From the Napa Valley town of St. Helena, Spring Mountain Road describes a steep and tortuous route up the eastern slope of the Mayacamas Range. It’s not wise to take your eyes off the road, yet you can’t help but admire the scenery. Off to your left is Spring Creek gorge, heavily forested with redwood and Douglas-fir. As you climb into the higher elevations, pocket vineyards appear, tucked among the conifers and groves of madrones.

Where a narrow side-road veers to the south, Jonathan Koehler, the guide of this tour and the senior biologist for the Napa County Resource Conservation District, gives the steering wheel of his Jeep Cherokee an easy flick and we’re off the main highway. We drive past a terraced vineyard, then penetrate a heavy growth of young Doug-firs still in the Christmas tree stage.

Suddenly we break into the open, and a spectacular vista unfolds. It is haunting, almost Arcadian in its loveliness: a rugged topography of peaks and slopes, rolling meadows, vineyards, and woodlands. At this time of year–midwinter–everything is deeply green, green in all its hues and registers, from almost incandescent emerald grasses to deep viridian forests. Koehler stops his rig and we get out. Stuart Weiss, the chief scientist of the Creekside Center for Earth Observation in Menlo Park, emerges from the back seat. Directly below, a small stock pond glimmers through a stand of oaks. Chorus frogs are vocalizing all around us, and a couple of turkey vultures fly overhead.

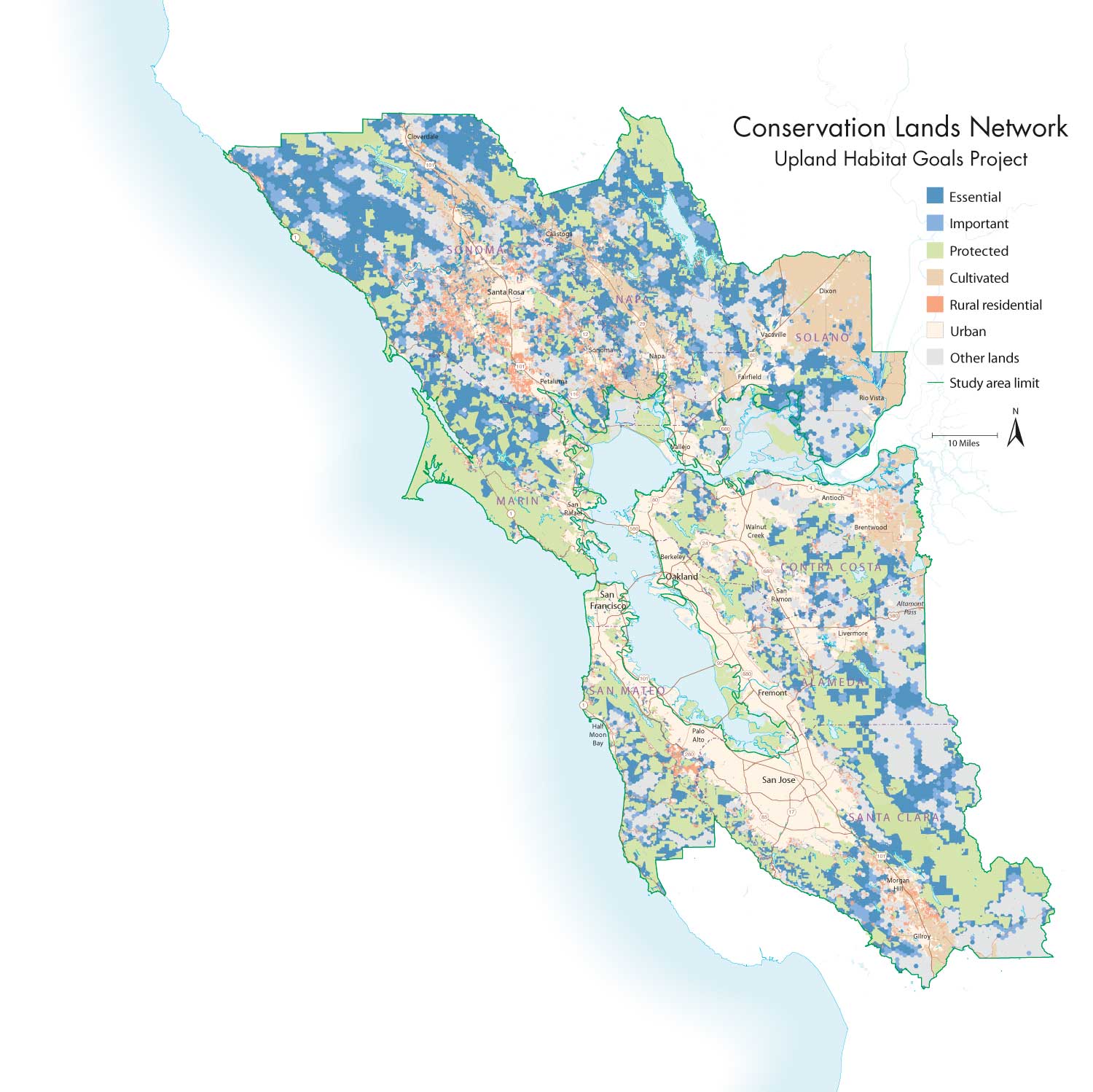

It occurs to me that we may be looking at this landscape from strikingly different perspectives. I’m simply drinking in its beauty. But Koehler and Weiss are likely seeing not just a tableau of rills, rocks, trees, grassy leas, and vineyards. Layered over that, they’re probably seeing blue hexagons marching across the land. Not because they’ve imbibed some exotic hallucinogen: Rather, they have been instrumental in the creation of a remarkable dataset and computer model that balances hundreds of variables to calculate the best possible network of undeveloped lands for preserving the Bay Area’s biodiversity. As part of the ambitious Upland Habitat Goals Project (UHG), the entire 4.26 million terrestrial acres that comprise our region’s nine counties have been divided into 100-hectare hexagons (247 acres), each color-coded for its significance to native flora and fauna, with the most important ones colored in various shades of blue. A variety of factors influence the coding, from the quality of the habitat to contiguity with protected lands. The UHG Project’s objective is the creation of a detailed picture of a new Conservation Lands Network (CLN). Starting with the region’s existing protected lands, the goal is to identify additional areas–primarily private lands–that harbor high biodiversity in need of conservation.

- Panorama looking southwest over the Napa Valley from Robert Louis Stevenson State Park. Napa and Sonoma counties contain undeveloped lands critical to Bay Area biodiversity. Photo by Ian Creelman, circleoflightphotography.com.

A deep sense of urgency is driving this effort. Prime conservation lands are at extreme risk. The Bay Area, after all, is one of the most heavily populated regions in the country. At the southern end of the Napa Valley, the city of American Canyon is bursting at the seams, melding with Vallejo and the sprawling megalopolis that characterizes the East Bay. Farther north, the vineyards are creeping up from the valley floor to the surrounding hills. And wherever open space falls to urban development or intensive agriculture, habitat is invariably fragmented and biodiversity degraded.

The project therefore attempts to identify and plot the Bay Area’s remaining biodiversity, with an eye to long-term conservation. This five-year venture is spearheaded by the Bay Area Open Space Council and supported by a large number of public agencies, private foundations, conservationists, private landowners, land trusts, and local universities. More than 80 scientists and land managers helped refine goals and conservation targets.

- This map shows the proposed Conservation Lands Network. Open a larger version. Map by Louis Jaffe / GreenInfo Network, greeninfo.org.

The project could be considered a logical follow-up to the landmark San Francisco Baylands Ecosystem Habitat Goals project. A decade ago that initiative drove the protection and restoration of thousands of acres of marshland around San Francisco Bay. The UHG Project is also a cousin of the San Francisco Bay Subtidal Habitat Goals Project (profiled in Bay Nature in fall 2010).

“In many ways, though, this is more challenging,” says Weiss. “Uplands are typically much more complex than baylands. The biodiversity is richer, and the terrain is fragmented. Connecting the parts to achieve conservation goals is harder. Plus, the uplands feed the baylands–what happens in the upper Napa River watershed affects San Pablo Bay.”

If the basic idea is simple–plot a series of data overlays on a map to create a comprehensive picture of what lives where–the work was challenging. Even in a circumscribed and heavily urbanized region, nature exists on a deep and fractal level. How can you possibly identify species of concern on a landscape scale and present them in a useful and accurate format? The answer, of course, is by garnering all the available data and putting in the necessary hours.

Top Priority: Save the Streams

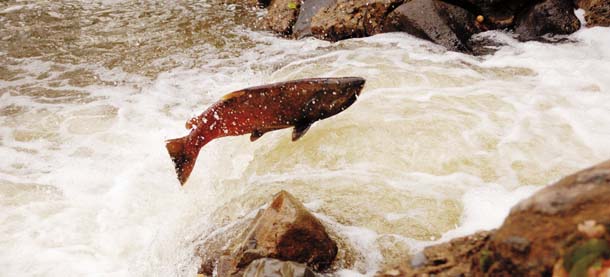

- Chinook salmon in the Napa River. Photo by Lowell Downey, artclarity.com.

Koehler devoted a lot of the sweat equity to this project–both directly as an adviser on riparian issues, and indirectly through his work as a fisheries biologist for the Napa County Resource Conservation District. Indeed, the research produced by Koehler, U.S. EPA ecologist Rob Leidy, and other scientists underlines a major emphasis of the UHG process: Streams–all streams–are a top conservation priority for the region.

“Streams provide fundamental ecological connections through the landscape,” says Weiss. “Riparian zones always contain unique local habitats, rich habitats. They’re fragile–it’s easy to trash them. But we’re also learning how to restore them.”

The Napa River is a powerful metaphor for the great ecological value of riparian areas. It’s not just about wine country public relations and the millions of tourists the valley draws each year. The Napa system is also unexpectedly rich with native fish. Koehler has demonstrated this over the past few years by operating a trap that captures samples of the river’s juvenile fish. One of the earliest revelations was that the Napa River supports a relatively robust population of fall-run chinook salmon.

“We didn’t anticipate that,” Koehler says. “We also found that the steelhead run was quite strong. And then there were all the other species–some completely unexpected.” That included sockeye salmon, which no one imagined were spawning in the river. Koehler thinks the sockeye descended from kokanee salmon, a landlocked sockeye variant, that were planted in nearby reservoirs.

Even more compelling from a conservation point of view is the presence of other fish–less glamorous species that are linchpins of local aquatic ecosystems. Koehler has recorded more than 25 species of fish, including California endemics such as hitch, hardhead, Sacramento sucker, Sacramento blackfish, and pike minnow.

- Jonathan Koehler, here holding a western pond turtle, has shown that the Napa River watershed is remarkably rich in native fish, including chinook salmon. Photo by Chad Edwards.

“It’s really amazing,” says Weiss. “Despite all the impacts from development and viticulture, the Napa River is one of the crown jewels of native fish habitat for the Bay Area.” Weiss ruminates for a minute, and then continues. “You know, what we’re doing really comes back to that Aldo Leopold quote–‘The first principle of intelligent tinkering is to save all the parts.’ The Upland Habitat Goals process is allowing us to identify and save the pieces.” When those pieces come together in the Conservation Lands Network, Weiss hopes, effective conservation strategies will emerge.

Already, those strategies are taking shape. The Napa River’s impressive biodiversity appears to be a recent phenomenon–a matter of resuscitation rather than long-term stability. By the 1980s, the river had become a sump, a sluggish canal clogged with sediment sluiced from adjacent vineyards. Tough water quality control regulations and private riparian restoration initiatives–most notably those undertaken by the vintners of the Rutherford Dust Society–are helping to bring the river back.

“Preserving biodiversity is largely a matter of preserving habitat,” says Koehler. “With the Napa River, a variety of factors are involved–and foremost among them is stabilizing the upper watershed. If the upper watershed isn’t stable, sedimentation will hammer the fish.”

Biodiversity on the Range

- View from Roger’s Ridge in Morgan Territory Regional Preserve near Mount Diablo. Photo by Scott Hein, heinphoto.com.

The significance of riparian zones is rather intuitive–water, fish, and lush streamside forests all speak eloquently of wildlife and healthy ecosystems. Not so obvious, perhaps, is the importance of another habitat, one conservationists value as highly as streams: grasslands.

There’s a lot of rangeland left in the Bay Area–about 1.7 million acres. That fact alone makes grasslands an essential component in conservation planning. But all that open space is more than simply open space.

“On the one hand, grasslands are among the most modified habitats we have in the Bay Area,” Weiss says. “Invasive plants are a huge problem. But grasslands also support tremendous biodiversity. They contain a mosaic of habitats and species–oak woodlands, native bunchgrasses, vernal pools, wildflower stands, ponds with red-legged frogs and California tiger salamanders, serpentine soils with endemic flora, burrowing owls, badgers, even tule elk. No matter how you look at it, we’re going to have to conserve and manage grasslands if we’re going to preserve biodiversity in the Bay Area.”

Which gets back to the issue of implementing the Conservation Lands Network: Providing productive wildlife habitat means identifying properties for conservation and establishing corridors between protected parcels. Getting that done on a large scale requires voluntary participation even more than regulation and public acquisition of land. Most Bay Area grasslands are privately owned and destined to stay that way, so conserving the biodiversity on these lands means working cooperatively with the owners–ranchers, in most cases.

“Not everything has to be purchased outright by public agencies or nonprofits,” says Nancy Schaefer, UHG Project manager. “Protection through conservation easements and voluntary stewardship incentives can be preferable for a number of reasons.”

The first is cost. Permanent easements–agreements in which landowners forgo development and conform to specific land management regimens in exchange for cash payments–are generally much cheaper than outright acquisition and often include ambitious restoration programs.

“Even when the state has been able to acquire land for conservation purposes, there hasn’t always been funding available for critical stewardship,” Schaefer says. “In most cases, active land management is necessary to both improve and maintain biodiversity: fencing streams, keeping invasive weeds in check, even using cattle to reduce heavy grass thatch and help plants that native butterflies need.” Conservation easements also keep ranchers on their ranches and their properties on the tax rolls. “Ranchers are the community in many rural areas,” she says. “They are also stewards of the lands under easement–their active participation is necessary for the implementation of conservation measures.”

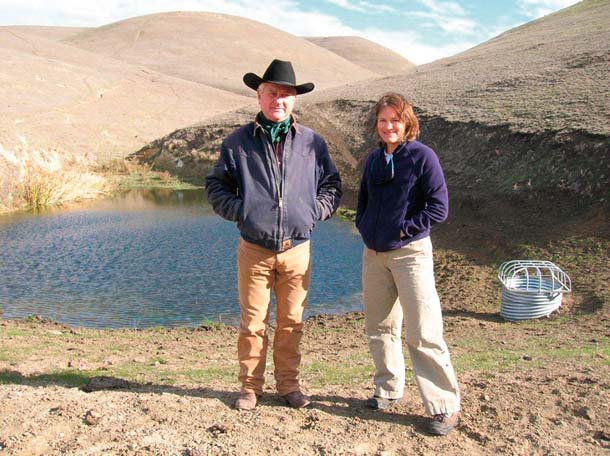

- Rancher Darrel Sweet with Kate Symonds of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in front of a stock pond that was re-engineered to benefit California tiger salamanders and red-legged frogs. The cost of the work was shared by Sweet, Fish and Wildlife, and a number of other agencies. Photo courtesy USFWS.

It is unlikely anyone exemplifies Schaefer’s definition of the rancher-cum-steward better than Darrel Sweet, a fifth-generation cattleman who lives on his 1,000-acre ancestral ranch at the summit of the Altamont Pass in eastern Alameda County. I meet Sweet one clammy, cold afternoon at his driveway along North Flynn Road.

A past president of the California Cattlemen’s Association, Sweet is a cheerful, bluff, sixtyish man of middle height, clad in the rancher’s uniform: jeans, worn work jacket, battered Stetson, and cowboy boots designed for actually riding horses rather than line-dancing in the local C&W bar. He’s a tad sore on the day of my visit: A testy horse kicked him in the left kidney a month earlier, and he’s still recovering. This doesn’t detract from his enthusiasm, however: for his grandkids, for the history of the Altamont region, for the cattle business, and for ranchers’ role in the CLN.

We clamber aboard a battered ATV and churn through the fog and hills. Ground squirrels whistle in alarm and scramble out of our way. After 10 teeth-chattering minutes, we drop down a slope to a small, muddy pond. Cattails crowd one end, and all of it is fenced to exclude cattle except for a single narrow ingress point. It isn’t pretty, but this homely little stock pond is critical habitat for two of the Bay Area’s most beleaguered animals: California tiger salamanders and red-legged frogs.

“It turns out that stock ponds are hot spots for both species,” Sweet says. “In many areas, it’s the only good habitat they have. But the ponds have to be managed in a certain way.”

- A suburban development in Dublin encroaches on the open grasslands. Photo (c) Barrie Rokeach 2010, rokeachphoto.com.

Built in the 1960s, Sweet’s pond was considered temporary, with a dirt spillway likely to wash out over time. Now, an overflow pipe and fencing ensure it will remain good amphibian habitat. But the salamanders also need uplands, where they hole up in squirrel burrows. “It doesn’t fit the usual stereotypes of ‘prime’ wildlife habitat,” Sweet observes. “But it’s what the salamanders need. As long as we give it to them, they do fine.” The Sweet family covered about 10 percent of the $35,000 cost of the improvements. State and federal agencies paid the rest, and the Alameda County Resource Conservation District supervised the work.

Ranchers can also secure permanent conservation easements on their entire properties. “They’re not for everyone,” Sweet acknowledges. “But in the right situations, they can work out well for both ranchers and wildlife.” With an easement, owners can realize $7,000 to $10,000 an acre in one-time payments in return for taking specific restoration measures and restricting land use and stocking levels.

“People still get to graze their cattle,” Sweet says. “Grazing is usually part of any management plan, particularly for red-legged frogs and tiger salamanders. So you have endangered amphibians going from a potential liability to an asset.”

In eastern Alameda County, it’s not just about amphibians. The range of the San Joaquin kit fox, one of the hemisphere’s rarest canids, reaches the Altamont. Home to the world’s densest population of golden eagles, it’s also a critical migratory corridor for other raptors. Conserving habitat for all these species–as well as for water quality and open space–puts ranchers at the forefront of Bay Area conservation.

- The lands around the Altamont Pass, including thousands of acres of working ranchland, are prime hunting grounds for golden eagles. Photo by Matthew Polvorosa Kline, polvorosaklinephotography.com.

New digital tools will help get this work done on the ground. “A guy can go on [the CLN website, bayarealands.org] and see how his property stacks up in terms of priority species, location in regard to other high-value properties, all kinds of factors,” Sweet says. “More and more ranchers want in on this. A few years ago, they resisted it. Now they see it as the thing that will let them stay on their land.”

He points out a golden eagle cruising the ridgeline above us, no doubt hunting ground squirrels. “I was with my little grandson not long ago, and we were watching a bald eagle flying around,” he says. “Suddenly he turned to me and said, ‘Grandpa, this is so great. No other kids I know get to live on a ranch and watch eagles like we do.’ He intuitively understood what we’re doing here–and that made me feel pretty good.”

Networked Conservation

Don Rocha, the natural resource supervisor for the Santa Clara County Parks District, says the Conservation Lands Network has taken land managers “out of our bubbles. We’re communicating now in a way we never could before, and our data is easily shared. That’s really making a difference in regional planning, the heart of effective conservation. We have to treat the Bay Area as a whole if we’re going to make real progress.”

- Cows on Coyote Ridge southeast of San Jose. Managed grazing has proven essential for maintaining native plant diversity on serpentine soils. Photo by Stuart Weiss, creeksidescience.com.

Rocha oversees natural resource issues on 45,000 acres of parkland, and a big part of his job revolves around preserving biodiversity. This is a particular challenge in the South Bay, where decades of urbanization have fragmented habitat. The CLN is new and hasn’t been deeply integrated in Santa Clara County Parks policy, but he anticipates that will change. “We think these new layers of information will be especially helpful in identifying land acquisition priorities,” Rocha says. “It’ll allow us to look at habitats on a regional scale.”

The data should also help park managers with the sensitive task of balancing public access with biodiversity protection. “The taxpayers are supporting these parks, and they want to be able to use them,” Rocha observes. “But our mandate also includes resource protection, so we hope to use the CLN to help us do both. We can see what is where, figure out the best trail routes, and plot buffer areas and protected zones.”

The CLN’s online tools include biodiversity reports–specific information on vegetation types (roughly 50 categories), listed species, and geographic features. “You delineate an area and out pop the different vegetation types, the number of ponds and streams and listed species,” Weiss says. “You’re able to see how any particular parcel fits into–or doesn’t fit into–the Conservation Lands Network.”

The Conservation Lands Network is the heart of the project, says Weiss: “That’s what we’re emphasizing–the integrity of the network, not the individual parcels. Everything must be viewed from this larger perspective.”

The digital tools informing that perspective are grounded in free planning software called Marxan, which allows scientists to devise conservation strategies incorporating hundreds of biodiversity targets and thousands of candidate areas.

“You can establish goals and design inputs about the conservation value of the planning units–human population density and distance to roads, for example,” says Ryan Branciforte, the Open Space Council’s director of conservation planning.

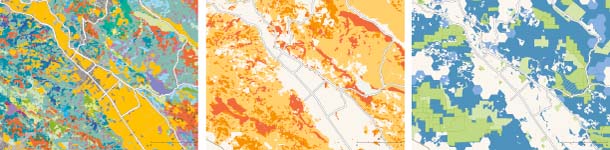

- The Conservation Lands Network relies on extensive mapped data, as in this Napa Valley section: Vegetation types (left) are combined with rarity (center), conservation targets, and other measures such as distance to roads to produce the optimal Conservation Lands Network (right, in green and blue). Map by Louis Jaffe / GreenInfo Network, greeninfo.org.

The project’s website (bayarealands.org) hosts detailed geographic data for scientists and land managers, as well as an online interactive version, called the Explorer, that allows anyone to mix and match overlays–laying vegetation rarity over existing protected lands, for example. In graphic form, the message of the blue hexagons is clear in a way that words could never match; it is immediately obvious where the priority lands lie.

“There is probably more GIS spatial data available on the nine Bay Area counties than on any other region on the planet,” says Branciforte. “And it’s very good data. A lot of very intelligent people have been working on this for a long time– decades, really. We had a huge database to work from.”

All that data helped determine which of the 17,225 hexagons in the CLN map were “best” for conservation, as determined by everything from vegetation type to the presence of endangered and threatened species, contiguity with already protected parcels, and migration corridor potential.

- California poppies frame this view from Mount Diablo. This mix of grasslands and oak woodlands is critical habitat for hundreds of species, from wildflowers to tiger salamanders to burrowing owls. Photo by John W. Wall, jwallphoto.blogspot.com.

“It tells you where the priorities are,” Branciforte says. “That doesn’t mean a hexagon doesn’t have any biodiversity value just because it’s not blue. Any acreage we get–blue or not–will probably still contribute to achieving upland habitat goals. But the blue hexagons should be considered first.”

Establishing priorities is a matter of deep concern for Gary Knoblock, Bay Area program officer for the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, a key CLN funder and the nation’s largest private financial supporter of environmental initiatives. “These are tough economic times,” Knoblock says, “and we are not immune to them. [The CLN project] is helping us make the smartest investments possible. The map overlays give you the regional perspective to make tough decisions.”

Still, the map is more a reliable sketch than an exquisitely detailed portrait, and its resolution will improve over time as data is continually added to the overlays.

“I have a certain faith in the maps, but the Conservation Lands Network must change and evolve,” says Amy Hutzel, the state Coastal Conservancy’s Bay Area program manager. The CLN is designed to be flexible in the face of many factors–from climate change to shifts in a specific parcel’s protected status. That points to a larger truth: Preserving biodiversity is a marathon, not a sprint.

“Twenty years ago, the Napa River was a real mess,” says Weiss, as we luxuriate in our view of the upper Napa Valley. “But now we’re starting to see the payback from the work started then. We have pretty good steelhead and chinook runs, and a surprising number of other native fish inhabit the river. I anticipate it could take 30 to 50 years to really see the full benefits of the upland work we’re doing now. Conservation takes time as well as money and effort.”

And the right tools in the hands of the right people.

.jpg)