Most golf courses wouldn’t want to see, let alone encourage, the presence of ground-dwelling animals around their immaculately kept greens.

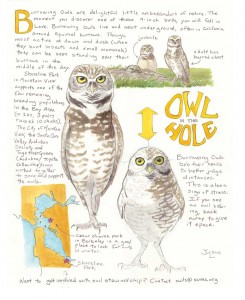

But Shoreline Golf Links in Mountain View is offering up habitat for burrowing owls in the hopes it can establish a healthy, year round population of the threatened bird, which makes its home in abandoned ground squirrel holes in grasslands and agricultural areas.

Maybe it’s because of their charm factor, but the burrowing owls have apparently become a bit of an attraction along the fairway.

“The golfers take photos, tell us where they’ve spotted them — some have even named the owls,” said Mountain View’s wildlife biologist Philip Higgins.

Burrowing owls are generally considered avian non grata in most development zones, where they are practically extirpated in the face of bulldozers. Consequently, the population has fallen steadily over the past 20 years to a few pockets of undeveloped grassland around the Bay Area. It’s listed as a Species of Special Concern by the state, but there is an effort to give it endangered species status.

Some landowners, notably the city of Mountain View, have taken to supporting the burrowing owls that remain. The golf course is a part of Shoreline Regional Wildlife Area, city-owned property situated alongside the massive Google and Intuit campuses, that is being maintained with the long-term goal of supporting 10 breeding pairs (right now there are 5 breeding pairs and four individuals).

“Mountain View has gone furthest to preserve and increase the burrowing owl population” in the South Bay, said Lynne Trulio, a burrowing owl expert and chair of the environmental studies department at San Jose State University.

The success of the burrowing owls in the heart of Silicon Valley can help prove a point that owl advocates have long made: burrowing owls are resilient and capable of living — even thriving — in cityscapes if we just make some room for them.

Burrowing owls are quite small — they weigh just 5.3 ounces. And unlike most owl species, they are often active during the daytime, especially in the spring when they are tasked with gathering food for their growing broods. Their diet includes anything smaller than them: small rodents, insects, birds, and even amphibians and reptiles.

At the Berkeley Marina, where the burrowing owls have caused quite a sensation in recent years, Shorebird Nature Center sets up protective fencing during overwintering months to keep people and dogs and bay.

Meanwhile, NASA Ames’ Moffett Airfield, near the Shoreline park in Mountain View, keeps the largest number of burrowing owls in the region — 22 breeding pairs — by maintaining 80 acres for their benefit.

In 2006, partially in response to increased public attention concerning the owls, airfield staff began incorporating the birds into the management of the property by using one-way doors to passively evict the owls from their burrows in restricted areas. The owls then find their way to one of the four preserves on airfield property that are made attractive to the birds by mowing the grass right before owl breeding season.

Airfield staff have also put up signs to watch out for low-flying birds, and trains staff before nesting season.

“NASA is committed to keeping our population of burrowing owls stable,” said Ann Clarke, assistant director of operations at for Moffett Airfield.

Unfortunately, the success stories are few and far between. At the California Burrowing Owl Consortium, a recent gathering in Mountain View of burrowing owl experts and advocates organized by the Santa Clara Valley Audubon Society, many expressed dismay of the overall lack of protection afforded to these birds.

Typically, a developer offsets burrowing owl habitat by buying land in a mitigation area, then evicts the hapless birds from the construction site. Usually, mitigation land is located far away, making it unlikely the owls will know the location of their reassignment. There’s little monitoring of what happens.

“In most areas, the owls have been mitigated to death — literally,” said Shani Kleinhaus, an environmental advocate for Santa Clara Valley Audubon Society.

Sometimes they are evicted from their burrows with one-way doors. The owls will usually stand outside the closed-off burrows for the rest of the day, if not longer, which leaves them vulnerable to predators like hawks, foxes, dogs and cats. Other times deadly smoke bombs are tossed into the dens, or the land is simply ploughed over- burrows, owls, and all. Such practices are illegal under the Federal Migratory Bird Act, but they still happen.

“There’s barely any accountability or oversight when it comes to burrowing owls being ‘in the way’ of development,” said Scott Artis, founder of the Burrowing Owl Conservation Network, which has an office in Berkeley.

Lynne Trulio, the burrowing owl expert, said most public officials put the needs of burrowing owls on the back burner, as they do other species.

“Most cities haven’t done enough to integrate wildlife protection into their sustainability plans,” said Trulio. “We should be able to achieve that, but as it stands our culture still doesn’t consider it an obligation to include other species in land use planning.”

Mountain View may be the rare exception.

“Pressure from Santa Clara Valley Audubon Society has been a big factor, as well as city planners working for Mountain View who are interested in protecting the owl,” said Trulio. “But the biggest piece has been city council members — you can have all the other pieces, but if you don’t have the city on board it won’t work.”

Shoreline Regional Wildlife Area has its complications, as far as burrowing owl habitat. It’s a

former landfill, and landfill supervisors typically get nervous when burrowing animals make their homes atop trash graveyards. But Shoreline has found ways to accommodate the owls. It helps that the landfill cap is far enough below the surface that the burrows do not risk disturbing the cap’s integrity.

“Certain techniques we use to maintain the nesting habitat actually helps [the landfill managers] do their job,” said Higgins, the Mountain View biologist. “Also, we’re all outside monitoring the area, so we tell the landfill people where we see cracks and they tell us where they see burrowing owls.”

The techniques work for Mountain View, and perhaps with a bit of creativity and more concern, other communities can find ways to welcome in this tiny and quizzical creature.

Constance Taylor is a Bay Nature editorial intern.

-300x221.jpg)

-300x200.jpg)