At the north end of Lake Almanor the waters recede into a marsh of rushes and sharp-edged sedges. In early summer, when Lassen Peak still shimmers in snow on the horizon, sandhill cranes are slurping up seeds and snails near nesting sites at the edge of the bog. As the land rises the waters dry, giving way to mats of grass scattered with willow clumps. Yellow warblers are chirping in wispy song as they flit among the catkins, sharing the space with willow flycatchers. Today Chester Meadow—one of the largest meadows in the Sierra Nevada—basks in the promise of permanent protection. After a century under Pacific Gas and Electric Company ownership it is now safeguarded from development … forever.

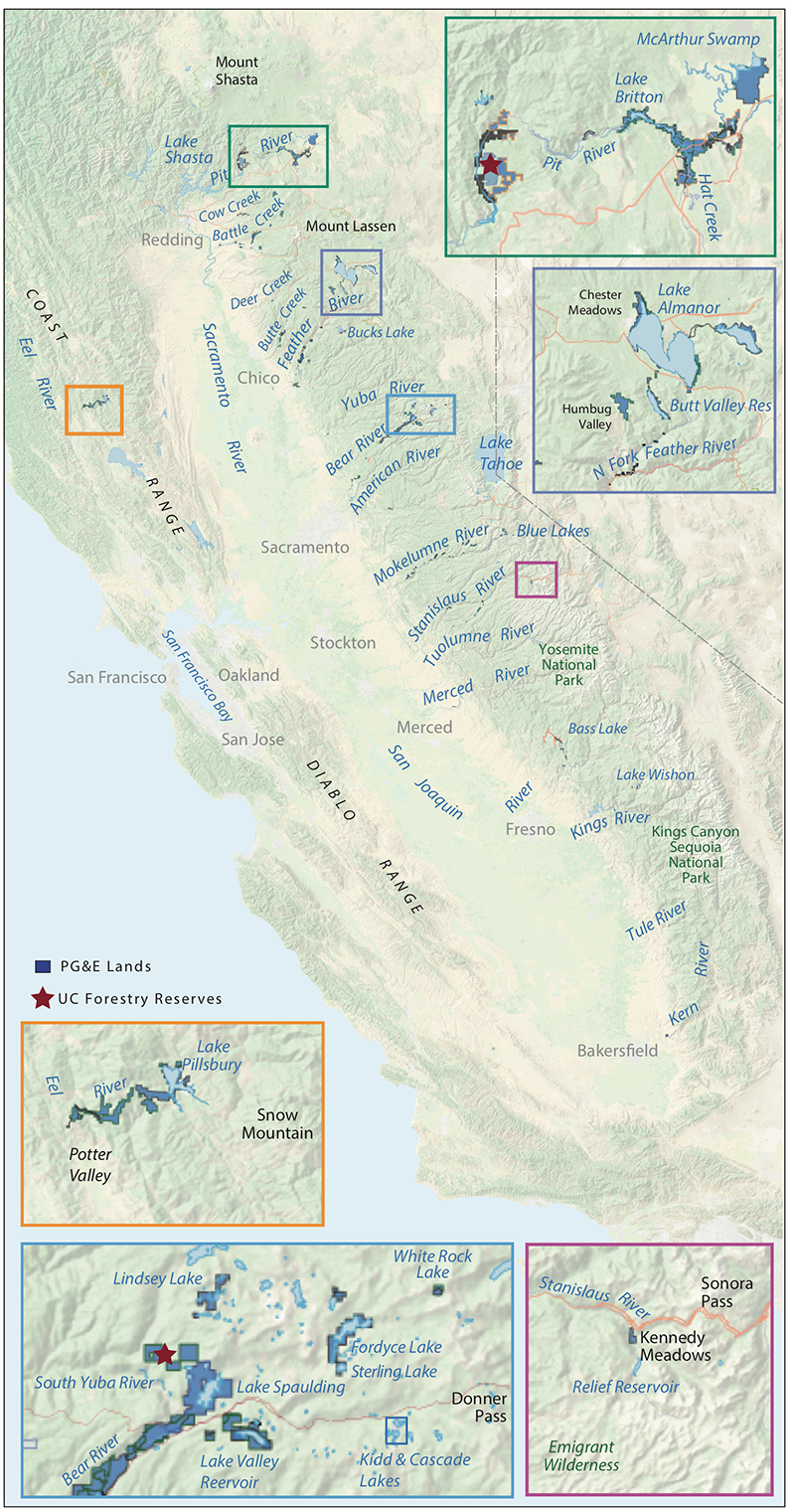

These wetlands in the Feather River headwaters are part of a bonanza to the citizens of California—an expanse of land more than four times the size of San Francisco conserved for its open space and wildlife habitat. Credit PG&E’s bankruptcy—the previous one. In a 2003 settlement hailed as a landmark conservation deal, California officials and ratepayers agreed to bail out the giant utility in exchange for 140,000 acres of forests and wetlands, protected for conservation in perpetuity. The lands, which include some of California’s most prized and sensitive landscapes, stretch from secluded meadows near the Oregon border to the veldt-like Carrizo Plain near Bakersfield. Among them are verdant valleys in critical headwaters and McArthur Swamp, an important stopover for birds migrating from California’s Central Valley to the Klamath Basin and beyond.

The deal, negotiated by a coalition of environmental, hydropower industry, and state and federal agency groups, designated some of these lands for transfer to new owners who would commit to enhancing their natural resources and keeping them open to the public. Lands critical to PG&E’s hydroelectric operations would remain under the company’s ownership but safeguarded by a conservation easement to protect their cultural value and open space.

State and environmental leaders were giddy with excitement over this stunning windfall. “You’d have to look at the creation of the national parks here to find anything comparable,” said John McCaull, the California legislative director for the National Audubon Society at the time the issue was under debate. It’s a gift to California that allows the state to keep these lands for public use, “not just for our generation but for generations to come,” said Michael Peevey, then president of the California Public Utilities Commission.

Historic and momentous as it was, the agreement promised more than it has delivered. Conservation groups fully expected new owners to take possession of at least half of the 140,000 acres, preserving and improving them after decades of neglect. Sixteen years into implementation of the deal, the reality is harshly different. With most of the land transactions at or near completion, PG&E will remain the owner of more than 70 percent of the original donation.

“It is a vision unfulfilled,” says Laurie Wayburn, co-CEO and president of Pacific Forest Trust, a conservation organization.

The vision for protecting these critical ecosystems was born out of the panic of losing them. In the early 2000s PG&E was considering auctioning off its hydroelectric assets to raise desperately needed cash. It had amassed properties worth over $1 billion during a century of developing its hydroelectricity empire. Wherever it built a reservoir to store the water that turns the turbines, the company acquired adjacent land. In 2001, when PG&E was scrambling for money, these non-essential lands were attracting interest from loggers and developers covetous of the revenues they could reap from forests and housing sites on parcels long off-limits under PG&E ownership.

Wayburn was among those working to thwart landscape-scale alterations to the California environment. As president of the Pacific Forest Trust, which advocates conserving productive private forests, she had been in discussions with PG&E officials about protecting their lands with conservation easements as they looked for ways to monetize their assets. The company’s April 2001 bankruptcy filing offered an opportunity. The public had a long history of engaging with PG&E lands, camping in its forests, swimming and fishing in its reservoirs. Citing a public trust benefit, Wayburn reasoned that if the utility was going to divest itself of those lands, why not insist that they divest by either transferring the title to a conservation owner or subjecting PG&E to a conservation easement?

“These lands should be conserved,” Wayburn contended in 2001. “They shouldn’t just be marketed off.” She made that argument to Barbara Hale, the administrative law judge overseeing the bankruptcy process. Hale agreed.

When the company emerged from bankruptcy in April 2004, the settlement agreement established the Pacific Forest and Watershed Lands Stewardship Council, a nonprofit foundation tasked with recommending future owners for parcels in 21 counties from Shasta in the north to San Luis Obispo in the south. Composed of representatives of entities ranging from state and federal agencies to water districts and forest and conservation organizations, the council set to work proposing safeguards for each of the nearly 1,000 parcels, watershed by watershed.

Council members knew from the start that lands essential to generating hydroelectricity would remain in PG&E ownership. That left 88,000 acres outside the boundaries of hydro projects regulated by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), according to estimates developed for PG&E’s proposed auction. Conservationists had visions of transferring these lands to new owners who would manage them for climate resilience—returning natural fire to forests and restoring wet meadows to hold water into the dry summer months. Although PG&E has kept its hydro-related lands largely free of development, its primary responsibilities are to its stockholders and state regulators, not natural resources, says Pacific Forest Trust board member Andrea Tuttle, who was director of California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection at the time of the bankruptcy. New owners could offer new opportunities, she adds: “There was an expectation that…this would be a boon to California’s public land base.”

The lands remaining with PG&E would be protected by conservation easements limiting their use. Each easement would be designed to fit the natural assets of the property, but all would prohibit activities damaging to natural resources. No housing or other development would be allowed. The bankruptcy agreement provided $70 million from PG&E to support the land conservation program. New owners would receive transaction and land stewardship funding, potentially including payments to counties to offset property taxes. The program also provides as much as 100 percent of the costs land trusts incur for monitoring conservation easements.

Other terms of the agreement were more controversial. They allowed PG&E to repay the $13 billion it owed its creditors but left around $2 billion of that to be footed by its 4.8 million ratepayers—as much as $1,700 per customer. Ratepayers also covered the $70 million supporting the conservation program. Critics called the deal too lucrative for PG&E, too costly for ratepayers. In the year before the April 2004 settlement approval, the company distributed $84 million in bonuses to 17 current and former executives and awarded then-chairman Robert D. Glynn Jr. $17 million.

As the Stewardship Council began the task of allocating ownerships, it faced an initial disappointment. The settlement agreement designated just 44,000 acres available for new owners—half the acreage estimated during the pre-bankruptcy period. It identified 96,000 acres essential to the company’s hydroelectric operations. “In a perfect world, we would like to see more of that land in new ownership,” says Dave Sutton, a member of the Stewardship Council representing Trust for Public Land.

Chester Meadow might have been a candidate for private ownership. Part of a 1,850-acre parcel that climbs beyond the reservoir to include forestlands, it is at the farthest reach from the dam that created Lake Almanor and the equipment that regulates water flowing into PG&E’s hydroelectric turbines. The meadow is the second-largest breeding ground in California for little willow flycatchers, a state listed endangered subspecies. Yellow warblers breed here in the highest density ever documented in California, and one of the largest migratory deer herds in the state comes here to birth its fawns.

But PG&E claimed this area as essential to its Feather River hydropower system and will retain ownership. That limits the protections for this “crown jewel” of the Almanor Basin, says Ryan Burnett, Sierra Nevada group director for Point Blue Conservation Science. The meadow’s three special-status bird species would get immediate attention from a private owner focused on conservation and the local community, he notes, “but conservation is not PG&E’s primary interest,” and no company representative is on site applying the vigilance the resources deserve.

The easements restricting PG&E’s activities in the meadow and at Lake Almanor itself are still being negotiated with the Feather River Land Trust. One issue in play is management of reservoir levels to support nesting areas for Clark’s and western grebes, which represent 5 percent of those birds’ worldwide populations, according to Burnett. The last two decades have seen multiple years when fluctuations in the water level managed by PG&E have caused complete grebe colony failure at Almanor. With these birds “front and center” as a conservation consideration, negotiating the terms of the easement with PG&E will be tricky, he says.

While protections at Almanor remain uncertain, conservationists and business owners alike are elated by the Stewardship Council’s accomplishments at Kennedy Meadows. At 6,200 feet, the 240-acre parcel is a gateway to the Sierra Nevada high country that includes 9,000-foot peaks in Emigrant Wilderness and northern Yosemite National Park. Although it was not a bargaining chip in the ownership negotiations, this is where Wild author Cheryl Strayed dumped her ridiculously heavy gear and learned to use an ice ax on her epic Pacific Crest Trail trek.

Kennedy Meadows was one of the first PG&E parcels the Stewardship Council tackled for transfer to a new owner. It took years, complicated by concern over the fate of Kennedy Meadows Resort and Packstation, a family-owned business that had a standing agreement with PG&E. No one wanted to lose this historic operation, which has been transporting visitors via pack-animals to campsites along the Sierra crest since 1917. But the Stewardship Council had no model for how to protect the business under a new owner. “We were in unprecedented territory,” says Art Baggett, Stewardship Council chairman originally appointed to represent the State Water Resources Control Board.

The solution transfers the property title to Tuolumne County, along with the pack station lease. Mother Lode Land Trust was involved “from the get-go,” says Ellie Routt, executive director of the organization, endorsing the new ownership and tasked with enforcing the conservation easement. The Kennedy Meadows transaction demonstrates the Stewardship Council’s commitment to protecting each parcel as it fits into the larger Sierra Nevada community, Baggett says: “We understand there’s a long history with First People and ranchers, loggers, and tourism. That’s all part of the community.”

Among the most celebrated of the PG&E ownership transfers are the 8,000 acres going to three Native American tribes. The Maidu Summit Consortium now enjoys the distinction of representing the first Mountain Maidu people without federal tribal status to have some of their ancestral lands returned. It will use seasonal burning and other traditional techniques to restore Humbug Valley in the Feather River headwaters near Yellow Creek. The Pit River and Potter Valley tribes are now owners of traditional homelands in headwaters of the Pit and Eel rivers. The Stewardship Council, which added a Native American representative to its original board, made a strong effort to include tribal input and solicit interest in land donations from tribal organizations, council executive director Heidi Krolick says.

Other Stewardship Council decisions recognize the changes a warming climate is bringing to California. Nearly 5,000 acres are being transferred to the University of California’s Center for Forestry, an extraordinary gift that nearly doubled the size of the center’s research forests. These acquisitions, near the Pit River in Shasta County and in the Lake Spaulding area of Nevada County, will allow scientists to study the effects of climate change on trees and wildlife. The university is working closely with Cal Fire on research to minimize the risks posed by wildfire, invasive species, and insect attacks on trees. Cal Fire will be the new owner of 15,300 acres of PG&E lands, the largest amount to be donated to a new fee title recipient.

Transforming lands that were idle assets into scientific study areas is a major benefit to the people of California, Krolick adds: “These transfers will help us understand how we can increase resiliency of these critical watershed areas and how that can be applied in California and elsewhere.”

Such indisputable accomplishments are clouded by disappointment over the limits on the amount of land made available for new owners. The promise of comprehensive conservation in exchange for bailing out PG&E was clear in the original bankruptcy agreement, Wayburn says: “PG&E was duly bailed out and moved on to do quite well. The public got some conservation, which is great, but it did not get what was envisioned.”

Stewardship Council members shared her frustration as they coped with the land available for new owners—a reduction from an estimated 88,000 acres to less than 44,000 acres. “I don’t think any of us went into this thinking that’s the way it would unroll,” says Soapy Mulholland, a Stewardship Council member representing the Central Valley Regional Water Quality Control Board.

Some parcels were of little interest to new owners due to remote location with limited access or being too steep for most usage, Krolick says. But most parties involved agree the decrease in available acreage stems from prior decisions about which lands are essential to PG&E’s hydro operations and which are not. Those determinations were made after the bankruptcy judge ruled and before the Stewardship Council began its work in 2004, at which point the specific tally was already solidified: 44,000 acres to new owners, 96,000 to PG&E.

Mulholland says PG&E officials found they needed more land for hydro operations than the original studies showed. Sutton cites legal impediments, including approval of transactions by the California Public Utilities Commission and FERC. Wayburn blames concessions to the utility company that, she says, put the Stewardship Council “under PG&E’s ultimate control.”

For all 100,347 acres that PG&E retains, conservation easements are held by 13 different organizations that range from Ducks Unlimited to Sequoia Riverlands Trust, with terms specific to each property. The easement holders, almost half of them responsible for multiple easements, are monitoring PG&E’s activities annually to ensure its compliance.

Still, having more land retained by PG&E means fewer of the 140,000 donated acres will receive the proactive conservation originally envisioned. New owners are by definition dedicated to climate change resilience and cohesive, ecologically oriented restoration. PG&E? Not so much. “With wildfire and financial balance sheets now taking precedence, I’m concerned that PG&E’s mindset is on a totally different track,” Tuttle says.

The long, drawn-out process has cost valuable time for species clinging to life. Willow flycatchers are declining rapidly and likely to go extinct in the Sierra in the next 30 or 40 years, Burnett says. A conservation-minded owner might have brought more rapid and consequential action to save this species.

Meanwhile, on lands PG&E will eventually relinquish, the 16 years it has taken the Stewardship Council to recommend new owners has deprived sensitive areas of much-needed protective attention. PG&E has continued to manage these ecosystems, in some cases “high-grading” forests for timber and other natural resources, Wayburn says, which has stalled restoration and research that might otherwise have been well underway.

Paul Moreno, a PG&E spokesman, defended the land transfer process as the largest undertaking of its kind. “While giving away land may seem like an easy undertaking,” Moreno says, “the land comes with specific conditions and conservation easements that prohibit development and ensures public access and benefit, so the lands need to be actively managed.”

Despite the delays, the Stewardship Council’s work was nearing its final stage when PG&E entered bankruptcy court once again in January 2019. That threatened to derail the process. But the bankruptcy court issued an order authorizing PG&E to maintain and administer “customer programs,” including its 2003 land conservation commitment. It was a ruling PG&E sought, Moreno says. Governor Gavin Newsom’s proposal for public takeover of PG&E might also have disrupted the incomplete land transactions, but in March he and the utility reached an agreement that should allow the company to exit bankruptcy by the June 30 deadline set by the state. PG&E can still sell the lands it is keeping under the 2003 bankruptcy settlement, but future landowners would be subject to the conservation easements it requires, Krolick says.

However these agreements play out on the ground, the process of assigning new owners and conservation easements to PG&E lands has demonstrated the value of engaging a broad spectrum of interests. The Kennedy Meadows community will keep its pack station and its wet meadow because of the wide-ranging conversations that led to the Tuolumne County ownership. Chester Meadows would benefit from similar local input. The Stewardship Council process also offers a lesson in timing. The public lost interest in some land transactions, which dragged out for over a decade.

The bankruptcy agreement is a cautionary tale fraught with frustration over lost opportunities and an extraordinary outlay of public time and money. Still, it leaves California and its citizens enriched by 140,000 acres of precious forests and wetlands, protected from development now and for all time. With new owners promising to restore fully functioning ecosystems, those earlier disappointments should point the way to speedier, more resolute negotiations in future conservation deals. The lands deserve no less. υ