There has been so much talk of a potential fracking boom in California. But how, exactly, did the Monterey shale formation become so valuable?

To help me understand why oil is trapped in this formation and why hydraulic fracturing and other methods of extreme energy extraction have been used to release it, UC Berkeley-trained geologist Mel Erskine meets me one day at the Tilden Botanical Gardens. He is carrying a geologic map of California showing the Monterey shale.

“It’s a formation that accumulated in deep structural basins during the mid-Miocene period,” says Erskine, an expert in the Monterey formation’s geography. “It’s very young. It’s six million years old or less.”

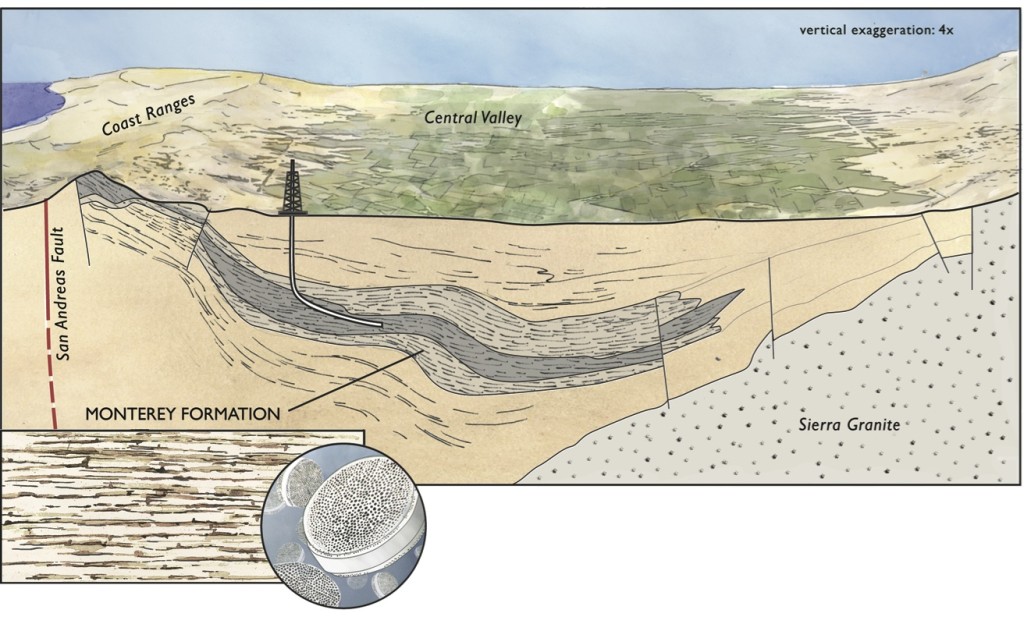

He unrolls the map, which is highly detailed and shows the Monterey Formation extending beneath central California to the coast and the Santa Barbara Channel.

Erskine explains that the Monterey formation is the source rock for a great deal of oil produced in California, which has been generated over millions of years by the conversion of tiny, dead marine organisms, known as diatoms, into hydrocarbons.

When these organisms died, they fell to the bottom of what was then an ocean and decomposed. The remaining biological sludge was covered by layers of sand and silt, and as the depth of the sediments reached 10,000 feet, pressure and heat transformed the organic compounds into crude oil. The formation doesn’t easily release the oil because the oil is sealed inside “a very tight shale.”

The purpose of fracking then is to break up the formation enough to insert a mix of chemical and coarse, well-sorted sandstone under high pressure into the new fractures. The sand sticks in cracks formed by the high pressure injection, creating fractures so that oil can flow to the wellhead. And the chemicals help to break up the shale and release the oil trapped within.

Fracking fluids often contain chemicals listed as hazardous pollutants, including benzene, lead and methanol. But because of legal trade secrets, oil companies typically do not disclose all the chemicals they use. The lack of transparency has outraged farmers, ranchers and environmentalists, who fear the contamination of water supplies.

Compared to more famous and heavily developed shales like North Dakota’s Bakken Formation or the Northeast’s Marcellus, the Monterey Formation is younger, with more internal folding.

“All the black lines you see on a geologic map of California are fault zones, so it’s very complex,” Erskine says.

You would think that all the tremors would make it easy to get the oil out.

But Erskine explains that the Monterey Formation is like a continually flowing subterranean creature: new fractures heal quickly as California’s active faults push and pull the rock. The process of fracking keeps the fractures open as long as is needed to extract the oil. To illustrate his point, Erskine takes me on a 5 minute drive to Grizzly Peak Road in the Berkeley Hills. He parks and grabs a small metal pick from his trunk. The roadside offers dramatic views of San Francisco Bay, but Erskine is drawn instead to a rock outcropping on the opposite side of the road.

“This is the Monterey shale,” he says, pointing at a yellowish-orange outcropping that looks like the ruins of an ancient miniature city and once lay thousands of feet below the surface of the Earth, until geological activity exposed it to the elements.

The shale is very brittle, Erskine says, pointing to rows of vertical fractures that mark the outcropping’s surface. This brittleness is one reason the formation can be fracked, he adds, breaking off a small chunk with his pick. A thin dark seam of oil glistens, then fades, like jelly oozing out of a peanut-butter-and-jelly sandwich.

“This is what we are trying to get to through hydraulic fracturing,” says Erskine, indicating the thin seam.

Could this ridge in the Berkeley Hills get fracked one day, if oil gets scarce enough? Erskine looks from the outcropping to the cliff edge, the steep drop, and the breathtaking views of the Bay, and shakes his head. The search, he says, is for areas where the formation is nearly horizontal.

“[The oil companies] can handle some dips,” Erskine says. “But basically they are going horizontally because they want to inject uniform pressure over a large area. In a steep dip like this there is no way to control the fractures.”

Erskine recalls how early on in his college career, he heard a geophysicist saying that the U.S. was close to peak oil production.

“That was 60 years ago, and the peak of oil and gas has been migrating through time,” he said. “What the development of the shales demonstrates is that you no longer need a reservoir of oil. You can make your own reservoir with these production methods.”

Erskine says his biggest concern about fracking is making sure that the process is well monitored.

“The operator has every incentive to keep the process completely under control,” he says. “Getting careless …. is a very expensive process.”

Preview of our next installment:

Are we fracking our way to the next Big One? And will methods of extreme energy extraction contaminate our water supply?

Read our first story in Bay Nature’s fracking series: In condor country comes a California oil boom.

Read our second story in the series: Above the Monterey Shale, farmers worry fracking will destroy the land.

Read our third story in the series: Fracking the land of the kit fox, and it’s fellow desert natives.

Sarah Phelan is a contributor to Bay Nature and is leading our coverage on Extreme Energy in the Monterey Shale.