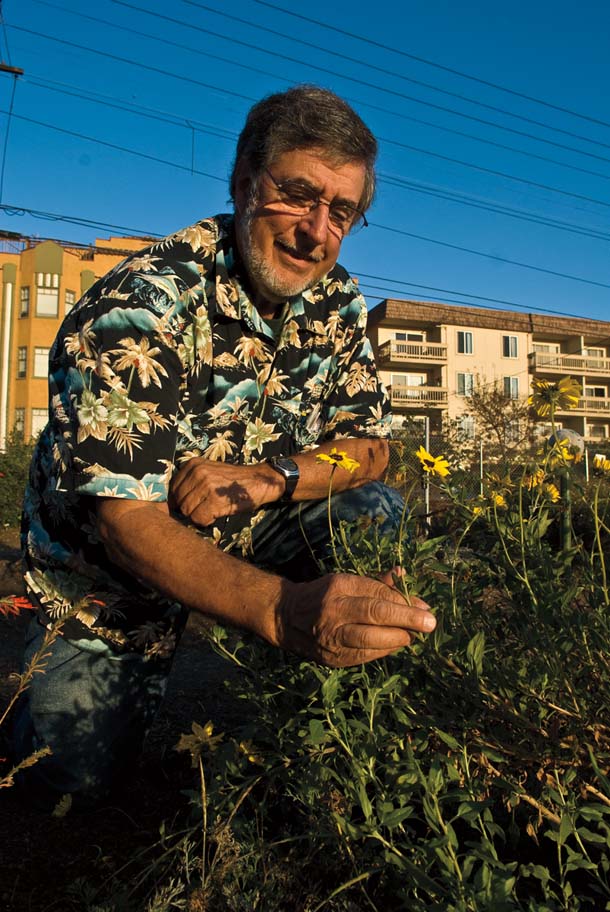

Gordon Frankie doesn’t look like the guy who is about to change your life. When you first see him, chances are he is wandering down your street, idly peering into your neighbor’s yard, wearing a goofy half-buttoned Hawaiian shirt and carrying a floppy white net.

Consider locking the door. Shutter the drapes if you have to. Whatever you do, don’t go out and ask him what he is doing–you may never be able to look at your garden the same way again.

Frankie is a UC Berkeley professor and a native bee expert. Bees are his unmitigated passion. But before you walk out the door to talk to him, drop anything you think you know about honey-making hive-dwellers. For him, the most important bees are the ones you probably see every day–but have never heard of.

- Bee researcher Gordon Frankie in his urban bee garden in Berkeley. Photo by Stephen Spiker.

For most people, the word “bee” means the European honeybee–a medium-size semifuzzy black-and-yellow bug with an angry barbed stinger. Honeybees live in giant hives, make honey out of nectar, and are almost exclusively female. It turns out that none of the 1,600 known species of native California bees are anything like these transplants from across the Atlantic. Our homegrown bees can be green, black, or even red. They range in size from giant bumblebees to some that are barely visible to the naked eye. Some are as furry as a Sasquatch. Others are smooth and metallic. They mostly live alone or in small groups, sleeping in burrows or bivouacking on flowers at night. They are roughly split between male and female, they don’t have queens, their stingers don’t get stuck in your skin, and, lastly, they don’t make honey.

In fact, native bees in California really don’t have much in common with honeybees beyond one crucial similarity: their hunger for nectar and pollen. As with the honeybee, their search for food takes them from one bloom to another, facilitating the fertilization of millions of farm fields and gardens across the state. As honeybee populations continue to crash, scientists are looking to native pollinators to pick up the slack in maintaining our agriculture and helping our gardens to bloom.

The only questions left: Are they up to the task? And how can we help?

“Put your hand right there. It’s okay.”

- A male Melissodes robustior with its characteristic long antennae. Males of this species spend the day chasing each other around but they may later cluster on flowers or stems to sleep. Photo by Rollin Coville.

Frankie, several researchers from his lab, and I are in the small plot of ornamental plants that he and his staff maintain as a bee observatory in a corner of UC Berkeley’s downtown research gardens. He is positioning my thumb and my middle and index fingers into a little tripod with one hand, holding a small bee with the other. “I want you to hold him with three fingers. Here. Go easy now, don’t forget, this is a little tiny guy. If you get spooked, you can let it go,” Frankie says.

- Many bees, like this female Melissodes robustior, carry pollen on their legs. Solitary females gather pollen to create food stores on which they lay their eggs. Photo by Rollin Coville.

Though I am roughly a million times bigger, I’d be lying if I said I wasn’t spooked about having an angry-sounding live bee in my hand. However, Frankie has a lot of experience with people’s bee phobias. Over the past few years he has become something of an apian apostle, writing countless articles and giving dozens of talks about bees. Over the phone, Frankie seems meek and soft-spoken, like a small-town deacon or an academic recluse. The image doesn’t fit in person, however. A tall, broad man with powerful hands, he’s quick to laugh and mixes powerful charisma with wide-eyed childish fascination. I quickly see why some people who know him call him “the Johnny Appleseed of bees.”

He gently places the bee between my three fingers and I clamp down while trying not to squash the poor thing. As I expected, the bee is buzzing angrily–so hard I can feel it all the way down my wrist. But Frankie assures me that I won’t get stung; a bee stinger is a modified egg-laying organ and this bee is a male (hence, no stinger).

- Female squash and gourd bees like this one are rarely found on the flowers of any other plants. Indeed, these bees are far more effective than are honeybees at pollinating squash and related plants. Photo by Rollin Coville.

It’s a captivating experience, once I get over my fear. This particular bee is called a leaf-cutter bee and I am struck by just how appealing the little fella is. It’s similar to a honeybee, but smaller and darker, with light-colored fuzz on its thorax, furry little legs, and googly eyes. Leaf-cutter bees nest in small holes that they line with leaf bits, precision-cut into slices. If you see a bee lugging a leaf chunk twice its size through the air across a garden, you’ve got a leaf-cutter.

The furry little bug crawls around a bit until I can’t stand the vibrations and have to let him go. Frankie is clearly enjoying watching a newly baptized bee lover. Suddenly I have all kinds of questions for him. I learn that leaf-cutter bees, like all bees, mostly eat sugary nectar. The protein-filled pollen they collect is for their young. The pollen is mixed with nectar and wrapped in leaves along with an egg in a burrow to nourish the larva as it grows. Leaf-cutters are widespread but especially sensitive to drought and the young may wait as long as three years to emerge from their burrows, depending on rain. In the desert, other bee species may wait over a decade for a good enough rain to emerge.

Listening to him, I see the dual charm of Frankie and his bees. He sees each bee species as a kind of story that he tells with relish.

Take the “head-bonker” bee. More commonly called the wool carder bee, this little degenerate picks a single plant, like gumplant or woolly bluecurls, and just hovers above it all day, to save all the nectar and pollen for itself. Any bee, regardless of species, that tries to stop by for a snack gets bombarded and chased off. The head-bonker is not very big, but it’s got moxie. Frankie loves to tell of one particularly self-deluded bee that head-butted a researcher between the eyes.

Thanks to stories like these, most visitors to Frankie’s garden soon find themselves hunched over, squinting at the shrubbery. It’s an obsession that Frankie discovered at age 15. One summer when he was beaten out for a job as a Boy Scout naturalist by a kid who knew about bugs, Frankie got stuck washing dishes. Out of curiosity, he began collecting bugs. From then on he was hooked on anything with six legs and an exoskeleton. He lost his dishwashing job after repeatedly coming in late because he was looking for beetles under logs. He went home to Albany and then straight to Wellman Hall at UC Berkeley (the building where he now works) to meet other entomologists.

- Another Tilden denizen, a female cuckoo bee of the genus Nomada. Cuckoo bees bypass the chore of gathering pollen and instead lay their eggs in another bee’s nest. Photo by Rollin Coville.

Forty years on, Frankie still has that boyish fascination. Wherever he goes, he rarely takes his eyes off nearby plants. A few years ago Santa Cruz resident Kimberly Gamble discovered him snooping around her front yard, where she has a number of native plants. She came out to find out exactly what he was doing there. Frankie, charming as ever, complimented her on her pollinators and began extolling the virtues of native bees. Eventually she invited him to see the larger garden at her second house just outside town. It wasn’t long before she agreed to host a small number of native-bee-attracting plants herself. Then she agreed to more. And then more.

“He’s so committed and enthusiastic that it just rubbed off on me. I really appreciate those passionate people who are really knowledgeable about something,” she says. “He’s one of those quirky kinds of guys.”

- The male wool carder bee is also known as a head-bonker. It aggressively defends a chosen plant, chasing away all other bees who might hope to grab a little nectar or pollen. Photo by Rollin Coville.

Gamble says that before she met Frankie, she was very particular about her landscaping. In contrast to Frankie’s haphazard research plots, her sprawling 12,000-square-foot garden overlooking the Santa Cruz coastline resembles something out of House Beautiful. Yet almost everything in it is there to attract bees. She says Frankie started out slowly, recommending a gumplant here, offering to deliver some seaside daisy there. Eventually, she fell in love with the visiting bees as much as with the flowers themselves. She admits that she doesn’t know all their names, nor the names of all the plants Frankie now hauls in every few months. However, she says most of her gardening decisions are “Gordon influenced” and while she’s still very particular about her garden, she’ll plant whatever he asks. She says her garden is her meditation, and the bees are part of that. “Watching bees, you can’t really hurry that,” she says. “Now I am at my little grandson’s speed.”

- A female leafcutter taking time out to rest or rearrange her load on her way back to her nest, which she’ll line with precisely clipped bits of leaves and other material. Photo by Rollin Coville.

Of course Frankie is more than happy to suggest new plants to prod her along. Her property is now his active research site, shedding light on a group of creatures still largely in the dark. Although scientists have studied the European honeybee for centuries, much less is known about our native bees. Scientists know roughly how they live but less about specifics like what flowers they prefer and why. Partly it’s a numbers game; after all, there are hundreds of distinct Northern California native bee species and only one honeybee. Partly it’s because few organizations want to bankroll research they don’t think is directly useful to farmers.

But today, as honeybees are hobbled by one plague after another, scientists are becoming interested in the role natives play in pollination. The latest plague to grab headlines, Colony Collapse Disorder (often called CCD), is characterized by a sudden disappearance of all or most of the bees in a hive. Researchers are still unsure how widespread the problem is or what might be causing it, but they suspect it may be a combination of parasites and pollution. Some scientists have suggested that CCD is largely the result of packaging bees up in boxes and driving them across the country from one pesticide-laced field to the next.

There is, however, one thing that we know about CCD: Whatever the mechanism, whatever the vector, it doesn’t seem to affect native bees.

- Kimberly Gamble’s garden near Santa Cruz has become a testing ground for Gordon Frankie’s bee-friendly practices. An enthusiastic convert, Gamble has happily let Frankie influence all her planting. Photo by Kimberly Gamble.

Ask Frankie which bee species is his favorite and he vacillates wildly. You might as well ask his favorite food or song. However, eventually he settles on the blue orchard bee. “BOB,” as he calls it, is a shiny metallic black or dark blue bee that nests in muddy soils throughout much of the United States. As the name suggests, it frequents orchards, including almond orchards. This fondness is especially interesting because commercial almond orchards are almost totally dependent on honeybees and have been hit hard by hive collapses.

Orchard bees are an order of magnitude more effective as pollinators than honeybees because they carry their pollen on their abdomens rather than on their legs. As they visit each flower, the abdomen scrapes around, dumping pollen all over the place. In addition, early data suggest that rather than competing with honeybees, orchard bees may actually help make them more efficient. So why aren’t orchard bees the main pollinators in almond orchards? For one thing, these bees nest underground, so they don’t travel well. For another, they’re solitary and hard to organize. But farmers can help the orchard bees already in an area by putting aside a little (preferably damp) land nearby, so the bees have a safe place to nest.

- Male of the “ultra-green bee” featured on the opening image of the article. Photo by Rollin Coville.

While native bees don’t seem to be affected by CCD, they do have other worries. Robbin Thorp, a well-known bee specialist at the UC Davis, is one of Frankie’s many collaborators. Thorp has something of an academic crush on bumblebees and often uses phrases like “handsome little bee” to describe his favorites. He says that in addition to any diseases their European cousins bring, native bees have to contend with all kinds of pesticides, which are indiscriminate in what they kill. While a few people have looked at the effect of sprays on adult bees, Thorp suspects the sprays bring down a whole suite of unknown impacts on larvae. That, coupled with habitat loss, has been causing native bee populations to dwindle long before CCD landed on the front page.

- Carpenter bees, California’s largest bees, are up to an inch long. Female carpenter bees drill nests in wood. Photo by Rollin Coville.

A few years ago, Frankie began to wonder if urban gardens could form a patchwork reserve for bees losing out to pesticides and development in the hinterlands. At first, many of his colleagues thought he was wasting his time. There simply weren’t enough native plants in backyard gardens to sustain the bees.

“When we started, there were entomology colleagues of mine who didn’t believe there was anything to this,” he says. “Then when we said, ‘Hey look, we’ve got 75 species of bee in Berkeley,’ people said, ‘What?'”

- Some bees, like this Megachile perihirta, gather pollen on their abdomens; others store it on their legs. Photo by Rollin Coville.

Native bees apparently are not as picky as people thought. Frankie now believes that urban bee gardens are a treasure trove of bees that could buttress struggling wild populations–which could in turn aid farmers. Bee gardens, similar to butterfly or hummingbird gardens, can be any size and should include mostly native plants. Frankie has started a website advising gardeners what plants best attract bees. Bee gardening has been slow to catch on so far, possibly because of people’s fear of bees, but for those who have tried it, it can be addictive.

Take one of Frankie’s most dedicated disciples, Sue Holland. Holland teaches biology at Miller Creek Middle School in San Rafael. Her classroom is a wonderful collection of biological knickknacks. There is a cabinet full of bones and pickled specimens, student-delivered road kill (“Other teachers get flowers and candy, I get dead stuff,” she says), and a surly-looking python named Hot Lips.

She went to a talk Frankie gave and at the end, when he asked for volunteer bee gardeners, her hand shot up. Now she’s hooked.

“It’s an obsession. You just can’t stop it,” she says.

Originally, the little plot behind her classroom was just a normal garden. Frankie started suggesting bee-friendly plants and when the plants arrived the bees were literally waiting in the parking lot. They followed her into the garden and have been there ever since.

- Sitting on the photographer’s finger, this tiny Ceratina acantha is just a fraction of an inch long. Photo by Rollin Coville.

Today, her eclectic 600-square-foot garden of poppies, ceanothus, and native sunflower has grown several feet over her head in places and is rich with birds, bees, lizards, and spiders. Everything is hand watered and there is no mulch (Frankie hates mulch and rails against it at every opportunity because it inhibits burrowing). Bees have worked their way into many of Holland’s lessons on evolution, anatomy, and behavior. Her students draw pictures of bees, count them, and sometimes just sit and watch them. Holland spends hours watching bees in nurseries for ideas on new plants she might use. She can identify the native bees at least as well as any of Frankie’s graduate students and has compiled an extensive collection of mounted bees, each meticulously pinned and labeled.

And in the garden’s six-year life span not one student has been stung.

Back in his office, the Johnny Appleseed of bees beams as he talks of the half dozen backyard research sites around the state and about the bees that live in them. He says once people know about bees, they can’t help but watch them.

“You say, ‘Look at what that thing is doing–it’s so interesting.’ And then you see another one and it’s doing something different. And then you see another one and it’s doing something different,” he says. “And then you start telling people about them, and they say, ‘Really? I thought that was a fly.'”

Certainly Kimberly Gamble is hooked. She’s watching a new house being built down the street. As soon as her new neighbors are settled, she says, she’s going to introduce herself–and suggest a guy to help them with their garden.

You can see Frankie’s garden as part of the Bringing Back the Natives Garden Tour, a free event on May 3. Register at www.bringingbackthenatives.net. Keep an eye out for Frankie’s upcoming book on how to start a bee garden, or check out nature.berkeley.edu/urbanbeegardens or www.pollinator.org.

.jpg)