How often have you encountered a trail, campsite—or even an entire park—with an odd or mysterious name?

Eighty-five years ago, visionary academics, public officials, and hikers, living mostly in Oakland and Berkeley, convinced public agencies to convert hilltop watershed lands to public parks. In the depths of the Great Depression, voters decided to tax themselves to create the East Bay Regional Park District (EBRPD).

As we explore these 125,000 acres of parkland, we encounter some place names that are very old, offering a glimpse into earlier eras; others are of recent origin. Some names honor distinguished people—well known, like Judge John Sutter or Aurelia Reinhardt. Others, like Elsie Roemer and Es Anderson, are less celebrated, but have made their own important contributions to our parks. Some names recognize natural phenomena, like Big Break. Others recall aspects of human history—like the Angel Buggy Trail at Point Pinole.

With our wealth of natural beauty, even longtime residents have no shortage of opportunities to discover new parks, trails, and adventures. Even well-traveled parklands harbor historical secrets. As we celebrate the 85th anniversary of the park district, let’s look into how some of these places and features got their names. In some cases, the origins are well documented; for others the story is more obscure, inviting us to dive into surprising stores of information.

Judge John Sutter Regional Shoreline

OPENING IN 2020

The district’s newest regional park, the Judge John Sutter Regional Shoreline, is projected to open in spring 2020, offering public access to a sliver of sandy shore immediately south of the Bay Bridge and a look into the region’s transportation history. The new 45-acre park will connect with Radio Beach, where broadcast antennas line the north side of the bridge. Several remnants of the original Bay Bridge structural footings have been preserved and now anchor an observation pier that will be completed this year.

At the heart of the park is the Bridge Yard Building, a historic streetcar maintenance structure now restored into an event center. The long, narrow industrial building has a distinctive sawtooth roof and a west-facing wall of windows where more than 5,000 panes of glass were replaced with shatterproof material that can withstand earthquakes. The light-filled interior is quiet. Interpretive panels chronicle the history of the Interurban Electric Railway Bridge Yard Shop since its construction in the late 1930s.

The Bridge Yard Shop serviced streetcars from multiple transit companies that carried passengers across the lower deck of the San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge. Among those transit companies was the Interurban Electric Railway (IER), hence the maintenance building’s name. During World War II, one transit system’s ridership increased from 11 million in 1941 to 36.4 million in 1945 but its popularity was short-lived: as automobile ownership caught on after the war, streetcar ridership declined.

Following its restoration, the Bridge Yard Building has become eligible for the National Register of Historic Places, and the project won the Outstanding Historical Renovation Project Award from the San Francisco Section of the American Society of Civil Engineers in 2017.

The parklands surrounding the Bridge Yard Building intermingle with current and former industrial-use areas and are named for the honorable Judge John Sutter, a well-known regional park district director and longtime advocate for environmental stewardship and public access to open space. The shoreline park will be completed in phases, and the first piece is the Bridge Yard Building.

Sutter is an Oakland resident who graduated from Oakland High School, Harvard, and Stanford Law School. Following military service, he served as the Alameda County district attorney. In 1961, he worked to save Oakland’s Snow Park and helped found the group today known as Greenbelt Alliance. While on the Oakland City Council in the 1970s, he helped lead the effort that stopped the proposed Shepherd Canyon Freeway. He chaired the committee that prevented large trucks from operating on I-580, the MacArthur Freeway, through the Oakland hills.

Long before he was elected to the EBRPD board of directors in 1996, where he served for 20 years, Sutter advocated for the East Bay shoreline. He forged community alliances against filling San Leandro Bay. He helped to preserve the 741 acres that have become the Martin Luther King Regional Shoreline, an area not far from the shore park that now bears his name.

Dotson Family Marsh, Point Pinole Regional Shoreline

NAMED IN 2017

Born in Seaport, where the Richmond Field Station now stands, Whitney Dotson has always lived within arm’s reach of open spaces. But when his family moved north of Seaport about six miles to a brand-new community near the Point Pinole peninsula in 1950, a whole wetland and shoreline lay at his doorstep.

The family’s chance to leave public housing and move into their own home in the planned neighborhood came after the war, when developer Fred Parr and his son Chester decided to create a bayside village that welcomed the black community of Richmond. Parr worked with the pastors of local churches to create Parchester Village, with streets named after ministers and about 400 homes. The family moved in when Dotson was five.

“As soon as I was old enough to enjoy it, we used to just explore it all day,” Dotson said about the wetlands in a 2015 oral history interview. “Sometimes we’d be gone all day picking blackberries, throwing rocks, just going down to the water.” His father, the Reverend Richard D. Dotson, was an avid fisherman who often took his children with him to catch perch and bass for dinner.

The younger Dotson remembers that one of the first proposals to develop the wetlands came in the ’70s. “They were trying to put a small airport on the Breuner Marsh, so my father organized the community through his work with the [Parchester Village] Neighborhood Council, to oppose the project,” Dotson says. Through council leadership and neighborhood support and participation, the community prevailed.

Several decades later Dotson, who had returned to Richmond to care for his aging parents, and the community again found plans afoot to develop the wetland. In 2000 new owners, Don Carr and Bay Area Wetlands LLC, had purchased the property and were entertaining a string of proposals.

“They [were] proposing to put up a light industrial complex that would have brought 6,000 automobile visits per day into this area…[It] would make Parchester a landlocked community,” Dotson explains. “That’s what motivated me to get involved, because I knew it would impact the quality and the aesthetic for the whole area, not just Parchester Village.” Like his father before him, the younger Dotson became chair of the Parchester Village Neighborhood Council.

The Sierra Club and numerous other local environmental organizations took an interest in the development controversy and allied themselves with local residents, and again the wetland was saved from development. EBRPD acquired Breuner Marsh through eminent domain in 2008, and the area became part of the Point Pinole Regional Shoreline. Dotson was elected to the park district board of directors the same year.

Following a multiyear restoration project, the 238-acre wetland was renamed Dotson Family Marsh, in 2017. It won the Excellence in Design: Park Planning award from the California Park and Recreation Society. The marsh is accessible by a 1.5-mile section of the San Francisco Bay Trail.

McLaughlin Eastshore State Park

NAMED IN 2012

The 8.5 miles of shoreline that make up the McLaughlin Eastshore State Park has been assembled piecemeal as a park since 1980. From the outset, parkland advocates envisioned an open shoreline extending from Oakland northward through Emeryville, Berkeley, and Albany and on through Point Isabel, Richmond, and Point Pinole. Restored salt marshes would surround the San Francisco Bay Trail.

The vision is well underway to becoming reality. After public agencies prevailed against private developers in a 1980 state Supreme Court decision, the district began acquiring parcels starting in 1992—Emeryville Crescent, part of Hoffman Marsh, and Albany Mudflats. In 1998, the Berkeley Meadow, a former landfill, became the heart of McLaughlin Eastshore State Park.

The park’s name is a tribute to the late Sylvia McLaughlin, who in 1961 co-founded the Save San Francisco Bay Association at a time when faculty wives (her husband was a UC Berkeley engineering professor and a Regents chair) typically did not work outside the home. Still, in Berkeley and beyond, energetic, educated women were an unpaid army who fought for community betterment. When it came to saving the Bay, their battles ended in victory.

Prior to the 1970s, San Francisco Bay shoreline saw over 80 percent of its tidal marshes and mudflats drained or filled. From their Berkeley home, Sylvia and her husband could see a large, ongoing landfill at the foot of University Avenue. At nearby Emeryville Crescent, raw sewage discharged into the Bay. McLaughlin partnered with Kay Kerr and Esther Gulick to advocate for its cleanup. They gathered representatives from every environmental organization they knew about. “We brought it to people’s attention,” McLaughlin recalled in a 2011 interview with the San Francisco Chronicle. The public face of the organization, the gregarious McLaughlin, who died in 2016, exercised her access to the halls of power. Ultimately, tens of thousands of people joined Save The Bay.

The Berkeley landfill was closed. The sewage leaks were stopped. Finally, after a 25-year campaign, the EBRPD and California State Parks dedicated the shoreline park in 2006 and renamed it in honor of McLaughlin in 2012.

Future evolution of the park will extend the Bay Trail west of the Golden Gate Fields racetrack. The Albany beach has been restored, with healthy salt marshes providing wildlife habitat.

Big Break Regional Shoreline

OPENED IN 2009

Big Break Regional Shoreline lies along the San Joaquin River near the town of Oakley, and here the public can experience the mighty Delta. Schoolchildren visit the Delta Science Center, adventurers explore the region by kayak, and just about anyone can meander along the shore with its tule and bulrushes and diverse bird population. Embedded in the park’s name is the complex change the region has undergone in the past 150 years.

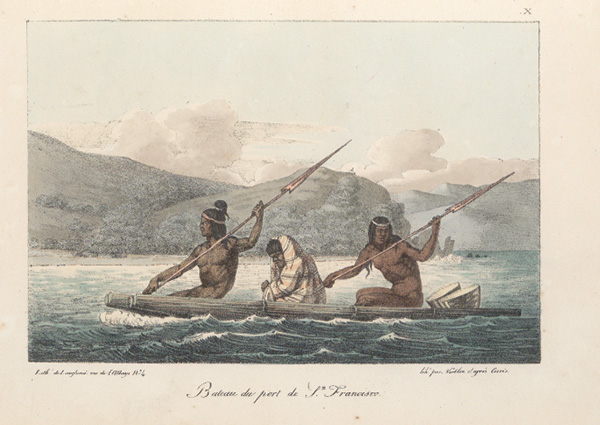

As the largest estuary system on the west coast of the Americas, the Sacramento–San Joaquin River Delta is where the fresh water from Sierra snowmelt mingles with the salt water of the Pacific. This giant wetland was once a superhighway for indigenous people to trade with neighboring tribes. Paddling their boats constructed from tule reeds, the Bay Miwok, Karkin, Yokuts, and neighboring peoples were surrounded by a bounty of food, including salmon and lamprey, geese and ducks.

The transformation of the great wetlands followed completion of the Transcontinental Railroad in 1869. Many who did this work emigrated from southern China, primarily from Guangdong and Fukien provinces, bringing experience from reclaiming farmland in the Pearl River Delta. Teams of horses drew scrapers that helped clear the ground of vegetation. Chinese workers are credited with inventing the “tule shoe,” which kept the horses from sinking in the mud. One of the first major land reclamation efforts occurred on Sherman Island beginning in 1968.

Earthen levees constructed along the streams within the freshwater marsh confined water flow to riverbeds, methods that helped create half a million acres of farmland with more than 1,000 miles of levees holding back the rivers today.

The “big break” occurred in 1927, when a major storm washed out a long section of levee, allowing the river to inundate a tract of asparagus farmland. Local farmers didn’t restore the levees and one might say that the river reclaimed the land, carving out the quiet bay that is now Big Break Regional Shoreline. Locals called the submerged tract “the Big Break” and the park district has kept the name.

Aurelia Reinhardt Grove, Redwood Regional Park

RE-NAMED IN 2002

When you walk along the tranquil Stream Trail in Redwood Regional Park in Oakland, you still see the foundation of the Little Church of the Wildwood, by Redwood Creek. The neighboring grove of redwoods here was officially dedicated in 2002 in honor of Aurelia Henry Reinhardt, a prominent educator, peace activist, and founding board member of the EBRPD.

“The entire [East Bay] redwood forest was originally named for Aurelia Reinhardt,” says EBRPD board member Dee Rosario. “In older maps, her name spans the area where the redwoods stand. Yet there was never an official sign put in the ground until 2002.”

Born in California in 1877, Reinhardt received her undergraduate degree in English literature from UC Berkeley and earned a Ph.D. from Yale University in 1905, both uncommon accomplishments for women at that time. Reinhardt also married and had children, but six years into the marriage her husband passed away, leaving her to raise two young boys. Sustaining her was an avid devotion to the Unitarian faith and a worldview that committed her to education and preservation of the natural world.

In 1916 Reinhardt became president of Mills College, a position she held for three decades and where her philosophy was to educate “a whole woman.” She urged Mills students to immerse themselves in nature and required them to walk at least one mile per day around the verdant campus.

She was also a strong advocate for conservation. She served on the EBRPD board of directors from 1934 until 1945, and her fellow board members recognized her as “a valuable aid…that extended in the acquisition and development of the East Bay Regional Park District.” Reinhardt also championed conserving California’s redwoods and was active in Save the Redwoods League.

In a speech she delivered at a redwood grove dedication ceremony in Humboldt Redwoods State Park in 1934, Reinhardt articulated her relationship to nature: “Shall we not dedicate ourselves to an understanding, to an appreciation of the life-giving qualities of the earth, our mother, and to a consecration of ourselves never to abuse, never to destroy, never to make barren, the fertile fields of our planet, Earth? Rather shall we respect and preserve, saving for our children and our children’s children the largesse of nature whose fruition man may destroy, but the secret of whose life is not yet in his childish hand.”

Es Anderson Equestrian Camp, Tilden Regional Park

NAMED IN 2000

The district has a long equestrian history, reflected in its four campgrounds designated for those overnighting with horses. In Tilden Regional Park, the Es Anderson Equestrian Campground sits at the foot of the majestic Seaview Trail, which connects to the Sibley Regional Volcanic Preserve.

The campground commemorates Esperance Anderson, best known as a horsewoman and advocate for equestrian trails, but she and her husband, Jock, were also native plant enthusiasts; she was a volunteer at the Regional Parks Botanic Garden.

Es and her family created a thriving native garden that included California lilac and manzanita and currants and sage, along with a large flannelbush at the intersection of the Selby Trail, the golf course, and Shasta Road in Tilden. Her friends from the Regional Parks Botanic Garden nicknamed the garden “Anderson Hill.” She also supported the planting of a butterfly garden in the Tilden Nature Area.

Anderson was on the forefront of change in Tilden Park. As the number of park visitors grew, suddenly horses were not welcome everywhere.

Since 1968 Anderson had been part of the East Bay Area Trails Council, an innovative forum that brought hikers, mountain bikers, and equestrians together. “The aim was not only to develop new trails, but also to work out trail compatibility,” Anderson wrote in 1993.

Tilden-Wildcat Horsemen’s Association, established around 1973 with Anderson as a founding member, soon followed. The group continues today to work collaboratively with other park users, holding events and work parties to improve trails. After Anderson’s death in 2000, the park district officially named the group campsite in her honor.

Elsie Roemer Bird Sanctuary, Robert Crown Memorial State Beach

NAMED IN 1979

Stand on the dock in the Elsie Roemer Bird Sanctuary overlooking the Bay from Alameda, and depending on the time of year and the tide, you can observe tens of thousands of migratory birds traveling the Pacific Flyway. Birds that can be frequently spotted there include marbled godwits, killdeer, long-billed curlews, dunlin, dowitchers, and dozens of other species. A colony of federally threatened Western snowy plovers has chosen this eastern end of Crown Memorial Beach for its winter nesting ground.

This is all thanks in part to Alameda resident Elsie Roemer, who had a deep love for nature. Roemer and her friend Junea Kelly, both members of the Audubon Society, enjoyed observing birds on the mudflats of Alameda. Eventually, biologists from the then state Department of Fish and Game asked the Alameda birder group to share the bird counts they were compiling. The group continued to regularly provide data.

“The Alameda birders were dedicated. They loved their mudflats,” recalls Leora Feeney, who joined the group in 1974 and is known for her work preserving wildlife habitat, particularly at the former Alameda Naval Air Station.

Today’s South Shore of Alameda, with homes and stores looking out over Crown Memorial State Beach, was created from fill dredged up from the bottom of the Bay by Utah Construction Company in the 1950s. Twenty years later, cordgrass and pickleweed began to grow along the disturbed shorelines. Roemer observed that rare clapper rails had begun to nest there. “Elsie loved all the rails, but especially the noisy clapper rail—now called Ridgway’s rail,” Feeney recalls. “They seemed to echo our chattering at the edge of their home. It always brought delight and big smiles.” In 1979, Elsie Roemer’s friends asked the park district to create a bird sanctuary and name it after her.

Another campaign for shorebird habitat began at Arrowhead Marsh, near the Oakland Airport, in the early 1980s. Roemer, peering through a chain-link fence, had observed a population of rare California least terns there. She took particular note when the Port of Oakland began to fill a seasonal wetland at the site.

“[Elsie] stood shaking her fist at the bulldozers and shouting strong language—wise words, not profanities, as she was a refined woman,” Feeney recalled in a KQED interview. “She was a quiet and gentle person, but she could get mad sometimes.”

In 1986, the Golden Gate Audubon Society, along with Save the Bay, sued the Port of Oakland to preserve the bird habitat at Arrowhead Marsh. In 1994, the suit was settled. According to the Golden Gate Audubon Society, the settlement “left the remaining seasonal wetlands untouched, restored 72 acres of tidal and seasonal wetlands in San Leandro Bay, and deeded the restored wetlands to the East Bay Regional Park District to complete the Martin Luther King, Jr. Regional Shoreline Park.”

While the federally listed Western snowy plovers are overwintering from approximately end of September to early April, protective fencing and signage is installed on portions of the beach where they reside. Roemer, who passed away in 1991 at age 99, would approve.

Angel Buggy Trail, Point Pinole Regional Shoreline

OPENED IN 1973

The tranquility of Point Pinole Regional Shoreline, the 2,315-acre park that juts into San Pablo Bay in Richmond, belies its explosive past.

Four companies manufactured gunpowder, nitroglycerine, and dynamite here while they owned the peninsula between 1880 and 1960. When the district opened the park in 1973, it named several trails after the volatile businesses.

Today the park’s 0.15-mile-long Nitro Trail refers to the Safety Nitro Powder Company, established in 1881. The 0.28-mile Giant Station Trail is a nod toward the train station that served the companies and residents in the area. The Giant Powder Company, which produced nitroglycerine there starting in 1892, had dozens of small buildings connected by a narrow-gauge train. Dense rows of eucalyptus trees were planted from 1921 to 1922 as a blast shield.

In the early 1900s, Atlas Powder Company replaced the Giant company in the facility, becoming a major munitions supplier during both World Wars I and II. Along what’s now called the Angel Buggy Trail, workers wheeled lead-lined handcarts, filled with nitroglycerine, from the neutralizer to the “mix house.” Employees nicknamed the carts “angel buggies” because sometimes they blew up, killing workers.

Vollmer Peak, Tilden Regional Park

NAMED IN 1938

At 1,905 feet, with views of the Bay and surrounding hills, Vollmer Peak is the highest point in Tilden Regional Park near Berkeley. It is known for its good birding and abundant butterflies. Perhaps less well known is the man it was named after, on March 26, 1938.

August Vollmer, considered by many the father of police professionalism, began his public service career in the 1890s by helping organize the volunteer North Berkeley Fire Department. Then, after returning from service in the Spanish-American War in 1900, he stopped a runaway construction flatcar from hitting a commuter train on Shattuck Avenue. The act of heroism propelled him to electoral victory as Berkeley marshal. Following the 1906 earthquake, Vollmer deputized local war veterans to keep the peace in a town suddenly overflowing with refugees. In 1909, he was named the city’s first police chief.

An innovator, Vollmer deployed officers in cars with radios and on motorcycles, when those practices were new ideas. Shortly after the “lie detector” was invented at UC Berkeley, Vollmer’s department adopted it in 1921. He encouraged officers to earn a college degree and started a department of criminology at UC Berkeley, of which he became chair in 1916.

After retiring from police work in 1932, Vollmer became active in the community group that was working to form the EBRPD and was on the founding board of directors.

French Trail, Redwood Regional Park

OPENED IN 1937

Even in 1937, when the park district had just opened the long swatch of hills and valleys of Redwood Regional Park to the public, the French Trail was regarded as historic. It gradually descends over roughly four miles from the park’s West Ridge, curving along the steep side of the canyon, ending at the Orchard picnic area.

The trail’s namesake, Harold French, was inspired by John Muir. Though there is no evidence that the two men met, French named his children John Muir French and Muriel French in the naturalist’s honor. French, also a member of the Sierra Club, founded his own local hiking and conservation group, the Contra Costa Hills Club, in 1920.

Beginning around 1909, French wrote articles for the San Francisco Call, the San Francisco Daily Post, and other publications. He exhorted the public to pack their knapsacks, board the trolley car or the ferryboat, and “tramp” into the wilds of Mount Tamalpais, Mount Diablo, or the Oakland hills.

French was also a fierce advocate for the creation of the park district. In a resolution dated November 18, 1936, Jesse K. Brown of the Tamalpais Conservation Club chastised Major Charles Lee Tilden for having failed to recognize French in the new park district’s opening ceremonies the month before.

“Harold French was the first to think of establishing the park,” Brown wrote. “For 17 years, he planned and worked for it…(F)inally, after discouragements and rebuffs that would have disheartened any man not sustained by lofty ideals, he won!”

Members of the Contra Costa Hills Club proposed naming a trail after their founder. They chose a trail that Tony Alameda, a longtime resident of the area, showed them, telling them his family had used the trail for generations, according to an Oakland Tribune article. In 1937 the club members completed clearing the “old horse and buggy road” that would become the French Trail in Redwood Regional Park.