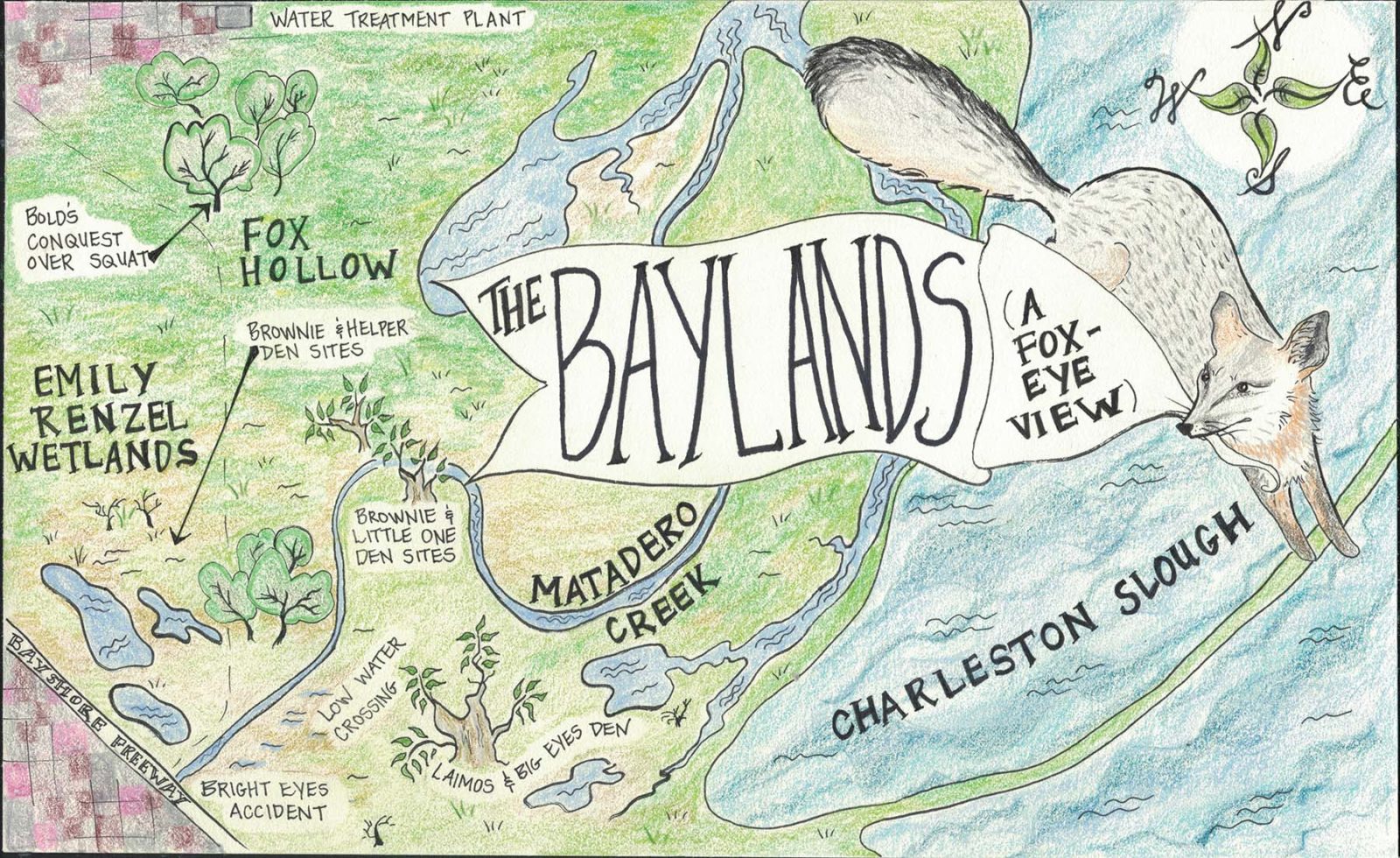

The Palo Alto Baylands are roughly three square miles in area, a little corner of relative wildness carved into the deep south end of San Francisco Bay where 15,000 years ago Columbian mammoths and dire wolves roamed a grassy river valley. Within the wetlands, a cement overflow channel fills with floodwater during heavy rains. A water treatment plant hums steadily and a drainage pipe, still wet with raccoon tracks from last night, sieves salt water into the wetlands. But between the channels and pipes, the Baylands are snarled with small trees and tall grasses gone blond with summer heat: perfect habitat for Urocyon cinereoargenteus townsendi, the Townsend’s gray fox.

Gray foxes are elusive but not rare—in the last year alone, citizen scientists logged nearly 350 sightings of foxes on the iNaturalist biodiversity map of the greater Bay Area. Families of foxes have resided on the Facebook headquarters campus since it opened in 2011, gaining a broad online following of enthusiasts. In 2015, a solitary gray fox became a local news celebrity at San Francisco’s Presidio—the first sighting within the park in over a decade. (Around the early 2000s coyotes, which are not above making a snack out of a fox, began making a comeback in the city.) But the Palo Alto Baylands, one of the largest fragments of intact marshland remaining in San Francisco Bay, are the nucleus for what we know about the local lives of these shy animals—in the same way that Tanzania’s Gombe Stream National Park became the geographic heart for the world’s understanding of wild chimpanzees. And just as Gombe had Jane Goodall’s sharp-eyed attention, the Baylands have their own documentarian, too.

Bill Leikam, “the fox guy,” unlatches the casing for one of his wildlife cameras in the predawn gloom just past the end of Palo Alto’s Embarcadero Road. The smell of the marsh settles around us: bitter willow, pungent eucalyptus. The coffee hasn’t yet hit my bloodstream, but Leikam deftly slides out the memory card and inserts a new one with the spry fingers of someone accustomed to rising early. For 12 years, Leikam—a high school English teacher turned trailblazing citizen scientist—has watched the Baylands gray foxes. The foxes, indisputably, have watched him back.

Leikam’s pointing finger throws a heavy shadow across his headlamp beam as he gestures toward the brush at the edge of the path, showing me where, generations ago, he first met Squat, an inquisitive fox that allowed Leikam to linger and watch him go about his daily deeds. Leikam assigns names to the animals he watches: a warmer kind of science than numbers. “Squat,” Leikam tells me, “taught me the basics of being a fox.”

The observations that Leikam makes—dutifully, every day at dawn and dusk—are examples of ethology, the study of animal character. The earliest ethologists—Nikolaas Tinbergen, Konrad Lorenz, Karl von Frisch—were interested in individual variance. Like butterfly collectors, they wanted to catalog the dazzling diversity of animal behavior not as measured in a lab, but as witnessed in the full and complex context of the natural world. When they were jointly awarded the 1973 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, it was for their work in decoding the information that animals pass to each other. Ethology, even now, says Robert Sapolsky, neurobiologist at Stanford University, is the process of “interviewing an animal in its own language.”

Every month, Leikam types up his field notes, and they have become a chronicle of family dramas and tender gestures and nightly hunts. Leikam knows where the foxes nap in the crooks of trees, anticipates their shift from syrupy summer fruits to the rich meat of their winter diet, watches their tails sweep from side to side when they are happy, sees where they bury their food and cleanly mark the edges of their territory, listens to them call out to one another in hoarse and raspy voices. The Baylands landscape is pressed deeply with the prints of generations, and Leikam’s reports are enough to fill a textbook. But, much as naming the animals shifts the relationship between scientist and subject, Leikam’s intimate and long-spanning observations shift the focus of natural history from that of understanding species to that of understanding individuals, with interwoven communities and kaleidoscopic nuance. When specific populations are watched with a patient gaze, “generalities come apart,” Leikam says.

It was in 2014, when December was drawing new grass up through the Baylands mud, that Leikam first came to understand how different foxes are from one another. Rain had flooded a low-lying area beneath a tangle of willow branches, and Leikam had sloshed through it on his way to his next field camera. But three foxes—all following him, as the foxes in the Baylands often did for Leikam’s daily rounds—hesitated. Gray foxes do not like water. Leikam watched each fox approach the dilemma independently. A teenage pup splashed through water to catch up with Leikam, but Dark Eyes—the alpha female of the whole region—stuck to the edge of the puddle, avoiding the wettest places. Meanwhile, Cute leaped sideways to a low bough and threaded her way across the flooded area along tree branches, keeping her paws dry. Leikam used to think that foxes were “running on instinct,” he confides as we scuff across the now-dry puddle, but “they’re as individual as you or me.” They can make choices about how they want to behave, and they can also make choices about the future—Leikam has watched the foxes that often accompany him at a curious distance on his morning rounds take shortcuts in order to meet him at his next wildlife camera site: evidence that they can remember, foresee, strategize, and plan.

The gray foxes of the Baylands, with their bright minds and curious behavior, have shown Leikam “how to be a fox,” but the rulebook is full of exceptions. Out in the marsh, near the tall eucalyptus west of Charleston Slough, Little One and Brownie raised two litters together. Their family was the first documented fox family in the area with a “helper”—a lone female, often a grown pup without her own territory, who sticks around to assist in raising another pair’s pups. Since that time, other helpers have been observed, and successful litters have been raised with their assistance. Little One couldn’t have anticipated that Brownie would disappear one day with Helper and never return. He set up a den with his new mate out among the sweet fennel and wild oats in the Emily Renzel Wetlands. For a long time afterward, Little One would go wandering in that direction, maybe looking for her lost mate, until eventually—perhaps understanding what had come to pass—she crept away. Gray foxes are socially monogamous for life, meaning they stick with their partners and work together until death parts them. Studies have shown that occasionally gray foxes—male and female both—will stray from their territory to mate with other foxes during the breeding season, but they return and care for their young together, often exhibiting extraordinary tenderness. Brownie’s divorce from Little One was something different, and in Leikam’s experience, unprecedented.

The spectrum of fox behavior is not unlike the landscape these animals inhabit in the Baylands—well-traveled trails, with a tangly wilderness of possibilities on either side. Alongside the occasional infidelity, there’s a capacity for deep family bonds. In 2013, among the dry willows on the Matadero Creek floodplain, two siblings learned together how to be foxes, strong and limber. Bright Eyes would leap at her brother Dark Face, who would spin and run toward her. They would skate to a halt, facing each other with bobbing heads, then leap again into the chase. Together, they wrestled beneath the trees and wove through the dead branches like dancers.

When Leikam found a bundle of fur by the side of the road in the early hours of September 1, 2013—a female gray fox knocked lifeless by a car in the night—it took him three days to acknowledge that it was the body of Bright Eyes. During that time, neither of Bright Eyes’ parents emerged from the bushes as usual to greet Leikam on his morning rounds. Her brother would return often to the floodplain near the trees where he and Bright Eyes used to play, looking out across the wide marsh. He limped on his left leg, perhaps clipped by the same deadly car as the siblings bounded together too close to moving traffic. Dark Face moved slowly, heavily, as if weighed down. “They were family,” Leikam wrote of the separated siblings, “in the deep meaning of that word.”

Both gentleness and violence punctuate the lives of gray foxes. A “fox kiss” is a universal gesture: a damp and delicate touch, nose tip to nose tip. Conversely, combat between foxes is ferocious. A fox fight is swift—in the time it takes to draw a deep breath, whole wars are begun and finished. Squat, the presiding Baylands alpha male, first presented his daughter to Leikam when she was still a pup. Squat emerged from the bushes and sat at the edge of the path, glancing behind himself until, a few minutes later, a pudgy little fox materialized. She touched snouts with her father and looked across the path at Leikam—an introduction, of sorts. Bold soon earned her name, appearing alone to daringly watch Leikam while her siblings stayed hidden in the brush.

But when the time came in 2011for Bold to claim land for a den of her own, rather than dispersing, as is typical, she approached Squat and challenged him for his territory. All teeth and claws, Bold fought and defeated her father in mere seconds, taking possession of the same land where Squat had raised her. In the unruly moment that the fight lasted, Leikam captured a photograph of the violence: Bold airborne, mouth open, her teeth as luminous as a new set of knives. It was the stuff of Greek theater—the ticking of the generational clock, a father’s conquest, the rise of a new empire. It is also the stuff of ethological breakthroughs—behavior like Bold’s is “phenomenally important in understanding social dynamics,” says behavioral ecologist Marc Bekoff, professor emeritus at CU Boulder, who leans forward excitedly as he listens to me relay the story after I return from my adventure with Leikam. “An observation like that could generate 20 theses in a heartbeat.”

After overthrowing her father and claiming her natal territory, Bold became Mama Bold, and together she and her mate Gray reared families of their own—five pups nearly every year, raised on warm milk and the dark meat of woodrats in the brushy neighborhood of Fox Hollow. The pups’ sharp teeth drew blood, so Mama Bold would often lie a few yards from the den. Gray would wander the marsh, returning with food, and he tended to parenting tasks in the den. When the pups were hungry, Gray would approach Mama Bold with a soft nudge, and she would return to feed them. Together, they taught their young how to climb trees, how to hunt. In quiet moments between duties, when Gray lounged in the clearing, Mama Bold would snuggle against him and lay her chin across his warm belly. Curled against each other like this, they would nap.

Betrayal, altruism, loyalty, grief. These are recognizable behaviors that reveal not only sharp intelligence, but a nuanced capacity for emotion that eclipses raw instinct. If gray foxes can abandon mates, mourn lost companions, care for young that are not their own, and live long lives in unbroken devotion to one another, perhaps the rulebook needs to be rewritten with attention paid not just to natural history—hierarchies, life spans, diets—but with a deeper consideration for the life of the mind. Leikam has come to understand that these animals lead complex “emotional and intellectual lives.” He once watched a fox pup as it slept. “All of a sudden, his hind leg went pop, and it was moving, and that’s a signal that they’re dreaming … I said, ‘What’s going on in that little fox’s mind?’”

It’s a mystery Leikam is still working to unravel. He suspects that foxes might experience their world synesthetically: that is, that they blend their senses and might be able to “smell sound” or “hear odor.” With such keen tools of perception, a fox’s mind might work in ways that science has yet to measure. Leikam has watched, for example, solitary foxes facing a frightening or challenging experience. Other foxes seem to know what’s happening, and will arrive “in times of need from long distances.” What does a fox dream of? What can these animals hear or feel that we cannot?

These questions get at the heart of ethology, a field that has roots not just in muddy-booted natural history but in the study of the mind. Mid-century scientists called behaviorists were frustrated by the “soft science” of psychology, which at the time was a much more introspective, philosophical field than it is today. The behaviorists were keen to make psychology quantitative, to slim behaviors down into universal rules that could be applied across all species. Ethology arose in resistance to this. Where behaviorists sought clean uniformity, ethologists paid attention to variation. Where behaviorists tried to pinpoint rules, ethologists made theirs the study of exceptions. Their questions—then and now—consider individual motivations and individual minds. “What it’s all about,” says Stanford’s Sapolsky, “is recognizing that other species out there are functioning in sensory modalities we can’t even guess at.”

Leikam didn’t think much of it when, in 2016, he started noticing goopy discharge in several foxes’ eyes. He made note of it, but he had witnessed the staggering strength of foxes’ immune systems—their ability to heal swiftly from injured paws and the raw wounds from fights. Yet by the end of the year, 25 Baylands foxes turned up dead—wiped out by a highly contagious viral infection called canine distemper.

Gray. Brownie. Little One. Dark Eyes. Mama Bold. Foxes disappeared entirely from the area—whole families, lost lineages. In their absence, Leikam watched the marsh change. Woodrats, jackrabbits, and field mice exploded in number. The meadows and trails busied with lizards, gopher snakes, gophers, voles, and squirrels—all of which Leikam watched transform the vegetation of the Baylands. He describes gray foxes as keystone predators: animals that, by virtue of their diet, keep whole ecosystems in check. Observations like Leikam’s lay the groundwork for understanding those systemic balances. “You need these data in order to do behavioral ecology,” Bekoff says. The fieldwork, he says, is “foundational.”

For two years and one month, Leikam kept up his daily walks, hoping for a reappearance. Occasionally, video would show up on one of the feeds: a vagabond fox moving through in the night, dark and smooth. But it wasn’t until February of 2019 that foxes finally returned to stay. Now Laimos—Greek for “long neck”—and his mate Big Eyes have taken up residence at Matadero Creek. They have yet to have any pups.

This morning, Laimos approaches us in the dry overflow canal and sits nearby, watching us with glittering eyes. He yawns. Does the future of fox-kind in the Baylands weigh on his gray shoulders? Leikam would argue that more foxes will come, but only if corridors between fragmented marshy refugia can be planted with fox-friendly brush, and only if tracking collars can be used to help us better understand fox dispersal in the few remaining wildlands of the South Bay, both the work of Leikam’s nonprofit Urban Wildlife Research Project.

Gray foxes evolved between 8 and 12 million years ago, when the Grand Tetons first began forming and when disorderly Sierra Nevada canyons still filled with down-rushing volcanic lava flows. Gray foxes have been on this planet longer than all other canids; in evolutionary circles, they are called “the basal canid”—the original dog. Since their ancestry is rooted in a time before other canines, they cannot interbreed with other species in the manner of coyotes and wolves or wolves and domesticated dogs. To look at a gray fox is to look at an unbroken genetic lineage that goes back perhaps as far as 12 million years. A gray fox is an ancient thing.

During the last great ice age, the climate swings of the Pleistocene divided eastern and western gray fox populations. California became a refugium where species took shelter from an increasingly arid continent and from an ice sheet that pressed across middle America like a two-mile-high earthmover.

Considering the landscape of the Bay Area today—partitioned by highways, stitched together by bridges, patchworked with neighborhoods and tech empires—perhaps green spaces like the Palo Alto Baylands serve as another sort of refugia. Hemmed in on all sides by a landscape that looks very different than it did at the end of the Pleistocene, do gray foxes here continue to adapt to their environment? Occasionally, Leikam receives notes from biologists elsewhere, suggesting that seasonal diets or behaviors of the foxes they study are different from the findings in Leikam’s reports. The lives of Bay Area gray foxes, it would seem, are unique to Bay Area gray foxes.

Slow, observant science like Leikam’s is rare and important. Where other disciplines might seek averages, ethology recognizes specific stories. It is a tool for understanding localized natural history, intimately. Linger long enough, and the shy gray fox might reveal something to the patient observer that it has never shared before. Interview them in their own language, and these primeval first dogs might still have lessons for us: how to be a fox; perhaps how to better be human.