The looming bulk of Mount Hamilton is a familiar sight to anyone driving Highway 101 through the Santa Clara Valley. At 4,196 feet, it’s the tallest peak visible from the shores of San Francisco Bay, identifiable by the stark white globes of Lick Observatory at the summit. But despite the mountain’s impressive dimensions, many Bay Area residents know little about the wildlands and working lands it encompasses. This is the most expansive wild landscape in the Bay Area: roughly 700,000 acres of public parks, university and conservancy reserves, and private ranches. It stands as a bulwark of wildness between the highly developed communities to the west and northwest and the intensively cultivated croplands of the San Joaquin Valley to the east.

From atop one of the higher hills on the University of California’s Blue Oak Ranch Reserve, the story of the region comes into focus. Above, to the southeast, are the observatory buildings at the top of the peak. Almost directly below, to the east, is the dizzyingly steep canyon of Arroyo Hondo, its year-round stream cooled by a lush riparian forest. Groves of valley and blue oaks cloak the surrounding slopes, and wildlife is abundant: Mountain lions, bobcats, and coyotes hunt here, and so do rarer predators such as San Joaquin kit foxes and badgers. This is essential habitat for both raptors and songbirds, and a wide array of native reptiles and amphibians are found here, including protected species such as California tiger salamanders, California red-legged frogs, and western pond turtles. San Diego State rattlesnake specialist Rulon Clark has opined that Blue Oak Ranch has the state’s densest population of northern Pacific rattlesnakes.

Look west, though, and the vista is utterly, jarringly different: The sprawling high tech campuses of Silicon Valley and the spires of downtown San Jose dominate the far and middle distance, and tracts of e-suburbia lap right up against Mount Hamilton’s lowest slopes.

And then there’s another, less visible, factor that compounds the threat to this magnificent ecosystem: climate change. Warming global temperatures, shifting precipitation, and drier soils may well disrupt Mount Hamilton’s ecological equipoise, perhaps eliminating entire suites of native species. Mount Hamilton and the surrounding wildlands of the Diablo Range are hardly unique in this regard; around the world, most landscapes are feeling im-pacts from spiraling greenhouse gas emissions. But Mount Hamilton is more than just another “victim” of a warming planet: It is pointing the way to effective response strategies. Researchers are using the surrounding landscape as a living laboratory to develop methods for conserving native plants and animals in an era of profound climate change.

The mountain has been the focus of a long-term conservation project for the Nature Conservancy: Since 1997, in partnership with agencies, landowners, and other organizations, the conservancy has helped protect about 115,000 acres around the mountain and surrounding Diablo Range through land acquisitions and con-servation easements. Along with the 200,000 acres protected by public agencies, these deals go a long way toward preserving an essential reservoir of biodiversity at the edge of the densely populated Bay Area.

But as acknowledged in a 2011 report by Nature Conservancy researchers, the organization’s original conservation strategy of simply preserving wildlands might be insufficient to address the challenges of climate change. Properties were acquired on the assumption that resident native species would be protected in perpetuity. But what if changing climatic conditions meant that even protected landscapes were no longer suitable for those target species? Given that Mount Hamilton already was the focus of one of the organization’s most ambitious conservation efforts, it made consummate sense to investigate the im-pact global warming might be having on the mountain’s ecosystems–and start figuring out what to do about it.

“The original conservation plan looked at Mount Hamilton as a basically static system,” observes Sasha Gennet, the conservancy’s Central Coast ecologist. “But climate change has altered that. Natural communities are in a state of dynamic flux, in-creasingly so due to climate change. So conservation plans have to be flexible and aim at long-term goals that maximize the options for wild species.” That sounds straightforward enough, but the devil is most definitely in the details. It’s not just a matter of figuring out what to do for Mount Hamilton: The goal, Gennet emphasizes, is to develop streamlined, standardized protocols and methods that can be used as conservation planning guidelines for other areas threatened by climate change. “We’re realizing we need better–quicker, cheaper, more accurate–means of assessment,” Gennet says. “That’s what’s really driving our work here. As the effects of climate change become more pronounced, we’ll need cost-effective, reliable ways to evaluate and deal with them across a variety of landscapes.”

Several factors make Mount Hamilton ideal for such efforts. First, it has dramatic topographic range and variability, climbing from near sea level to more than 4,000 feet. The result is a wide variety of microhabitats, providing potential refuges for resident species that may become stressed by climate change. Then there’s UC’s Blue Oak Ranch, a 3,260-acre reserve on the northwestern flank of the mountain that draws wildland ecologists, zoologists, hydrologists, and climatol-ogists from several campuses, including Berkeley. And finally, there’s the mountain’s proximity to Silicon Valley–something of a blessing and a curse: McMansions spawned by the valley’s digital industries sprout on the lower slopes of the range and are a direct threat to its wild systems. Yet the valley is also a source of the funding and high-tech know-how helpful to such an ambitious conservation project.

Currently, much of the research at Blue Oak Ranch centers on a recently installed network of wireless sensors, explains Michael Hamilton, a conservation biologist and the director of the reserve (no relation to the Presbyterian pastor Laurentine Hamilton, for whom the peak is named). Hamilton, an ebullient man with a long white ponytail, conducts his work from a refurbished barn that serves as the reserve’s workshop, kitchen, meeting room, and sleeping quarters. Picnic tables accommodate both diners and equipment repair projects–sometimes simultaneously.

“This is our standard sensor unit,” Hamilton says, picking up one of the devices; it has the dimensions of a size 10 hiking boot. “It’s solar operated and works well in very low light. Actually, it’s designed to provide agricultural data–you put it in a field, and it relays information on temperature, humidity, solar radiation. But it’s ideal for our purposes too.” He flips it over and points out several ports on the bottom of the device. “You can plug in auxiliary sensors for soil temperature and soil moisture. We even have a sensor that functions as a kind of virtual leaf–it records condensation values, giving us an idea of the rate of condensation on vegetation in the wild.”

Researchers are also using small weather stations and automatic digital cameras to augment their database. Together, the technologies are beginning to provide a detailed picture of the effects of climate change on the mountain, at a fraction of the time and cost of more traditional research methods.

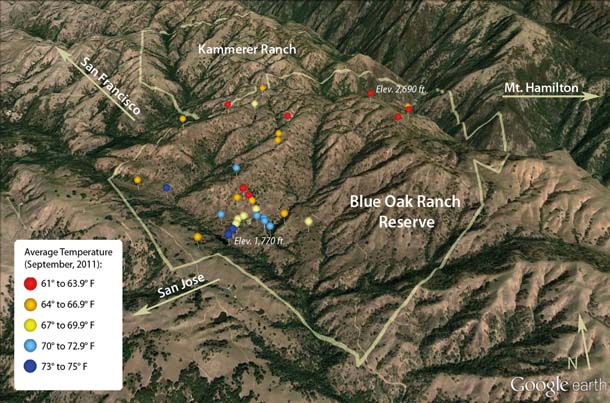

Hamilton logs on to his laptop and calls up a topographical rendering of Blue Oak Ranch. Sixty sensors appear on the map, strategically placed to capture the property’s range of conditions; all of them, explains Hamilton, transmit their data in real time to a central research station. He retrieves temperature information for the preceding 24-hour period on one of the sensors and displays it as a graph: The lines show a 30-degree variance between midday and nocturnal temperatures. That’s heartening, emphasizes Hamilton. “That shows the impact of the marine layer,” Hamilton says. “We like to see that. Coastal influence helps mitigate climate impacts. The greater the temperature range, the more potential there is for adaptation. We still have those cooler niches here that native plants and animals can exploit.”

A major goal of the work at Blue Oak Ranch is tracking ecotone shift–the movement of micro-habitats across the landscape as a result of climate change. At a shallow swale about a mile from the barn, UC Berkeley ecohydrologist Sally Thompson explains how changes in water availability–along with other variables, including shifts in solar energy–affect ecotone distribution. To the west of the swale is a slope covered with coyote bush merging with deep woodlands. To the east are sparse blue oak savannah and open grassland. The swale itself is damp and heavily thatched with grass. “Right now we’re in the aspirational stage of data collection,” explains Thompson with a laugh. “We’ve just begun, really. But we’re looking for the cutoff points for the various ecotones, and what determines them.”

Water distribution isn’t strictly a matter of rainfall; as Hamilton noted, the marine layer is also a factor. Fog deposits a great amount of water on foliage, and hence plays a major role in coastal ecotone distribution. “A very good indicator for the limits of the marine layer in this part of California are the epiphytic lichens–the gray-green hanging ‘moss’–on the oaks,” observes Thompson. “Here at Blue Oak, the cut-off point for these lichens is right around 1,800 feet. Above that, there’s little fog, and the ecotone distribution changes dramatically.”

Ultimately, says Thompson, researchers will combine marine layer information from different sources: the Blue Oak Ranch sensor arrays, photo sequences from cameras mounted at Lick Observatory, Doppler radar records from the San Jose Airport, and the monitoring of lichen distribution. “The goal, of course, is to use the data to arrive at predictions of how ecotones will move under certain conditions,” says Thompson. “And from that, we hope to derive timely and effective conservation strategies for specific species.”

In fact, lessons are being applied at Mount Hamilton even as they’re learned. Gennet points to the California tiger salamander, a federally listed species that is also one of the conservancy’s six target species for its climate adaptation work. The six-to eight-inch-long amphibian depends on grasslands with seasonal pools for its larval stage, and on ground squirrel burrows for use as refuges during the dry summer months. On Mount Hamilton, as in many other places in the salamander’s range, these requirements are most often met in rangeland with its attendant stock ponds.

Not surprisingly, it is the need for surface water at the right temperature at just the right time of year that makes the tiger salamander most vulnerable to climate change. According to Gennet, one of the leading causes of the decline of tiger salamanders has been poor water management practices on rangelands. So gathering data on how water moves through the ecosystem–as Thompson is doing at Blue Oak Ranch–is critical to the development of climate-adapted management practices for rangeland ponds: where to site them, when to dredge them, how to address surrounding vegetation, and so forth.

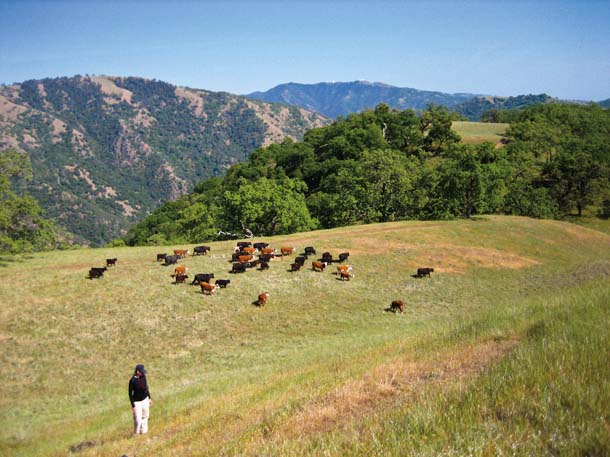

A serendipitous adjunct to the research at Blue Oak Ranch is the conservancy-owned Kammerer Ranch next door. Kammerer is still being grazed; Blue Oak is not. Comparing data from ponds on each will help researchers further refine their recommendations for maintaining stable California tiger salamander populations in the face of climate change.

While the warming climate is requiring scientists to adjust their conservation strategies, it has not affected their basic mission. “Climate change is requiring us to approach our projects in new ways,” explains Gennet. “But the goal remains the same: preserving biodiversity and all of its benefits for both people and wildlife.”