Flowering bear grass is not a common sight in the Bay Area. But in 2018, it was plentiful in the pygmy forest at Bouverie Preserve in Sonoma County. With a puff of dense, white flowers sitting atop a long stalk and wiry olive leaves falling outward from the base, it is an ephemeral, tender sight. Bear grass, like the redwood lily and Napa false indigo, is a rare understory annual that can grow after dead, dense forest floor debris has been cleared by fire, earning it the moniker of “fire follower.” As larger shrubs start closing in though, it disappears again until the next fire.

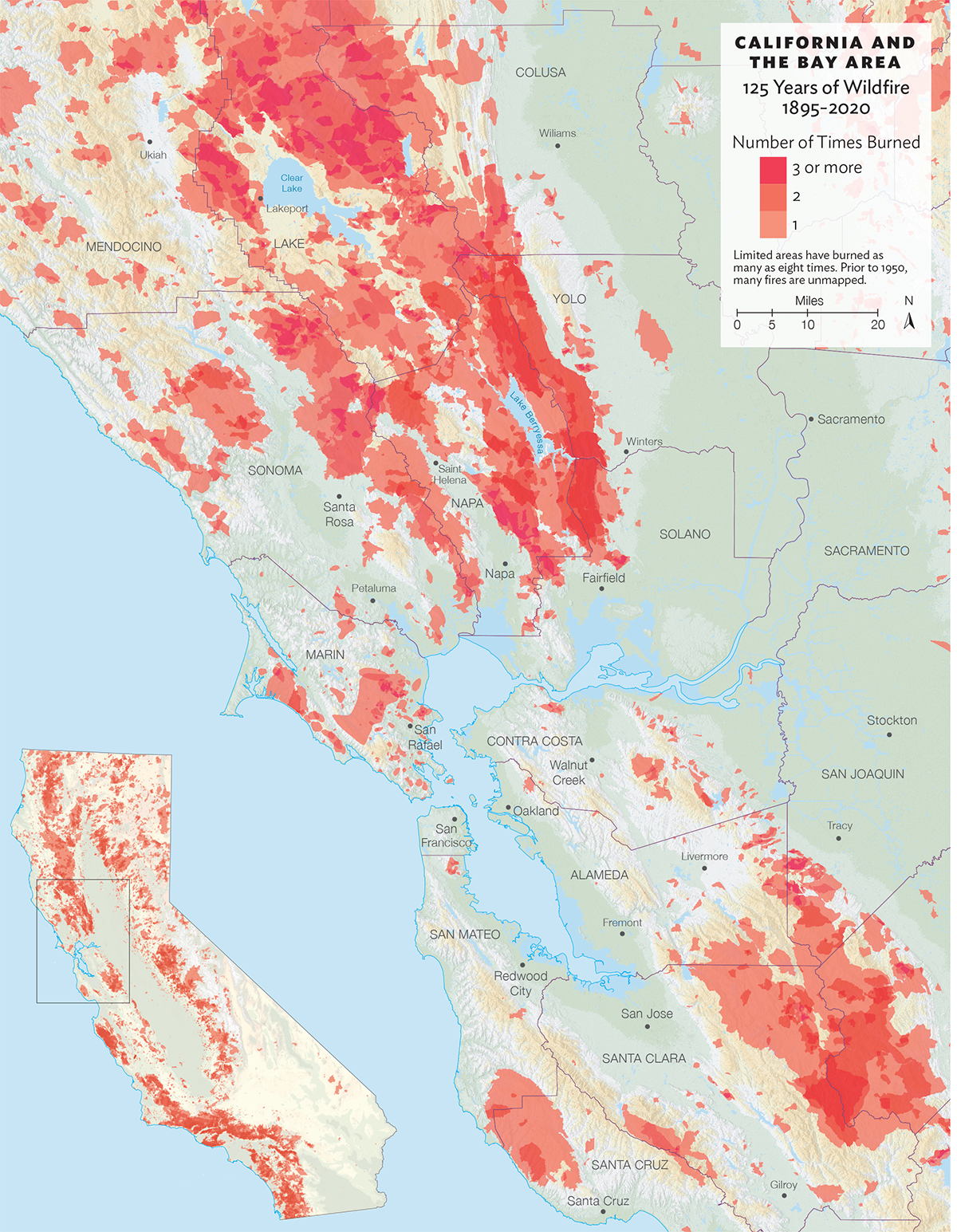

Almost four years ago, more than 75 percent of the 535-acre preserve, adjacent to Glen Ellen, burned during the Nuns Fire. In total, the Central LNU Complex conflagration, an amalgam of six fires including Nuns, devastated a total of some 56,500 acres in Napa and Sonoma counties, killing two people and destroying 1,527 structures. Those fires also foreshadowed the wildfire seasons to come—in 2020 five of the six largest fires in California’s modern history burned simultaneously. The cost alone could tell the story: The average annual expenditure of the fire suppression emergency fund of the Forestry and Fire Protection Department (Cal Fire) in 1980-81 was about $21 million. In 1990-91 this had increased to around $70 million; in 2000-01 to $114 million. By 2020-21 the cost was estimated at close to $1 billion. More than a century of fire suppression and a changing climate have increased both the size and intensity of wildfires in the state, and there is no longer a “no fire” option here.

Still, bear grass and other flora like it are a testament to fire’s centrality in these spaces, something we are beginning to acknowledge again. In January, California released its Wildfire and Forest Resilience Action Plan, which includes proactive burning and thinning of vegetation over the next four years, of up to 100,000 acres by Cal Fire and up to 500,000 acres by the U.S. Forest Service. In April, Governor Gavin Newsom announced a legislative package of $536 million to get an early start on reducing fire risk. A month later, he proposed an additional $2 billion in disaster preparedness, focused on fire. “I’ve definitely noticed a huge shift in the last five years,” says Sasha Berleman, a fire ecologist who works with the Bouverie Preserve. “That’s being, in its core, driven by how frequently we’re experiencing catastrophic fire now.”

Wildfire has abruptly become a part of California’s summer and fall, staking out a new definition of normal for almost 40 million people. As the state and communities scramble to adapt—through massive investment and a torrent of legislation, insurance reform and fireproofing homes—the concept of “learning to live with fire” has become pervasive. Baked into that often-used phrase are many more intentionally set fires that aim to reduce the risk of catastrophic wildfire. While everyone wants less wildfire risk, what will an increase in controlled fires mean to the landscapes, wildlife, air, and water around us? Who will set and manage the fires and how frequently will they occur? What will it mean to really live with fire?

Over half of California’s ecosystems are fire dependent, so they need fire to persist. Prescribed fires are planned and controlled fires set during favorable weather in fire-adapted ecosystems to reduce their flammable, dead plant matter, induce certain flora to grow, and control disease or pests in the landscape, among other goals. On average, California burns around 125,000 acres of land a year, according to the California Air Resources Board. Florida burns around 2 million acres, and California is almost 2.5 times the size of Florida.

Prescribed fires, in conjunction with mechanically thinning a forest’s understory and grazing on grasslands and shrubs where appropriate, can reduce the intensity of a wildfire when it burns through these treated areas. But using prescribed fire as a tool for landscape management is still nascent in the Bay Area. Berleman is among those ushering in an era of good fire as director of Fire Forward, a program run by the environmental nonprofit Audubon Canyon Ranch in the North Bay, of which Bouverie Preserve is a part. “Very targeted, ecologically minded, prescribed burning is a valuable part of the solution,” Berleman says.

If 100,000 acres of prescribed fire and thinning sounds like a lot, it’s not. Prior to European settlement, fire was common and constant in California. Estimates suggest that roughly between 4.5 and 12 million acres burned annually in California pre-1800. Lightning ignited many of the fires, but so did Indigenous tribes, whose practices possibly burned 2 million acres a year. The land was burned in rotation, areas sometimes measuring as small as a tenth or quarter of an acre.

“The fire regime in the greater Bay Area counties was dominated by Indigenous burning,” says UC Berkeley professor Scott Stephens, one of the foremost fire experts in California. “There’s been much more change in these ecosystems than people realize through the reduction of anthropogenic burning for probably, easily, over two centuries.” Indigenous communities throughout California continue to burn the land as their ancestors did, albeit on a smaller scale, for food, medicine, and basket-weaving material; for ceremony; to protect human communities; and other reasons. Many Indigenous weavers use bear grass in baskets, hats, and dresses.

How will burning tens of thousands of acres in California help reduce the threat of catastrophic wildfire? It’s true that it removes dead wood and other vegetation that fuel wildfire, but it can and often does a lot more than that. Fire is a sophisticated tool that can reorganize a landscape in a multitude of ways, including which species live there and demands on water. When a fire expert like Berleman lights a controlled burn, she is weighing an array of public goals: a community’s safety from destructive wildfires, whether a habitat is adapted to fire, what might help the habitat survive climate change and drought, biodiversity, aesthetics, and smoke pollution, among other concerns.

Take oak woodlands, for example. These woodlands are one of the most biodiverse habitats in the West. And in the nine-county Bay Area, vegetation classes that include oaks span more than 900,000 acres, according to the Conservation Lands Network. Healthy oak woodlands need fire every three to 15 years to thrive. When fire is removed as a source of disturbance from an oak-dominated ecosystem, trees like Douglas fir, bay laurel, and madrone can quickly overtake the woodland species. “In the absence of that stewardship—using prescribed burning and a low-intensity fire in the understory—they become encroached [on] and in some cases completely converted to other systems,” Berleman says.

There are myriad reasons fire ecologists want to preserve these woodlands—they provide food for humans and animals, encourage the growth of a diversity of grasses and wildflowers in their understory, and make good shelters for birds and small animals. They are also an important source for acorns, still used by Indigenous communities to grind into acorn meal. Many oak woodlands are old-growth forests, with even small oaks being hundreds of years old. When managed and kept in a more open condition, they can also become anchor points—spaces accessible to fire crews—to protect our homes. “They are more resilient to climate change than encroaching conifer forests are,” says Lenya Quinn-Davidson, area fire adviser for Humboldt County and director of the Northern California Prescribed Fire Council. “Oak woodlands also use less water than a dense, encroaching forest does.”

Fire scientists continue to try to understand how Bay Area and California ecosystems have changed due to fire suppression, and encroachment repeatedly turns up in their findings. Previously, “we didn’t have all of this continuous canopy cover that is just literally from Napa County to Lake County to Santa Cruz County, where most of these areas have grown to the point where we have very little light gaps on the ground,” Stephens says. “These systems used to be so much more open.”

Just how open is a question of inference, however. In 1911, large areas of the predominantly mixed conifer forests in the central Sierra Nevada were inventoried by the Forest Service. That information gives researchers an almost accurate measure of what the forest looked like just after fire suppression began. Forest managers can compare these historical plot networks to areas that have recently been damaged by wildfire or disease. Having a clear picture of what a managed forest plot looked like in the past is in some ways a road map for the future.

But the forests of the central Sierra Nevada aren’t the redwood, oak woodland, and chaparral habitats of the Bay Area. “There’s nothing like that in coastal California. So it’s a harder place to get those numbers. We just don’t have a comparable data set,” Stephens says about the 1911 inventories. “But I think the tribes themselves become an incredible resource if they choose to work with us.”

In the Santa Cruz Mountains, Stephens is collaborating with the Amah Mutsun Tribal Band to restore an oak woodland that the Amah Mutsun use for acorn production.

In the North Bay, Berleman has been leading and learning from prescribed burns for years. She has focused on mixed evergreen, mixed conifer, woodlands, coastal prairie, and grasslands—habitats in which prescribed burns can strategically reduce the intensity of future wildfires. In June 2019, almost two years after the Nuns Fire, she and a cooperative volunteer team burned 21 acres of grassland at Bouverie, reducing wildfire hazards from the annual buildup along Highway 12 and under power lines. But the fire also removed invasive weeds that crowd out native wildflowers and bunchgrasses in the process.

Later that month, in the Mayacamas Mountains of Sonoma, Berleman led a six-acre prescribed burn that reduced Douglas fir and tanoaks in the mixed evergreen forest and woodland understory. In October, at the Martin Griffin Preserve in West Marin, the team burned 9.5 acres of thinned Douglas firs that had been encroaching on the coastal prairie for over 30 years. Prairie needs to burn at short fire intervals, about every five years and with fires of high intensity, for these desired impacts to occur.

The grasslands burn at Bouverie ensured that in the spring of 2020, the meadows were filled with native blooms of lupine, Sonoma sunshine, and meadowfoam. In a future that is influenced by climate change and bigger wildfires, Berleman isn’t necessarily trying to return to something that was historically there. Fire Forward is looking at what these ecosystems need to persist for the long haul.

A part of that resilience will come from these areas being better prepared for drought, disease, and wildfires. Forests of pine, fir, and cedar in the central and southern Sierra Nevada that have been burned in recent decades with semi-frequent prescribed fire are more resilient to drought, because fewer, healthier trees can access the scarce resources. Forests of drought-stressed trees contribute to catastrophic wildfires. A research project called Silent Straws, led by Quinn-Davidson, is exploring how much excess water is utilized by the forest that grew because of fire suppression. In land areas being studied, some springs that have been running for centuries have dried up. Quinn-Davidson believes it is because they are now surrounded by forested areas that weren’t previously forests. “If you picture a more fire-adapted landscape, fire actually increases these [water] flows. If you have more frequent fire, you’re going to have more water available to flow in the streams and creeks,” she says.

As California braces for drought, with two years of below-average rainfall, systematic management of basins that contain mixed evergreen forests and oak woodlands in the Bay Area becomes urgent. Governor Newsom officially declared a drought emergency in 41 counties, six of which are in the Bay Area. In Marin’s reservoirs, water levels are currently at about 50 percent, the lowest in 40 years. Berleman hopes to see some springs pop up there this year. With more three-to-five-day burn events planned that would carry fire through contiguous acres of major project areas in Sonoma and Marin, the likelihood of water later reappearing on the landscape is high.

“You really have to be driven by what you are managing for,” Quinn-Davidson says. “How can we use fuel treatments and prescribed fire to set the landscape and our communities up for success?”

The trickier part is maintenance. Reintroducing prescribed fire into Bay Area ecosystems will require tending to those areas in perpetuity. The more acres burned, the more monitoring and maintenance they will need. “You are going to have to keep this stewardship up. If you go in there and treat it and feel like somehow you’re finished, and you’ve been successful, unfortunately, that’s not the case,” Stephens says. “You’ve got to continue this conversation with the land that goes forever.” Success will require local burns by the people living in those areas. This is where prescribed burn associations (PBAs) like the Good Fire Alliance—which started in 2018 and is the Bay Area’s first such entity—and community wildfire protection plans (CWPP) take center stage. PBAs are networks within communities that help private landowners introduce prescribed fire onto their land. There are currently 14 such associations in California. CWPPs are county-level, or even smaller, plans that come up with a strategy for fire use; these prioritize strategic areas and may include specific projects. Together the efforts lay the groundwork for expanding prescribed burns over large areas.

In Occidental in Sonoma County, neighbors are coming together to look at each other’s properties and helping to conduct small prescribed burns for understory cleaning. With that process comes a sense of ownership beyond their land, and this feeling of community helps promote wildfire preparedness. “We’re basically copying the southeast U.S. [Florida, Georgia, Alabama]—that’s the prescribed burn capital of the United States. Seventy-five percent of the prescribed fire that happens every year is on private ground by private people,” Stephens says. One vision for the future could include neighborhoods working together with a shared resource pool and learning to burn in the winter during low-fire-risk windows.

As climate change exacerbates drought and increases the likelihood of more catastrophic wildfires, such windows of opportunity will become more and more important. One impact of climate change that could be advantageous, though, is the increasing intermittent winter rainfall, giving rise to low-risk burning opportunities. “If every landowner was partnered with the community and knew how to safely and diligently put down the prescribed burn using a drip torch and a backpack pump in between each of those rainstorms, and committed to that relationship with the land, I think we could easily reach 100,000 acres of good healthy fire on the ground through winter,” Berleman says. “It is just going to take that cultural shift and knowledge building at the local and regional scale.”

Doing this work at scale could have air quality impacts, because ideal conditions for burning tend to align across swaths of Northern California. But Stephens, Berleman, and many others studying fire argue that air quality problems could be minimized through planning. “If we do what we talked about, where we’re burning, and often, and working with tribes, smoke will be a part of the environment,” Stephens says. “You go to the South in the late spring, there’s smoke everywhere. People just say, ‘Yes, they are burning the rough—they keep the fire hazard down. It’s something we’re going to deal with.’” And while it might be a chronic situation, burning under the right conditions allows smoke to lift and disperse, causing minimal impact to people on the ground. Wildfire smoke, on the other hand, can be extremely toxic and harmful to the health of people even hundreds of miles away.

Wildfires are part of California’s legacy and will continue to be so. If prescribed fire can reduce the density of tree cover, understory crowding, and vegetation within the greater Bay Area, then when wildfires do ignite, they will be more manageable and easily suppressed by firefighters. “What a note of optimism for our future, right?” Quinn-Davidson suggests. “Because there’s something we can do. If we really get busy and address these problems, we have a chance of overwhelming the effects of climate change.”

Then, maybe every few years, the bear grass will greet us by pushing up through the scorched earth—a delicate beacon of fire’s rightful path through our lands.