From the top of San Bruno Mountain, a mile south of San Francisco, the neighborhoods below look insignificant. David Schooley, an environmentalist who has spent most of his adult life fighting to protect the mountain from development, points toward rows of tiny houses built on land once piled with trash. We are standing in knee-high native grass. “There’s Berkeley,” Schooley said, looking toward the barely visible University of California clock tower across San Francisco Bay.

I am on a tour with Schooley, founder of San Bruno Mountain Watch, a grassroots organization that has been leading conservation efforts on the mountain for more than 30 years. Every fourth Saturday of the month, Schooley takes a group of curious explorers on a hike like this one, educating them about the numerous endangered plants and animals on the mountain.

The famed Harvard University biologist E.O. Wilson once labeled San Bruno Mountain a global biodiversity hot spot, an area in need of protection, but it has suffered many years of habitat abuse and loss. Schooley and other members of San Bruno Mountain Watch have been trying to widen its appeal as a way to enlist the public in preventing further decline.

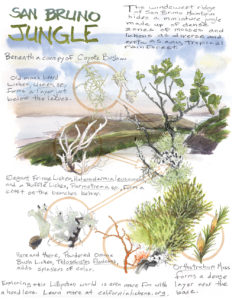

As people drive by on Highway 101, the mountain doesn’t seem like much more than a large grassy hill. “No one knows about the mountain,” says Joe Cannon, a consulting biologist to San Bruno Mountain Watch. “To many, we are just a grass field that people drive pass.”

Hidden from view, the mountain provides a safe haven for three endangered butterfly species and 13 rare plants. Its valleys and ridges, each with distinct ecosystems, support species limited to those areas. The undulating landscape gives hill-topping butterflies like the San Bruno elfin butterfly a chance to mate on high ground and lay eggs in lower areas. And yet its appeal to a developer is so obvious that when Schooley first saw it he asked himself, “Why is this still here?”

For 40 years in the mid-twentieth century, the mountain’s anonymity was its salvation. San Francisco used the area as a garbage dump, filling the marshes, lagoons and creeks. Nobody wanted to move into an area inhabited by such stench. “The garbage saved the land,” Schooley recalls. “People stayed away.”

In the 1960s developers sought to remove around 200 million cubic yards of dirt from the mountain to use as Bay fill. Public outcry, led in part by the newly formed Save the Bay, ultimately beat back the proposal. But it didn’t diminish the interest in the land, and the newly arrived Schooley, as part of a group calling itself the Committee to Save San Bruno Mountain, continued to fight off development. San Mateo County purchased 80 percent of the mountain in 1976, but Schooley became involved in another controversy, this time over the remaining 20 percent, which biologists had just identified as home to the endangered Mission Blue butterfly.

In 1983, the US Fish and Wildlife Service led an amendment to the Endangered Species Act that created the nation’s first habitat conservation plan, allowing development and the “incidental” destruction of endangered species and their habitat in certain parts of San Bruno Mountain in exchange for funding for restoration elsewhere. The plan was controversial at the time and has remained so ever since; Schooley says it “cleverly gutted the Endangered Species Act,” while others felt it was the best deal the rare butterflies and plants would get. The Committee to Save San Bruno Mountain dissolved in internal disagreement over the HCP. For more than 30 years, through development, preservation and restoration, those divisions have persisted. Schooley and San Bruno Mountain Watch continue to argue that the HCP has been bad for the mountain’s endangered species; that the point of the ESA is recovery and not just maintaining a small population in a fraction of a historic range, and that continuing to allow incidental take defeats any plans for recovery. But HCP supporters say it has helped preserve most of the butterflies’ habitat on the mountain while diverting more direct attacks on the Endangered Species Act, and that with adjustments it can continue to work.

The HCP expired in 2013, and was renewed for another 30 years. But the expiration and renewal also brought up a consideration of the past, and in 2014 the HCP trustees hired the Creekside Center for Earth Observation to prepare a 30-year assessment of the plan. That report is expected by the end of February.

One of the goals of the assessment is to better inform the preservation of the diverse habitats of the mountain. One thing everyone knows is missing, HCP Habitat Manager Ramona Arechiga said, is the mountain’s traditional ecological disturbers: fire and grazing, which over time gave rise to the mosaic of vegetation habitats found on the mountain.

While the big-picture plans take shape, though, the mountain remains to be discovered, visited, explored, and loved. Every Wednesday morning, San Bruno Mountain Watch nursery and stewardship coordinator Iris Clearwater leads a team of plant lovers in potting, watering and maintaining more than a hundred native plants inside a 2,000-square-foot greenhouse called the Mission Blue Nursery, located on Bayshore Boulevard behind the Brisbane firehouse. When the plants have developed healthy deep roots, volunteers transfer them to the mountain. Four times a year, members sell drought-tolerant native plants to the public to raise money for habitat restoration. Volunteers welcome people to less-traveled trails every first and third Saturday of each month, while Schooley leads tours every fourth Saturday. Little by little, they help make the mountain more accessible to a wider population, unveiling its mysterious façade.

Members also partner closely with the San Mateo County Park Department to maintain an abundance of trails that are suitable for families and individuals at every skill level.

Schooley hopes more concerned citizens will take part in the conservation effort. They can do so by joining mountain trails, volunteering at the nursery or planting, and preserving native San Bruno Mountain and the northern San Francisco Peninsula plants.

Starting in March, native flowers bloom and butterflies dance between valleys. On a recent hike, Schooley pointed out dormant plants and described the colors we’d see in a few months—fresh green and bright yellow. One day, San Bruno Mountain would not be “a place to get away from all, but a place to get into,” Schooley said.

-300x221.jpg)