It’s quite odd, when you stop and think about it, that landscapes shaped by millions of years of wind and rain and tectonic shifts, by countless millennia of vegetation growing and animals digging and dying, such that their boundaries follow the contours of nature, now find themselves shaped by people: not just by ribbons of pavement and power lines, but by lines on maps. Lines at once ephemeral and arbitrary and incontrovertible.

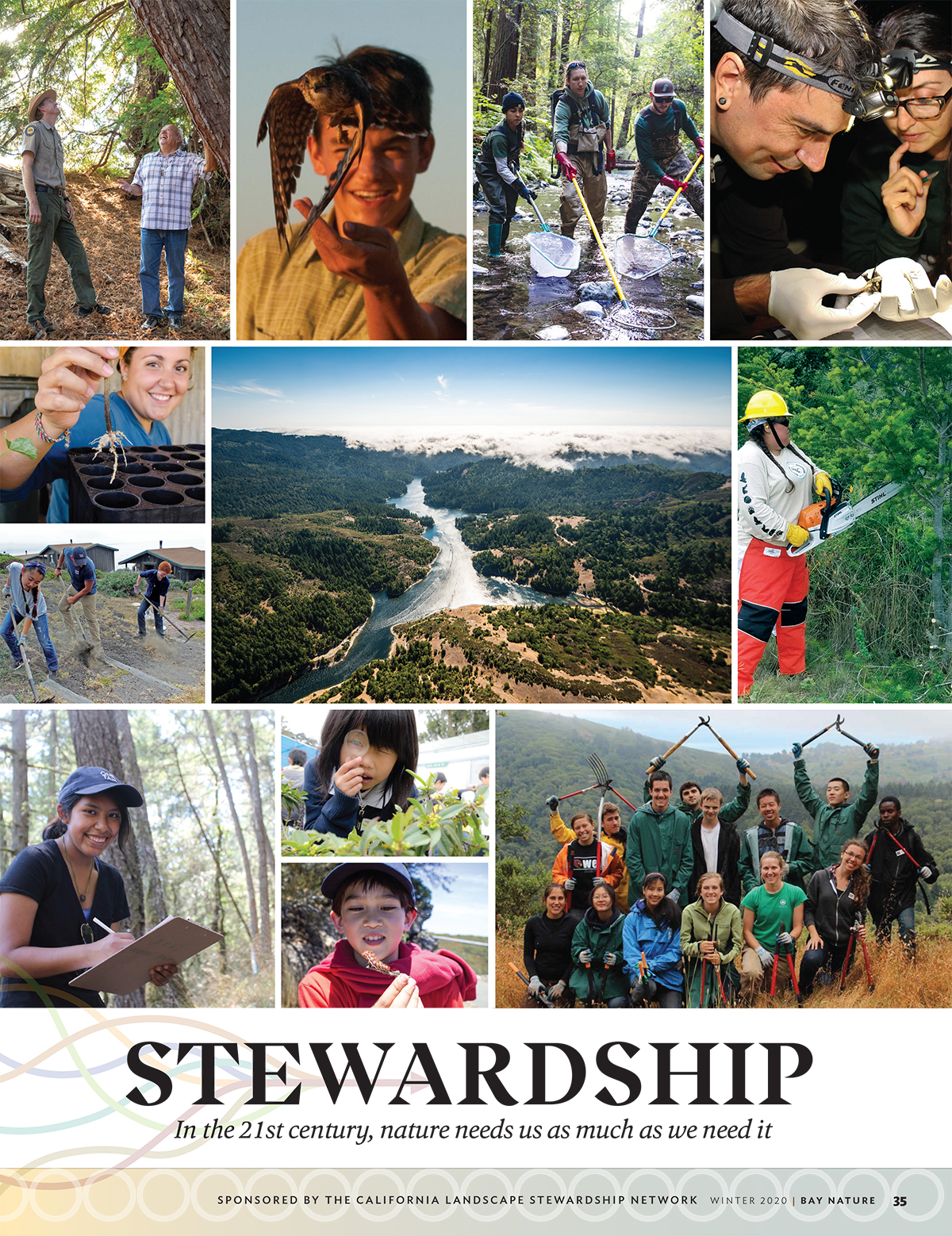

21st Century Stewardship

This series of stories sponsored by the California Landscape Stewardship Network explores the ways modern conservationists seek to define a new relationship with the natural world. Read more:

»What Stewardship Looks Like in the Santa Cruz Mountains

»One Tam’s Meteoric Rise in Marin

»One Tam: Bees Bring a Mountain Together

»One Tam: Where the Wildlife Are

Consider Redwood Creek, bubbling down the slopes of Mount Tamalpais in Marin County through no fewer than three jurisdictions—a state park, a national park, and a municipal water district—and a gauntlet of stakeholders, from neighborhood associations to property developers to conservation groups. The watershed doesn’t care who owns the land. Neither do the animals nor the plants. Yet this patchwork of claims and interests will determine their fate, and navigating it is a central challenge of conservation in a human-dominated world.

“It means working across boundaries,” says Sharon Farrell, who oversees projects, stewardship and science programs at the Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy. “Looking at the landscape in terms of what the landscape means and not the boundaries that have been set.” And that, in a word, means collaboration.

This is a bit of a buzzword in conservation circles, although it should be understood that the idea of people with different interests working together on such matters, and encompassing not just formally protected areas but also those places where people live and work, is not exactly new.

California’s state park system, born of public consultation and now reliant on volunteer help, is a testament to cooperation. Federal forests and rangelands are, in the argot, multiuse. Hunting regulations and environmentally oriented zoning requirements reflect an intertwining of nature’s stewardship with society’s everyday functions.

The shape and scope of such collaboration have continued to evolve, though, and at this early 21st-century moment are more important than ever. As government agencies confront dwindling budgets and growing resentment of top-down directives, the need to speak with rather than at is unavoidable. The high cost of land makes it hard to establish new large-scale parks and refuges, thus pushing more attention toward stewardship and management.

Most important, there’s a growing awareness that preventing extinctions and extirpations and a collapse of biodiversity requires working across geographically vast areas. Linking far-flung redoubts of nature so they don’t become isolated islands in a sea of sprawl, protecting seasonal animal migrations, helping species survive a fast-changing climate: these cannot be accomplished in piecemeal or localized fashion.

All this has encouraged a rise of conservation alliances, or collaboratives, that gather many stakeholders under a single figurative tent—some locally oriented, like One Tam, with its emphasis on the Mount Tamalpais watershed, and others encompassing large regions, like the Santa Cruz Mountains Stewardship Network.

The national Network for Landscape Conservation, which aims to share best practices and lessons learned, launched in 2011 as such collaborative efforts seemed to blossom. In a subsequent survey, the organization cataloged 130 such landscape-scale conservation efforts in the United States, nearly half founded in the last decade; Farrell put the figure around 500.

“When I started in this field, we talked about watersheds, about ecosystems. Now there’s a recognition of the scale and size of the landscapes that we need to work with.”

Whatever the precise number, the implication is clear. “When I started in this field, we talked about watersheds, about ecosystems,” she says. “Now there’s a recognition of the scale and size of the landscapes that we need to work with.”

The emphasis on collaboration actually dates to the inception of American conservation: Gifford Pinchot, the first head of the U.S. Forest Service, was just as influential—some would argue more so—as John Muir, balancing protection of natural communities with the economic interests of human communities. Aldo Leopold, best known for preaching responsible membership in a larger ecological community, was also tireless in fostering relations between farmers, academics, and government officials in southeastern Wisconsin.

Yet after the pitched environmental battles of the 1960s and 1970s, as frustration mounted with the adversarial gridlock of lobbying campaigns and courtroom disputes, the early 1990s witnessed the birth of collaborative conservation as a formal movement. It “reaches across the great divide connecting preservation advocates and developers, commodity producers and conservation biologists, local residents, and national interest groups,” wrote Philip Brick, Sarah Bates, and Donald Snow in Across the Great Divide: Explorations in Collaborative Conservation and the American West, published in 2000. “This new movement represents the new face of American conservation as we enter the 21st century.”

Among the collaboratives they discussed were the Quincy Library Group in northeastern California and the Malpai Borderlands Group at the southern confluence of Arizona and New Mexico. They traced the movement’s origins to the western U.S., where the presence of large-scale public lands necessitated negotiation between different groups. (There are plenty of examples from the eastern U.S., too, such as Wildlands and Woodlands in New England, or Adirondack Park in upstate New York.)

The rising popularity of land trusts and conservation easements, which often protect habitat from development while allowing existing uses to continue, also fed into the collaborative spirit. There are an estimated 500 local-scale collaborations in Colorado alone, and large-scale projects—like the Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative and the California Landscape Stewardship Network’s state-spanning union—are growing fast.

Ambitious visions like that popularized by E.O. Wilson’s Half-Earth Project and the Nature Needs Half network, which call for protecting half the planet and managing the other half responsibly, “absolutely have to be done at the collaborative scale,” says Jonathan Jarvis, former head of the National Park Service.

Yet with scale come complications: different agencies and organizations may have different policies. Seemingly small details—volunteer training standards, sharing equipment, filing paperwork—can turn into challenges.

Overcoming these all-too-human obstacles and keeping people engaged is much easier when there’s a strong, dynamic leader heading an effort, someone with vision and a deft touch. Finding that person can be a challenge, too. “A lot of these groups depend on someone with real leadership skills to bring people together, to instill confidence,” says Brick in an interview. “There’s not enough leadership capacity.”

And while collaborative approaches are rightly framed as preferable to public disputes and legal wrangling, the threat of such adversarial relations can likewise incentivize negotiation. If the current regulatory rollback continues, environmentalists may lose the power to stop nature-destroying projects, adds Brick. Then powerful interests don’t need to sit down and talk. “We tend to think of collaborations as people getting together and solving problems,” he says. “There is that, but they get together because the adversarial system doesn’t work for anyone.”

As collaborations grow in scale—not just a forest or a creek, but a wildlife corridor spanning multiple states or even much of a continent—another potential complication emerges: large, well-funded groups may edge out smaller, local actors. Yet those smaller actors have a passion born of connections to a particular place and the local knowledge essential to getting things done. “We’re talking to people about places they know and love,” says Lisa Brush, executive director of The Stewardship Network in Ann Arbor, Michigan. “As you scale much bigger, it becomes much less tangible.” Abstracted interests become prioritized—such as environment versus development—rather than the need to find working solutions that involve compromises.

In short, collaboration isn’t always easy. Neither is it a panacea. But making conservation work at the scales necessary to keep nature rich and abundant demands it. And in a world where the fate of nonhuman communities will be determined as much by human relationships and cooperation as by natural conditions, it’s essential.