Text and research by Bay Nature staff.

This fall is one to look for change. During what will hopefully be the last dry months of the driest two-year stretch in recorded California history, how are species responding? What do you see and not see? How does it compare to the past?

All Together Now

When a tree like a coast live oak (Quercus agrifolia) bears a bumper crop of acorns in fall, it synchronizes with all the other coast live oaks also bearing an inordinate number of acorns. How? You can’t miss it when it happens—there are acorns everywhere. This age-old question about masting — when a plant species coordinates with others of its kind to produce a huge seed crop during seemingly random years—remains a difficult nut to crack (#badpun). But we do know that coast live oaks largely mast in unison up and down the state. How frequently is more complicated. “There have been two VERY good years — 1992 and 2017 — and several pretty good years: 2000 and 2010, maybe 2019,” says Walter Koenig, a preeminent scholar of California’s oak masting, with four decades of data. “Whether you want to say that this means there’s a ‘mast’ year only once every 20 years or so or rather more often is, I fear, pretty much a matter of taste.”

Measuring Change

The mid-September return of ruby-crowned kinglets (Regulus calendula) to the Bay Area from their breeding grounds up north used to be a reliable sign that fall was about to begin. But what was once regular as clockwork is now shifting. Over the last 35 years these tiny birds have shown up progressively earlier — at this point sooner by almost a week, according to data collected in Point Reyes National Seashore by Point Blue Conservation Science. The warming climate’s cascade of changes includes an earlier onset of spring, which can lead to an earlier breeding season and earlier insect proliferation, factors that may explain the kinglet’s new calendar.

Seeing Things

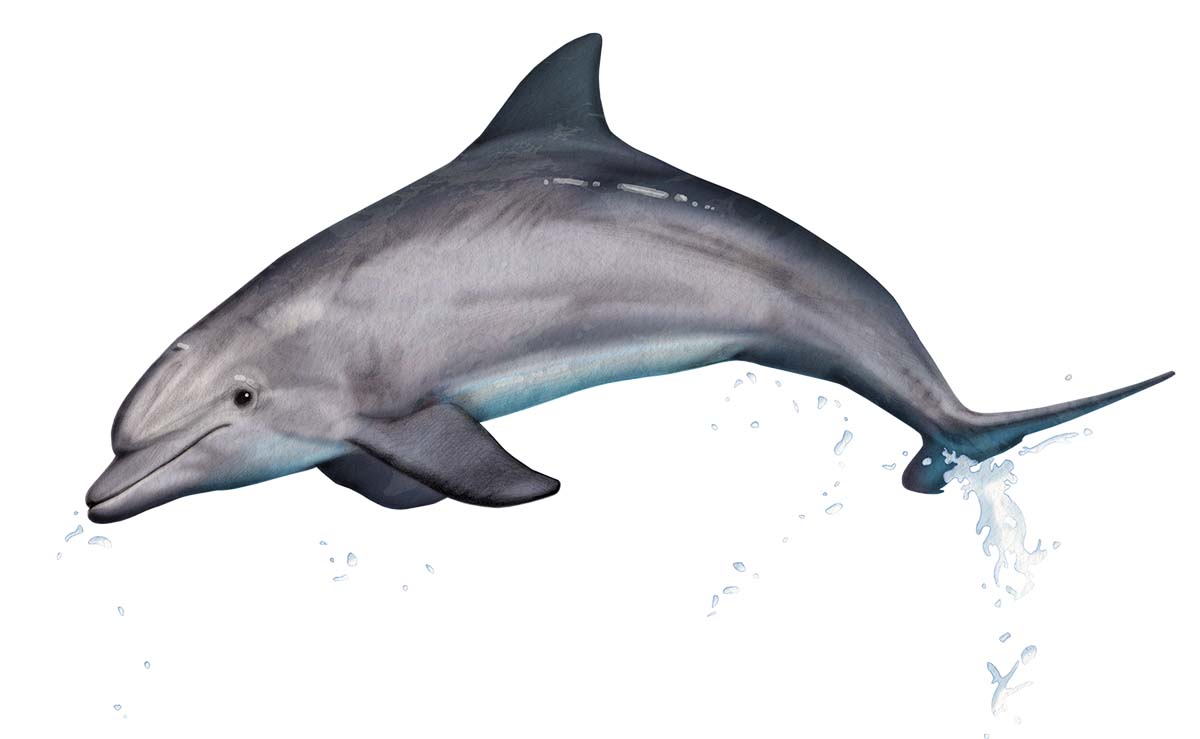

You’re not mistaken: you did see a dolphin in San Francisco Bay. Bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) have been entering the Bay for at least a decade, says Bill Keener of The Marine Mammal Center. An estimated 323 of them live along California’s coast, and they’re often seen during summer and fall from Ocean Beach or Lands End and Sutro Baths, or even Fort Point. Now they sporadically enter the Bay and Keener tracks every one of them. You might spot them speeding to pursue prey or resting. Look for their hooked dorsal fin and bottle-like beak, and report your sightings to The Marine Mammal Center.

Wolf’s Milk

Do you know what a slime mold is? If not, prepare yourself. Slime molds are part animal, part fungi. Kind of. And you can see a fairly common species, known as wolf’s milk (Lycogala epidendrum), on rotting logs in the Bay Area, particularly during fall. Or at least you can see the round pink to black fruiting bodies that release spores for reproduction (the fungi part). You’re less likely to see wolf’s milk’s younger form, when it is a single cell with multiple nuclei, creeping over wood, amoeba-like, eating detritus and bacteria as it goes (the animal part). The Syfy channel needs to get on this. But until they do, if you encounter a coral to reddish-colored mass called a plasmodium on rotting vegetation, it might be prepubescent wolf’s milk!

Virus Blues

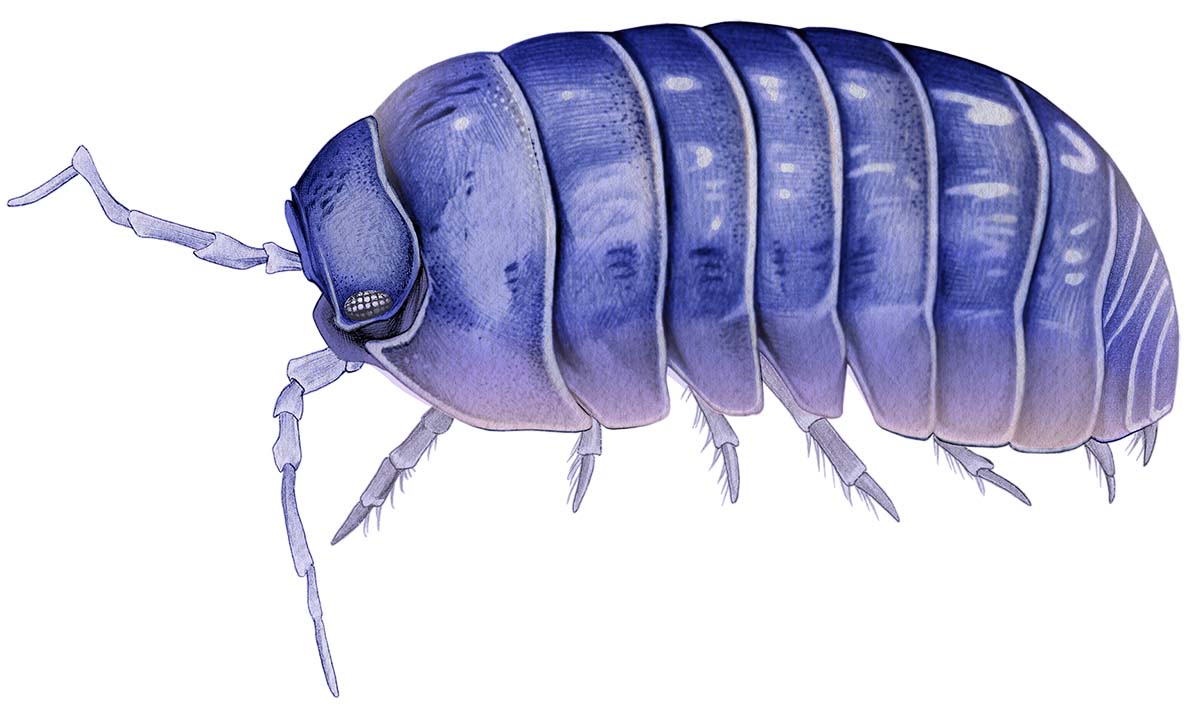

Have you ever seen an indigo-colored pill bug? It’s not a variety of roly poly, as was once believed. It’s a pill bug infected with the virus species IIV-31 (invertebrate iridescent virus-31), a 20-sided virion that accumulates in the pill bug’s tissues, creating a colorful iridescent effect. The virus can also cause the pill bug to become increasingly unresponsive and die. There’s still a lot to learn about IIV-31—although it may be as old as the Early Cretaceous—so researchers have taken to iNaturalist, among other citizen science websites, reviewing incidence of this virus worldwide. If you encounter a blue pill bug, help science by uploading and tagging your photo with the virus species on iNaturalist.

Big Bird

New to birding? Here’s a fall shore species to watch for any place along the coast or the Bay’s shoreline or amid agricultural fields in the Central Valley: the long-billed curlew (Numenius americanus). The largest shorebird we’ve (and North America’s) got, and with a hooked beak arcing like a crescent moon, it’s easy to identify. The beak tip, packed with nerve receptors, senses movement as it probes the mud for crayfish, crabs, and clams, among other delicacies. That same adaptation helps these curlews hunt in grasslands, where they breed in spring. Curlews begin arriving in the Bay Area in early summer and stay through March, although a few hang around all year (and are suspected to be juveniles still growing out their bills).