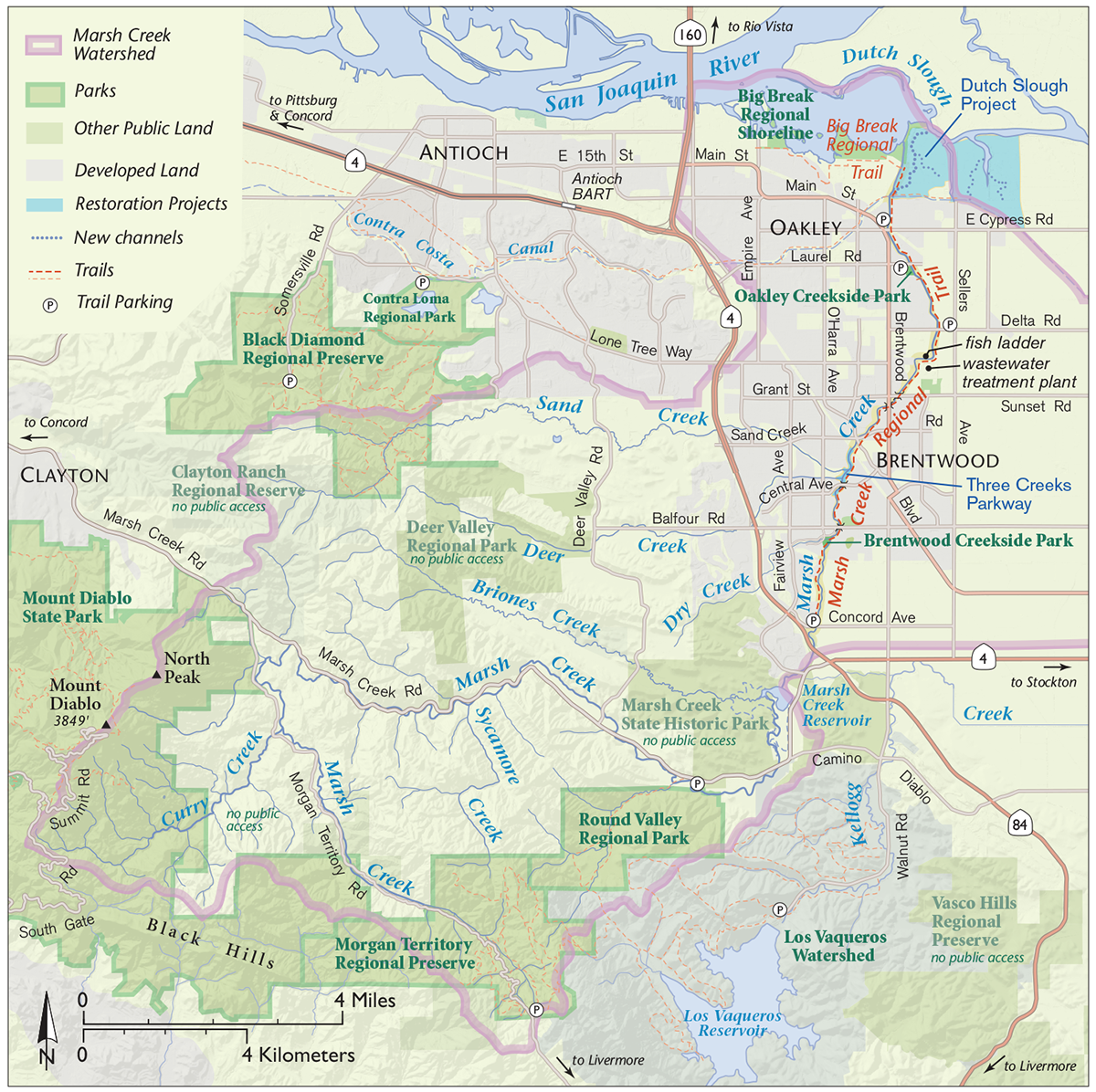

Marsh Creek begins high in the eastern foothills of Mount Diablo, where at 2,000 feet a series of springs is fed by groundwater and winter rains. In its upper reaches, this perennial creek plunges down steep, narrow canyons edged by a lush woodland of oaks, bay trees, and buckeyes, the water swelling as one tributary after another—Curry, Dunn, and Sycamore creeks—joins its nearly 20-mile course to the base of the hills. There the land flattens and, historically, the lower reaches of the creek then slowed and divided into two channels. Dry, Deer, and Sand creeks flowed into these waterways, which meandered across a vast grassy meadow dotted with majestic valley oaks, until finally flowing through freshwater tidal marsh thick with tules and reeds and into the Sacramento–San Joaquin Delta.

During heavy rains, Marsh Creek jumped its banks and spread over a huge swath of land where today the cities of Brentwood and Oakley sit. Indigenous peoples lived here for millennia, coexisting with the natural ebb and flow of the creek. But when European settlers converted the floodplain to agriculture fields and towns, the floods became devastating. A 1952 photograph shows people rowing past homes in the middle of what looks like a lake. Since then, lower Marsh Creek has been leveed, straightened, and stripped of vegetation; by the 1970s its transformation into a flood control channel was complete.

On a hot summer morning, East Bay Regional Park District naturalist Mike Moran and I stand on a bridge in Brentwood’s Creekside Park near the upstream end of the Marsh Creek Regional Trail, the eight-mile paved path that follows the creek from Brentwood to the Delta. Pick any point on the trail and you’ll likely see walkers, cyclists, or families with small children in strollers—or all three.

Remember, they are an exotic species in the Western United States, and are rapidly increasing their geographic range and range of habitats. Are they outcompeting or excluding native species in the process? How would we know? We have done almost nothing to monitor changes in the assemblage of mushroom species in areas before and and after the incursion of death caps.

Further Reading

Pringle et al, “The ectomycorrhizal fungus Amanita phalloides was introduced and is expanding its range on the west coast of North America,” Molecular Biology 2009

Lockhart et al, “Simultaneous emergence of multidrug-resistant Candida auris on 3 continents confirmed by whole-genome sequencing and epidemiological analyses,” Clinical Infectious Diseases 2017

Battalani et al, “Aflatoxin B1 contamination in maize in Europe increases due to climate change,” Scientific Reports 2016

Explore Marsh Creek Trail

» The Marsh Creek Trail can be accessed on foot or bicycle at many points along its length.

» Brentwood Creekside Park has ample curbside parking and had a port-a-potty near the playground at time of publication.

» To reach the fish ladder, park along Delta Road in Oakley near the intersection with Chrismore Drive, taking care not to block access for residents and working farms. Then head about half a mile south on the Marsh Creek Trail.

»Oakley Creekside Park has a large parking lot, picnic tables under a generous shade structure, and bathrooms.

»Oakley also has a small parking lot (10 spots) on the north side of East Cypress Road between Picasso Drive and Main Street. From here, the trail continues about a mile to the north and then meets the three-mile Big Break Regional Trail, which extends westward along Big Break Regional Shoreline.

Near the bridge, most of the creek bed is dry. Yet below us beckons a shimmer of blue: groundwater wells up here and there along the creek, forming pools that sustain wildlife through the long dry summers. Above us are huge oaks, sycamores, and willows that line the banks. “They kept the old riparian trees,” Moran says, greeting an ancient live oak like an old friend. “This is what the creek used to be like.” Besides giving us a welcome respite from the heat of the day, the shade of the trees helps keep the water cool enough for heat-sensitive fish. “People have seen salmon jumping here,” he adds.

Most of lower Marsh Creek is far less hospitable to fish and other wildlife. That’s about to change around a mile and a half downstream from the park. There, in the midst of Brentwood, bulldozers and excavators are reshaping the land flanking nearly a mile of Marsh Creek that includes its confluences with Sand and Deer creeks, which also begin on the eastern slopes of Mount Diablo. Called the Three Creeks Parkway Restoration, the $9 million project will yield two acres of floodplain and a canopy of riparian trees set in nearly 4.5 acres of grassland and oak woodland. Construction began in May and is scheduled for completion at the end of the year, with landscaping to begin after that.

Friends of Marsh Creek Watershed co-founder Sarah Puckett has dreamed of this day for more than a decade. “Marsh Creek is operated as a flood control channel, and the new vision is to operate it as a creek too,” she says. Puckett also helps manage the implementation of the Three Creeks project as a consultant for American Rivers, which is partnering with Contra Costa County Flood Control and Water Conservation District and others on the restoration. “It serves so many purposes, it’s important to balance them all.” Even though the balance is currently tilted toward flood control, she’s always amazed how much wildlife she sees in the creek, from muskrats to green herons to Chinook salmon.

“When the rains are early, salmon come in droves,” Puckett says. “I’ve seen dozens at a time swimming up Marsh Creek in the fall—and that’s without the restoration.” Salmon play an outsize role in watershed health. When it rains, nutrients from the land wash down creeks and into the ocean. Then, when adult salmon journey from the sea to streams, they help replenish what was lost. “They’re great retrievers—they eat in the ocean and bring nutrients back to the watershed,” Moran says. Predators and scavengers feast on salmon, and the fish that are uneaten decay and return nutrients to the soil, fertilizing plants. “It’s extraordinarily hopeful that they come.”

Salmon reach the Brentwood stretches of Marsh Creek courtesy of a fish ladder, which FOMCW and partners installed in 2010 about two miles downstream of the Three Creeks restoration site. Before the ladder went in, there was no way the fish could have made it farther upstream because they faced a six-foot-tall flood control structure. While salmon are champion leapers, they can’t get up enough speed in small waterways like Marsh Creek to clear a barrier that high.

Right by the fish ladder, the naturally seasonal creek is barely a trickle on this summer day. But a short walk downstream brings us to the outfall of Brentwood’s wastewater treatment plant, which mimics a rocky waterfall as it discharges into the creek. From here on, the creek burbles with water even during the dry season and is dotted with turtles sunning themselves. In another mile or so the trail passes through Creekside Park in Oakley, which is not to be confused with the park of the same name at the trailhead in Brentwood.

Here we get a glimpse of the wonders to come at the Three Creeks restoration. This park is like an oasis along Marsh Creek. A gently sloping footpath feels like an invitation to a grassy floodplain on the banks of the gently rushing water, so down we go, escaping the hot sun as we duck into the cool shade of the cottonwoods and other riparian trees overhead. At the edge of the creek, we plunge into the springy branches of a willow thicket, long narrow leaves momentarily enclosing us in a world of green. When we pop out on the other side, Moran is as surprised—and delighted—as I am to see a stack of gnawed-off saplings extending from one side of the creek to the other. Beavers are regulars at Big Break Regional Shoreline, which is nearby on the Delta, and he’d heard of sightings at this park. “But I didn’t know there was a dam!” he says.

The dam has been on the radar of Heidi Perryman, founder of Worth A Dam, a Martinez-based nonprofit dedicated to coexisting with urban beavers. Finding the balance between Marsh Creek as a wildlife haven and as a flood control channel is not always easy, and officials with the Contra Costa County Flood Control District worried that the beaver dam would flood the houses right across the creek from the park.

In May, Perryman was sad to learn that the county had destroyed most of the dam and hired a trapper to shoot the beavers. “They’re considered a nuisance and according to California Department of Fish and Wildlife regulation can’t be relocated,” she says. Since then, Perryman has advised the county on beaver-friendly solutions like potentially putting a pipe through the dam to keep the water from rising too high behind it. “There’s a whole beaver highway on the waterways here,” she says. “I told the county they’ll just come back.” What Mike and I saw were the remnants of the dam built by the exterminated beavers.

Many other animals also travel along Marsh Creek. “It’s a great corridor for wildlife,” says Moran, echoing Perryman. “It’s a highway for everything from mountain lions to mice.” About half a mile downstream from Oakley’s Creekside Park, the trail offers a stunning view along that highway: looking back south, we see the Black Hills of the Diablo Range where Marsh Creek originates. Facing forward again, we see a nearly 1,200-acre restoration site on its way to becoming wetlands at the edge of the Delta. This is Dutch Slough, a former tidal marsh that was diked off for dairy farming a century ago. Marsh Creek runs in basically a straight line toward the Delta, with Dutch Slough to the east and Big Break Regional Shoreline to the west, before emptying into the San Joaquin River’s fresh water.

Dutch Slough is already full of life. In rapid succession, Moran points out the muddy tracks a river otter left on the trail, a brush rabbit hopping by, and a kestrel flying overhead. He’s also seen bald and golden eagles. “There’s magical birding out here,” he says.

The Dutch Slough restoration will make it even more magical. Construction began in 2018 with redistributing 2.5 million cubic yards of dirt to reshape the land, where the elevation ranged from six feet above to six feet below sea level. Next native plants went in, including 50,000 transplanted water-loving tules, as well as riparian forest along the levees and berms. The next phase of the nearly $50 million project, scheduled for the late summer of 2021, will entail breaching the levees around the slough to let the tides back in.

Marsh Creek will gain a new, more natural mouth that meanders through the restored tidal marsh, and wildlife will gain a range of habitats from wetlands to uplands, according to California Department of Water Resources senior environmental scientist Katherine Bandy, who manages the project. The Dutch Slough restoration will also complement the Three Creeks restoration in Brentwood. “You need access to all that for salmon,” she says, explaining that upstream reaches of the creek provide spawning grounds while downstream marshes provide shelter and food for baby fish.

Bandy also is gladdened to know that people on the trail here are happy when they learn about the restoration. “It’s surrounded by development—they’re super excited it’s not more houses,” she says. One such local is Melissa Mohammadi, today out walking her dog on the trail. Charmed by Oakley’s access to nature, her family moved from San Francisco to a neighborhood overlooking Dutch Slough last summer. They love watching the wetland return right in their own backyard.

“We feel so fortunate to be able to walk out here every day and see what’s growing and who’s flying and skittering and skulking around. We had wild turkeys on our front porch, and we walk down to the trail sometimes at night to listen to frogs or look for owls,” Mohammadi says. “We’re just completely blissed out.”