of endangered species, including San Joaquin kit foxes, a couple of times a year. The rest of the time, he relies on dogs that go out in the morning, when kit foxes are asleep, to locate the animals’ scat. This approach has allowed him to identify 100 kit fox individuals in this area over the last four years. “The biggest threat is development,” he says, referring to the irrigated ranks of almond trees and grapes that now flank I-5, displacing the arid, sandy conditions in which kit foxes, kangaroo rats, leopard lizards, and other desert species flourish.

Luckily, grazing is a more harmonious match, Westphal observes. “Where nonnative grasses are thick, endangered species vanish, so if we can keep the ranches, both endangered species and ranches win,” he says. So far, fracking is only marginally on Westphal’s radar. He’s more concerned about plans for a large solar plant in the Panoche Valley than oil development on BLM land. “We’ve seen zero wells go in over the past 20 years, even with the lease sales,” he says.

But not everyone is so sanguine about the future. The Salinas Valley is part of a kit fox satellite recovery area. Paula Getzelman, a vineyard operator in Lockwood, has seen foxes, badgers, elk, coyote, and deer on her land near Lake San Antonio. “You can see their trails down to the lake,” says Getzelman, who started educating herself about fracking two years ago, when an exploratory well was drilled ten miles from her place.

She worries about what fracking could do to the water supply in an already water-hungry state. “Oil is important, energy is important, but once you’ve ruined the environment you’re done,” Getzelman says. “In an area where agriculture drives the economy, that’s a harsh reality.”

Michael Kiparsky coauthored an April 2013 report for UC Berkeley’s Center for Law, Energy & the Environment that focuses on the risks that fracking could pose for water supply and quality. He warns that contamination of underground sources of drinking water is possible when developers drill through aquifers en route to oil reserves in the shale.

“When a hole is drilled, it creates a conduit through which oil, gas, and fracking fluids could move upwards,” Kiparsky says. “If there was a casing failure, that movement into the bottom of the aquifer could happen within hours or days, but wouldn’t necessarily be visible at the surface for decades or centuries.”

Kiparsky says that in 2011, the average fracking operation in California used 150,000 gallons of water per well, according to figures from the California Independent Petroleum Association.

“To put it in context, fracking operations used a reported 202 acre-feet of water in 2011 for the entire state of California, compared to the million acre-feet the State Water Project uses every year,” Kiparsky says, referring to diversions from the Sacramento–San Joaquin Delta that support agriculture in the San Joaquin Valley. “That’s not to say that fracking doesn’t impact the local water supply, but [the overall impact] will depend on the quality of the water and how much fracking operations take away from other uses.” Kiparsky recommends a baseline of water quality monitoring along with public disclosure of the location and contents of fracking fluids and injection well sites.

Fracking in a Fault Zone

It’s those injection wells that also worry Peggy Hellweg of the Berkeley Seismological Laboratory at UC Berkeley, much more than the actual fracking.

Fracking leaves behind contaminated “produced water” full of residues that “you have to handle as a hazardous waste, and rather than cleaning it up, it’s easier to pump it down some hole you don’t need anymore,” Hellweg explains. Those “holes”— or injection wells — are often old oil wells that are no longer producing. The residues in the water aren’t the only problem: It is these types of wells that have been associated with earthquakes in other parts of the country and are therefore a source of alarm in quake-prone California, which contains about 30,000 injection wells.

Hellweg notes that of the tens of thousands of injection wells in the U.S., very few are associated with larger earthquakes. A 5.6-magnitude quake in Oklahoma in November 2011 is the biggest potential suspect to date, pending further review by geologists. “But there are studies that show that in a given tectonic setting, the more strongly you inject, the more likely there are to be earthquakes,” she says.

While scientists don’t completely understand the process, Hellweg explains that as the “produced water” is injected for disposal, it infiltrates pores in the rock, raising the pressure locally and counteracting the tectonic pressures that keep the opposing sides of a preexisting fault pressed together. “In a few cases the raised pressure from the injection could overcome the local stress regime, allowing any shear forces to rupture the fault, resulting in an earthquake,” Hellweg says.

Bill Ellsworth of the U.S. Geological Survey’s Earthquake Science Center in Menlo Park concurs and advocates better reporting about disposal operations at injection wells to go along with the already-robust seismic monitoring systems throughout much of the area proposed for fracking. “It would improve our understanding of why only a few injection wells are seismic problem-children,” he says.

Weighing the Costs

Over the past year, there was a flurry of proposed legislation to tighten the regulatory leash on fracking. California State Senator Bill Monning, whose district covers much of the Central Coast, is a cosponsor of Senator Fran Pavley’s (Southern California) SB 4, which seeks greater regulation for all “enhanced recovery methods” in the state. He has heard the argument that it’s essential to explore and exploit the oil in the Monterey Formation to reduce dependency on foreign sources. “The real cause for concern is the advent of a potential expansion,” Monning says. “When I look at the cost of technology and the environmental impact of extraction, we should put that on the balance sheet.”

The condor circles back toward her nest among the rock spires of the Pinnacles, flying high over a dramatic California landscape of rugged hills and open valleys shaped over eons by the encounter of two of the earth’s great crustal plates. It is perhaps ironic that the same dynamic geology that produced some of the greatest biodiversity on the planet — a biodiversity that has nurtured the condor and the kit fox and the leopard lizard over millennia — has also produced a substance that drives our economy and whose extraction may soon pose a threat to that same biodiversity, not to mention our groundwater, agriculture, and air quality. Before we attempt to squeeze the last drops of oil from the ground, like blood from a stone, we might want to take that condor’s-eye view of California’s manifold riches and consider leaving “well” enough alone.