Beneath the shade of bigleaf maples, bay laurels, and valley oaks, I rest beside a natural spring near the caved-in mouth of Day Tunnel. The mile or so hike up the Randol Trail—a wide dirt path that the Mexican and Cornish miners who once worked here knew as Metal Road—has left me sweating on this unseasonably warm winter day. Still, it’s much cooler than hiking here in summer, when fierce midday heat often blankets the hills of Almaden Quicksilver County Park. Rain-bearing cumulus clouds are gathering on the horizon, promising more seasonally appropriate weather soon.

A deer mouse, one of five mice species living in the park, pokes through the leaf litter by the water. Generally nocturnal, deer mice typically build their nests in small, dark tunnels that they periodically excavate, sometimes several times a year.

Mice aren’t the only creatures to have dug holes in the ground of this 3,977-acre park, tucked into the foothills of the Santa Cruz Mountains. The stories of the other burrows, the holes not dug for shelter, draw us into the fascinating human and natural history of this place.

Thirty miles of trails take walkers, equestrians, and cyclists through a hilly mosaic of grasslands, oak woodlands, and chaparral. The occasional dilapidated shed, the remains of a 70-foot brick chimney perched on the hill, a fenced-off ore furnace, and rusting pieces of machinery woven with poison oak vines indicate past human activity. If it weren’t for the explanatory signs, however, park visitors would never guess what’s hidden below the ground: more than 54 miles of man-made tunnels, shafts, and cavernous rooms—some big enough to hold a three-story building—cut and blasted from solid rock.

Why all the burrowing? The Ohlone Indians, who lived here for several thousand years before the arrival of the Spaniards in the 1700s, first started collecting the vermilion nuggets that they found in a nearby cave. They called the prized rock mohetka (red earth) and traded it with coastal tribes from as far away as Puget Sound. Mohetka was ground into a fine powder, mixed with water, and used as a body paint.

Ohlone folklore, however, hints at the rock’s dark powers. In the mid-1800s, the Indians who came to these hills to gather acorns and hunt black-tailed deer, quail, and other animals told Spanish missionaries of a group of Ohlone ancestors who became deathly ill after painting themselves with mohetka. Most of the village would have perished but for the serendipitous appearance of a black-robed female spirit, who advised the people to bathe in a spring. After drinking and washing in the waters, all were healed, surviving to leave behind the first local account of a disease more associated with the industrial era—mercury poisoning.

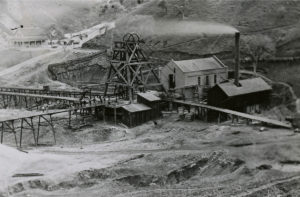

- Two miners work at a seam while a third carts away a load of cinnabarore (undated). Courtesy of the New Almaden Quicksilver Park Association

Andres Castillero, a Mexican cavalry officer schooled in mineralogy, traveled through the area in 1845, and guessed at the local rock’s modern-day significance. He dusted the Indian’s red powder onto hot coals, then sprinkled the coals with water and collected the steam in a glass tumbler. When he saw tiny beads of quivering silver mercury (the same liquid metal used in household thermometers) clinging to the glass, he must have been quite happy. The Mexican government had a long-standing reward of $100,000 for anyone who discovered a workable mercury deposit in the New World, and Castillero had just stumbled upon the world’s fifth largest deposit of cinnabar, the scientific name for the bright red ore of mercury.

Many millions of years ago, violent geologic forces warped and cracked the land that would become the California coast. An uplifting body of rock that originated beneath the Pacific Ocean helped create these hills. Modern geologists call the Coast Range’s unique and tortured mix of sedimentary, metamorphic, and igneous rocks the Franciscan Complex. One component of the Franciscan Complex is serpentinite (the California state rock), a blue-green rock consisting of material scraped from the earth’s mantle and then scoured and squeezed up to the surface by plate collisions. On its way up from the depths, some of the serpentinite was chemically altered further by intense pressure and moderate heat. The resulting harder metamorphic rock is called silica-carbonate, which formed a type of crust—up to 40 feet thick—around large bodies of serpentinite. Starting about 12 million years ago, superheated water fromdeep underground began circulating through fissures in the silica-carbonate. The water carried traces of mercury and other minerals, which were deposited over eons in these fractures, sometimes even replacing the surrounding rock. When cooled, these deposits formed cinnabar.

Several million years later, this ore became extremely valuable; mercury—or quicksilver as it was sometimes called—was an essential element in the process used to refine and purify gold and silver. So demand for the liquid metal in the New World was astronomical, and hence the significance of Castillero’s find. However, Casterillo never collected his reward; less than a year after his discovery the United States declared war on Mexico and, three years later, took possession of California.

By 1854, with the California Gold Rush in full swing, the New Almaden mine (named after the famous mercury deposit in Almaden, Spain) was a substantial operation. Thirteen brick furnaces operated continuously in a meadow by Los Alamitos Creek at the south end of Metal Road, near what is now the Hacienda staging area. Superintendents and mine managers lived near the meadow in handsome cottages, while most of the Mexican and Indian laborers had shacks in the quickly constructed community of “Spanishtown” at the top of Deep Gulch, overlooking the furnaces.

- Natural spring across from the closed-off entrance to Day Tunnel. Photo by David Weintraub

Known as Hacienda de Beneficio, the reduction works roasted top-grade cinnabar, composed of 76 percent mercury and 14 percent sulfur. Tiny streams of mercury, condensed from the cooled fumes, poured day and night into iron flasks, each flask containing 76 pounds of mercury worth $45, a great sum in the 1860s. The nonstop furnaces were fueled by oak and madrone cut from nearby woodlands.

Across the path from where I sit at the entrance of Day Tunnel, a tremendous mound of grayish rocks spills down the hillside. The miners passionately hated this blue-gray stone called alta. Formed in the fracture zones where serpentinite ground up against the surrounding sedimentary rocks, alta is a poorly consolidated mixture of the two rocks. Heavy, wet, and prone to caving in without warning, its presence around cinnabar deposits was a constant source of trouble for the miners here.

Indeed, the miner’s life was seldom easy. Most worked an 11-hour shift, six days a week. They chipped at the tunnel’s stone face by flickering candlelight, using only heavy sledgehammers and hand-held drill chisels. The stench of blasting powder would fill the pitch-black tunnels and excavated rooms (stopes). Temperature in the deeper digs, 600 feet below sea level, hovered around 100 degrees Fahrenheit with 100 percent humidity. “It’s as close to hell as any good Christian would want to get,” wrote one miner. Prior to the introduction of ventilation and stricter safety procedures in 1863, an average of four miners died each year of mercury poisoning.

By that time, an influx of Cornish miners had joined the Mexicans on Mine Hill, building a village known as Englishtown a short distance from the reduction works. Much oak woodland was cleared for stores, a schoolhouse, a graveyard, hundreds of cabins, and domestic flower gardens. By 1901, there were more than 700 buildings associated with the mine. In the peaceful quiet that fills this place now, it’s easy to forget that, in its heyday, New Almaden’s mine operations employed upwards of 2,500 people (10 percent of the population of Santa Clara County), more than 1,000 of them underground.

A century later, nature has regained the upper hand. Only a few structures, in advanced stages of decay, remain. Yet I sometimes come across a brilliant patch of horticultural irises or a light pink rosebush growing in a wild field. More than 100 native flowering plants blossom in Almaden Quicksilver Park—in springtime the landscape is saturated with color—but these two floral species were introduced by miners’ wives.

From the top of Mine Hill, I take in the magnificent view north and east toward San Jose and across the Santa Clara Valley to the Diablo Range and Mount Hamilton. Behind me, to the west, the tree-cloaked ridges of the Santa Cruz Mountains crowd the horizon. Surrounded by such expanses, it is hard to imagine traveling deep down in a pitch-black man-made tunnel, just a few hundred feet below.

- California brown tarantula beside the Randol Trail. Photo by Scott Hinrichs.

While the miners are long gone, other creatures still dig into the hillsides here. Besides the deer mouse, cottontail rabbits, ground squirrels, pocket gophers, and moles riddle the park with their warrens and burrows. I often discover shrew holes under the oaks in the broken grass beside the trails. A few weeks ago, in the late fall, I noticed a California brown tarantula secreted inside the entrance of an abandoned gopher burrow. Early winter marks the end of this arachnid’s breeding season. Many male tarantula spiders wander the leaf litter along the park’s trails in search of mates, while the females linger in burrows awaiting suitors. This female was still waiting for a male tarantula to arrive and impregnate her, whereupon she would try to devour him. More proof that tunnels are often dangerous places.

Some of the park’s reptilian population—including king snakes, gopher snakes, and rattlers—also crawl into deserted animal burrows for shelter. Indeed, during the early days of mining here, cinnabar haulers tossed rocks into the mine tunnels and then listened carefully for a rattlesnake’s warning buzz before entering.

Mining continued here through much of the 20th century, even though the cinnabar ore bodies had largely been exhausted by 1905. By that time, other methods had been invented for purifying gold, but mercury was still used to make caustic soda and as a catalyst for industrial processes. The two World Wars elevated the demand for quicksilver; the large, open quarry on the southwest side of Mine Hill was excavated during World War II. The rock dumps, where 19th-century miners had tossed lower-grade ore, were salvaged for the remaining quicksilver. Pools of spilled mercury were unearthed under the reduction furnaces.

Then in the 1970s, reports documenting the dark side of mercury began to appear. Life magazine published a chilling photo-graphic essay showing Japanese children born with terrible birth defects because their mothers ate mercury-laden fish. The bottom quickly dropped out of the mercury market. Wary of class-action lawsuits, chemical companies quit using the metal altogether. No longer was the once precious red ore worth pulling out of the earth. But before shutting down for good in 1975, the New Almaden mine produced over $60 million worth of mercury, equivalent to $3 to 5 billion in today’s dollars.

- View northeast from Mine Hill towards Sunnyvale and Mountain View at night. Photo by Scott Hinrichs.

Recognizing the area’s historical value, Santa Clara County Parks purchased the area—with its seven abandoned mine sites—in 1975. One hundred or so tunnel and shaft openings were closed off, and the meadow where the reduction works formerly stood was cov-ered with three feet of clay soil. After much remediation, Los Alamitos creek once again runs clear, its banks thick with maple, sycamore, and other riparian vegetation. Yet signs warning people not to eat any fish caught in the creek indicate that past damage can cast a long shadow.

- Ben Pease

As I return down Metal Road, the rain begins to fall gently. Most of the cinnabar nuggets have been taken from the mine dumps and roads; the rocks visitors encounter today are mostly silica-carbonate, serpentinite, chert, greywacke, and alta. But still my eyes scan the ground as I walk. In the fading winter light, the rain washes the dust from a chip of rock, revealing its bright red surface; a small piece of rock with a large legacy.

Getting There:

By bus: Valley Transit #13 runs from San Jose to the town of New Almaden near the Hacienda park entrance. For route and times, call 817-1717 (no area code) or visit www.transit.511.org.

By car: From Highway 85 in San Jose, take the Almaden Expressway exit and go south 4.5 miles to Almaden Road. Proceed 3 miles on Almaden Road through the town of New Almaden. The park headquarters and newly renovated museum are located in the Casa Grande about a half mile before the unpaved Hacienda parking area and trailhead. Maps and literature are available there.

.jpg)

-300x221.jpg)