Now that the winter rains have finally found us here along the central California coast, my attention focuses on finding weather windows for walks in the wild. During a gentle shower, or a just after a stormy squall, the forests and fields are freshened and it’s a fine time to take to the trail.

Check out these and other hikes Jules has taken on this Google map.

I. Arroyo Hondo, January 18, 2012, after months of drought-like conditions

We only a have an hour or two before dark and dinner in Bolinas, so a few friends and I decide to take a short walk. Although not an official designated trail, this fire road at the southern end of the Park, the trail we take begins at the end of Mesa Road, in the parking lot of the Point Reyes Bird Observatory’s Palomarin Field Station.

With me are some friends. We are acquainted through circuitous routes, but Jack Nisbet, Gene Hunn and I have each worked at “Palo” banding landbirds at some point in our lives, so PRBO’s Field Station seems a natural place to start the hike. Jack has written extensively on the human and natural history of the Pacific northwest and his recent book, The Collector (2009), recounts the remarkable career of David Douglas–for whom our esteemed Douglas-fir is named–in his botanical collecting trips throughout the Pacific Northwest.

From the field station’s parking lot, a narrow trail leads along the marine terrace, then drops down into the arroyo and crosses a wooden footbridge. The arroyo is deeply incised here and the steep canyon walls host a fern grotto–mostly maidenhair, bracken and sword ferns, with a few polypody mixed in.

At the top of the south bank, a large buckeye (Aesculus californica) is leaning precariously toward the arroyo; its lower trunk is swollen with odd bulbous goiters that we ponder over. Huge galls? Disease? Only later, after querying some botanist friends do we come to understand that the growths are probably advantageous root burls, incipient “prop roots,” developing to support the tree should the bank erode further. This is a common condition of redwoods and bays, but none of us have noticed it in buckeyes before.

The trail passes through a small remnant patch of northern coastal scrub, then wends up to Mesa Road, which we cross and pick up the fire road that leads up Arroyo Hondo. The fire road parallels the perennial watercourse known as Arroyo Hondo Creek. (This is an oddly contradictory name because this is a perennial creek and “arroyo” means a gulch that is usually dry except after heavy rains.) There are a few small reservoirs along the creek, one of the primary sources of drinking water for the town of Bolinas.

It’s late in the day, starting to drizzle slightly, and the forest is silent accept for the distant whisper of the creek and the fir needles overhead. Although is has hardly rained this winter, the creek is still flowing modestly, fog moisture retained and released ever so reluctantly through the firs and sedimentary soils overlaying the granite bones of Inverness Ridge. The only bird sound is the occasional sibilant chitchat of chickadees and kinglets moving through the firs, or the throaty “chuck” of a hermit thrush. But we are immersed in our own chatter and may have missed some subtler sounds. We pause at the small reservoirs and look for salamanders and newts, but see only fish fingerlings, perhaps stickleback? Steelhead? The water is too clouded to tell.

After about a mile the fire road comes to an end; we thought it might connect to the Ridge Trail, so we start to follow an overgrown game trail into the brambles, but get only a few feet before blackberry vines and fear of poison oak convince us otherwise. Jack, the intrepid explorer (like David Douglas), continues ahead and we decide to wait for his evaluation. A winter wren is scolding us from the understory tangle and we crane our necks for a better view. Then Jack returns, having discovered the trail impassable, but he is carrying a beautiful scarlet elf cup fungus, an unexpected find.

Dusk is deepening. As we walk back to the car parked on Mesa Road, we discuss earlier walks up this same trail, walks each of us have taken separately, each in decades past. We all remember hearing or seeing a northern spotted owl in this forest, that spirit of the old growth, an early encounter that etched itself into our individual and collective memories. Near the entry gate we find a small owl pellet in the road, rounded and about the size of a strawberry. I tease the charcoal hair apart and find the jawbone of a mammal, maybe a shrew mole. The pellet seems too small for a spotted owl, and we speculate that is was cast by either the smaller saw-whet or screech owl, but come to no conclusion, just another question to linger as we head back to Mary and Tim’s house for dinner. It seems it’s always the unexpected that one encounters on these hikes, and those are the memories one takes home–a scarlet fungus, buckeye burls, an unidentified owl pellet.

II. Woodpecker Trail, January 21, 2012, after some much needed, quenching rain.

Another short, easy hike (0.7 miles; 30 minutes unless you stop to photograph mushrooms), the Woodpecker Trail branches off from the beginning of the Bear Valley trailhead near Park Headquarters.

-

American Robin on the Bear Valley Trailhead sign, where the Woodpecker Trail begins. Photo by Jules Evens.

A perfect winter stroll between storm fronts, the dirt path climbs gently into a small stand of fir and tanoak, across an open field, then into the deeper forest. As it enters the mixed evergreen forest, dominated by Douglas-fir, but shared with burly old bays and senescent tanoaks (dying from sudden oak death syndrome), the trail parallels Sky Creek, a narrow and deeply incised true arroyo.

The moisture of the recent (and reticent) rain has wakened the treefrogs (aka Pacific Chorus Frog, Pseudacris sierra), and any winter walk through the freshly christened forest is accompanied by the reassuring croaks of this little sprite. Perhaps the most abundant amphibian on the Pacific coast, treefrogs are only an inch or two long and females are slightly larger than males. (This size disparity, a condition called “reverse dimorphism,” was undoubtedly coined by a man.) During the breeding season (January-April), males can be distinguished from females by the red blush on the wrinkly throat; the female’s throat is smooth and creamy white. The dorsal coloration is highly variable; many are bright electric green, but some range from rusty to brown, often mottled, and the color can fade or brighten to blend with the background, chameleon-like. Treefrogs wear a bandit mask, a black stripe reaching from the nostril, through the eye to the shoulder.

After these first rains, tree frogs gather is ponds and puddles, calm back-eddies and small basins, the frog symphony strikes up–a signature winter sound of the peninsula. Listen here.

-

Pacific chorus frog. Photo © Gary Nafis, californiaherps.com. Used under Creative Commons for nonprofit use, as described here.

The shady forest floor is thick with windfall–branches and twigs, broken tree trunks, a verdant cover of sword fern above a thick carpet of tan oak leaves. The decaying tree trunks support their own communities–mosses, lichens, liverworts, and fungal associations.

-

A single frond of a polypody fern points to clusters of (what I believe are) sulphur tufts (Naematoloma fasciculare) sprouting at the base of a California bay burl. Photo by Jules Evens.

I’m no mycologist, but the fruiting bodies of a fetching cluster of fungi sprouting from a mossy bed catches my eye. In Audubon’s “Field Guide to Mushrooms” I find a seemingly similar image in a section of “small, fragile, gilled mushrooms” that identifies them as “Sulphur Tufts,” a name that captures both the subtlety of the colors and their delicate structure. (Although perhaps descriptive, not all mushroom names are quite so comely–“dead man’s fingers,” “cleft-foot deathcap,” and the tumid “stinkhorns” of the genus Phallus.)

Nearby a scarlet glimmer beneath a sword fern signals another secret treasure, another cluster of “small, fragile gilled mushrooms,” in a triplet row. Again, I flip through the pictures in the field guide and decide on the waxycups (Hygrocybe), uncertain of the species but probably the Vermillion Waxycap (H. coccinea). The text says, “Edible, but not worth the effort.” Really, the thought never crossed my mind.

-

A trio of vermilion waxycaps (Hygrocybe coccinea) hidden beneath a canopy of sword ferns. Photo by Jules Evens.

Further up the trail I encounter an older couple. We stop to greet one another and agree on the loveliness of the day. As the woman points to yet another surprise–a most unmushroom-like mushroom, delicate tendrils reaching up from the leaf litter–I notice her British accent. Based on only the most cursory characteristics, I identify it as “white coral fungus.” She nods in agreement, but says, diplomatically, “we have different names for them in England.”

-

White coral fungus (Ramariopsis kunzei), rather common along the side of the Woodpecker Trail, this damp Monday afternoon. Photo by Jules Evens.

Completing the Woodpecker Trail loop, I emerge from the forest near the Morgan Horse Farm and walk back to the parking lot through open grassland. A pair of Western Bluebirds sallies out from the fencerow, capturing insects from the ground. The fence that surrounds the horse pastures and Park Headquarters is a most reliable place to see bluebirds in any season. In winter they are often accompanied by several Yellow-rumped (“Audubon’s”) Warblers, as they are today. These forest-nesting warblers, adapted more to leaf gleaning than fly-catching, seem to rely on the larger-eyed bluebirds for finding insects when foraging out in the open grasses.

Although this walk was short, and although I’ve been hiking these trails for more than three decades, I had come upon several species I’d never seen (or noticed) before. Whether this was of my lack of attentiveness in the past, the rarity of these fungi, or the novelty of late rains, I’m not sure. But I do know that little miracles appeared along this well-trod trail. It seems that every time we go out on the trail we notice things we’ve never seen before, or see things in a different stage of its life cycle, or in a different light . . . or maybe with different eyes.

Seeing these inconspicuous mushrooms and wondering over their role in the forest reminds me of a passage from my book, The Natural History of the Point Reyes Peninsula (2008, UC Press).

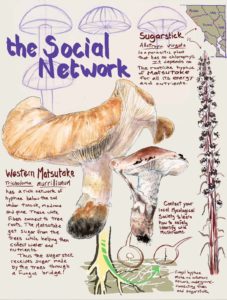

There is a vast conspiracy beneath the soil’s surface of which most of us are only dimly aware. These co-conspirators are fungi and plant roots. The subterranean fungi–as distinct from the above ground fruiting bodies we call mushrooms–provision mineral nutrients (phosphorous, nitrogen, etc.) from the soil to the roots of the plants. In exchange, the plants feed their fungal partners sugars they have photosynthesized above ground. This symbiotic relationship produces a complex network of energy pathways known as mychrorhizae.

Within this vast conspiracy–that literally runs the world–there is an obvious metaphor. The underlying impulse of the oldest beings on earth is collaboration, mutualism, symbiosis. I wasn’t the first human being to recognize the cooperative impulses of the non-human world:

In trees and plants, one may trace the vestiges of amity and love . . .The vine embraces the elm, and other plants cling to the vine. So that things which have no powers of sense to perceive anything else, seem strongly to feel the advantages of union. –Desiderius Erasmus (1465-1536)