Matt Stoeker, director of Beyond Searsville Dam, is a homegrown activist. He grew up in Portola Valley upstream of the 65-foot-tall dam. He says that as a boy his chosen “religion” was to fish and explore Corte Madera Creek above the dam. The fish he saw in that creek were small, so when at age 19 he saw a 30-inch silver fish jump out of the scour pool at the dam’s foot, he was surprised. “Whoa, what was that?” he said to his friends. The fish, a steelhead trout, jumped out of the water several times in its attempt to get upstream. Each time it slammed into the dam.

“That moment of seeing that steelhead trying to swim home and bouncing off the concrete wall was something I couldn’t walk away from,” says Stoeker, who went on to study restoration ecology in college. Then he returned to his natal creek to start Beyond Searsville Dam, a nonprofit organization that wants to see the dam removed and wild steelhead back in their historic spawning grounds in Corte Madera Creek.

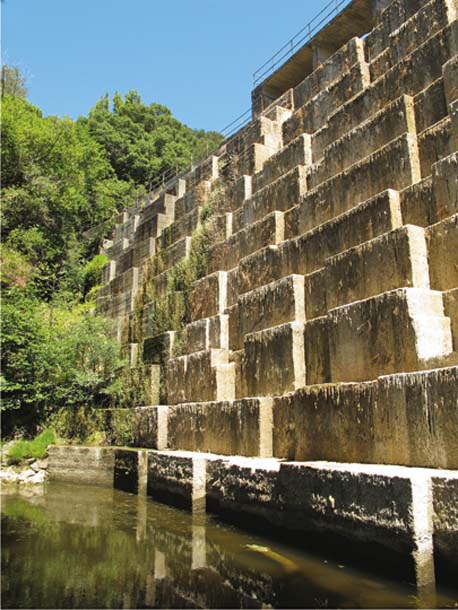

As dam sites go, Searsville is in an ideal location. Six creeks converge in a meadow upstream of a narrow gorge where the dam hovers above San Fransisquito Creek, one of few creeks flowing into San Francisco Bay that still supports a consistent steelhead run. Spring Valley Water Company built the concrete block dam in 1892 and in 1919 sold it to Stanford University.

A Stanford University steering committee is in the process of studying alternatives for future management of the dam, including its possible removal. Like most aging dams, this one is no longer efficient. Sediment accumulated in its reservoir has choked water storage capacity to ten percent of what it once was. But even with its hobbled capacity, the reservoir is a major source for the one million gallons of non-potable water used by the university each day, according to Stanford Report.

“It’s a complicated and nuanced issue,” says Philippe Cohen, executive director of the 1,189-acre Jasper Ridge Biological Preserve, about a fifth of which is occupied by the dam, reservoir, and associated freshwater wetlands. Cohen says the committee hopes to make a recommendation to the president and provost by the end of 2013.

Whether the dam comes down or stays, the biggest headache for the university is the sediment behind the dam. Should it be left where it is to protect the freshwater wetlands created by the dam, on which migrating birds have come to depend? Should it be mechanically removed (an expensive proposal), or should it be allowed to slowly flush into the Bay?

For Stoeker, that would be a win-win. Dams have been starving downstream wetlands of sediment for years, says Stoeker, who argues that the sediment will come in handy as sea level rises. “The only sustainable way to deal with rising sea levels is to have enough suspended sediment in the system,” he says. Find out more about Stoeker’s work at beyondsearsvilledam.org.