“We reached the old wolf in time to watch a fierce green fire dying in her eyes. I realized then and have known ever since that there was something new to me in those eyes, something known only to her and to the mountain.”

— Aldo Leopold, A Sand County Almanac

BN: Are you a Bay Area Native?

Kitchell: I arrived at the age of three. You have to decide.

BN: Do you feel like a Bay Area native?

Kitchell: Very much so. The first thing I remember is the train coming west from New Hampshire. I recall going through the Painted Desert at night, lying on my bed and looking out the window at the moonlit landscape. My parents were both architects, and they both were involved in local environmental issues. Now I live about a mile from where I grew up in Bolinas.

BN: How did you become a filmmaker?

Kitchell: I come from a family of artists; my older brother is a very fine visual artist. I couldn’t compete with him that way, so I took up the ultimate art form of my time — photography. Some friends and I had put on an early light show. I had had some psychedelic visions, and I thought there was great potential to recreate some inner states of consciousness using these artistic techniques.

BN: What was the next step? How did you become a documentary filmmaker?

Kitchell: I fell in love with the documentary in New York City. I had attended one quarter at UCSC, but then I dropped out and went to NYU, where I earned a BA in Film in 1976. I was living on the Lower East Side and they used my block to make Godfather II. The whole neighborhood got caught up in the film. I began to make a documentary about the making of the film and got Coppola’s permission to film on the set. My film was called The Godfather Comes to Sixth Street.

BN: How did you become an environmental filmmaker?

Kitchell: I was trying to do something revolutionary in the world. And my wife said I ought to do a history of the environmental movement. I went to see Neil Wilson, a biologist and an advisor to the film. He said, the topic is extraordinarily broad. I want you to pick five of the most dramatic important events or people in the history of the environmental movement. Here was this eminent biologist telling me that I had to follow all the rules of traditional drama and storytelling.

So I picked: David Brower vis-à-vis Sierra Club and Grand Canyon; Lois Gibbs, Love Canal and toxic waste; Paul Watson, Greenpeace, Whales; Chico Mendez, rubber tappers and the Amazon rain forest; and global warming.

Temporarily out of money, I had to put aside the project for a few years. In the meantime, each of the people became a story, and a chapter in the movie. The Grand Canyon became the conservation movement. Greenpeace became the ecology movement. And so on.

The section about climate change broke form a bit. I wish we could have gone on to Chapter 6, Civilizational Transformation. This is what the environmental movement is really all about. We have to reinvent our modern industrial society, and our capitalist model based on limitless growth.

When I make a film, I think about what the main “take-away” is, and civilizational transformation is what it’s all about. However, the term is very vague. When I met with Meryl Streep, who narrated one of the sections, she instead used words that said something like, “changing the way we make and do everything and also the way we think about ourselves.”

BN: What was the most difficult part of the process of making the film?

Kitchell: “Killing your babies”, that is, editing and condensing the material. Near the end of the process, you have all of this good stuff and some of it has to come out. For the broadcast version, at first they said we could have two hours, but then it had to come down to one hour. I was amazed that we could do it. Thank God for editors.

I didn’t really know if it was truth or a fiction that there is just “one” environmental movement. I didn’t really know if we would get to the “arc” of the movement. I was really pleased that it came together as well as it did. We did a lot of really good structural work, taking those five main stories and building them into an act, then turning each act into an hourglass shape – start wide, focus on one story, then opening back out again to ramifications and consequences.

BN: Do you consider the film a success?

Kitchell: We made what we set out to make. And it’s amazing that we were able to pull it off and make it as good as we did. We wanted it to be one of the defining films of the environmental movement and we think it is. But it’s an entertaining film, too. It’s got good laugh lines, and material that will give you reasons to think.

BN: What next?

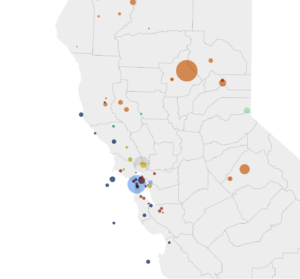

Kitchell: I am already discussing a follow-up movie, California Green Fire: Redwood battles, organic agriculture, air pollution, smog, climate. What is California’s unique role in addressing those issues? I hope that in a year or two we will see a rough cut. I recently got a $10,000 grant from Cal Humanities to work on this.

BN: What is your favorite outdoor destination in the Bay Area?

Kitchell: I love wandering around Point Reyes, but Mount Tamalpais is my favorite place without a doubt.

Learn more: To watch interviews, see the trailer, and download the film, visit www.afiercegreenfire.com