It can take time for new ways of thinking to penetrate institutions. But the ideas driving the environmental and social movements of the early 1970s gained a strong foothold in the East Bay Regional Park District, thanks in large part to a cohort of young park workers hired during that decade. These workers, many of them still college students, had come of age during the era of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring and the first Earth Day, as well as the anti-war movement and the civil and women’s rights movements. Before long, these workers’ influence in the district was felt in everything from where fences were built to which species thrived and what land was saved. Over the past 40 years, this generation has grown up in and with the East Bay parks and built a regional park district that is the largest in the nation, with some 115,000 acres of parkland and trails in 65 units.

The environmental movement was a growing force in the Bay Area of the 1970s. Protection of undeveloped lands was a popular cause, and in 1971 the state Legislature allowed the district to increase taxes to finance the purchase of new parkland. Time was of the essence as environmental groups and the park district faced off against developers competing for the “best of the last” farmland and shoreline parcels flanking the Bay’s urban core. Boosted by the new funds, the district more than doubled in size between 1968 and 1984.

EXPLORING THE EAST BAY REGIONAL PARKS

This story is part of a series exploring the natural and cultural history of the East Bay Regional Park District (EBRPD), which is celebrating its 80th anniversary. The series is sponsored by the district, which manages 114,000 acres of public open space in Alameda and Contra Costa counties.

To accommodate that growth, the district took on scores of college kids as summer “groundsmen,” the early term for ranger. These young workers removed old infrastructure, debris, junk, and invasive species in an effort to restore newly purchased parcels to a more natural state. In an era when procedures had not yet been standardized, the new staffers were often able to follow their own ideas: When a park needed a new trail, a staff member came up with a plan and built it.

Now, those young workers have started to retire, and with them go four decades of history and insights into the landscapes they tended and, in many cases, saved. We asked six park workers hired in the 1970s and early 1980s to share some tales of their years with the district.

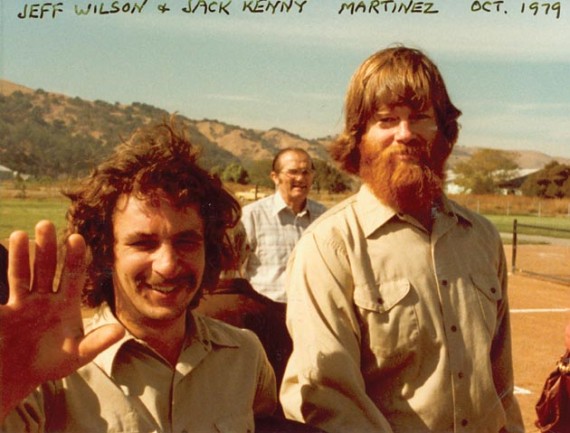

Jeff Wilson

HIRED 1974 / RETIRED 2012

For all of Jeff Wilson’s accomplishments, management positions held, and years worked in the park district, he lights up most while recounting his early days as a groundsman at Black Diamond Mines, a regional preserve northeast of Mount Diablo. “When you worked in the outlying parks in those days, you might as well have been in Siberia,” he recalls. “Communication was so different then. Every few days we’d get an envelope full of memos.”

The working conditions were different, too. Wilson’s first office was a plywood shed. Mornings began with running a stick under the furniture to flush out the rattlesnakes. “I got real smart about rattlesnakes real fast,” he says. Although he grew up a backpacker, turning out snakes at work wasn’t exactly old hat for this educated hippie from Berkeley who was part of the new wave of college graduates the park district was hiring. As the acreage of parklands ballooned in the 1970s, then-Superintendent of Parks Robert Blau saw a need to take on young people with the skills to do both manual labor and office jobs that required reading, writing, and a sensibility that could connect with the urban Bay Area population. Two years after he was hired in 1974, Wilson started working to get Black Diamond’s 3,000 acres of diverse terrain and vegetation, dotted with former town sites and defunct coal and sand mines, in shape to be opened to the public.

Wilson’s boss at Black Diamond was part of the old guard, a bonafide Portuguese cowboy who didn’t think much of uppity urbanites. But Wilson was lucky; being half Portuguese helped him earn the boss’s trust as he learned the trade. It was an era of minimal resources and the ethos was make do and figure it out. “Art students are really good at that,” says Wilson, who had earned a bfa in sculpture from the California College of Arts and Crafts. “So I succeeded in staying alive and not really embarrassing myself too much.”

His first assignment was to haul away a scrapyard’s worth of abandoned cars and junk. Then he built fences in places no one would notice, so that visitors could have a more natural experience. And he worked on building the trails that people still hike on today. “It was a different world back then,” he says. “Seeing what you did all those years ago being used now is really something.”

At the same time, Wilson started to study botany, took biology classes, joined the California Native Plant Society, and expanded his knowledge of birds. He helped compile some of the first species lists for Black Diamond.

Just as Blau had anticipated decades before, Wilson and many from his generation moved from work in the field into management. Wilson left Black Diamond to work at Briones Regional Park, where he lived and raised his kids in a park residence for 18 years. He advanced to supervisor of Tilden Park, staying at the job for 15 years, longer than anyone else has held the position. Heading up such a heavily used park meant learning lessons in public relations and politics. He also mentored many new rangers and saw five of his staff reach supervisory positions themselves, and he helped others find money for their projects. He then put all those skills and more to use as the district’s wildlands unit manager, overseeing all the large open space parks before being promoted to chief of park operations in 2010. He retired two years later, in 2012.

“I stayed at the park district for so long in part because it was like a big family,” Wilson says. “In the end, it was more about people than parks.”

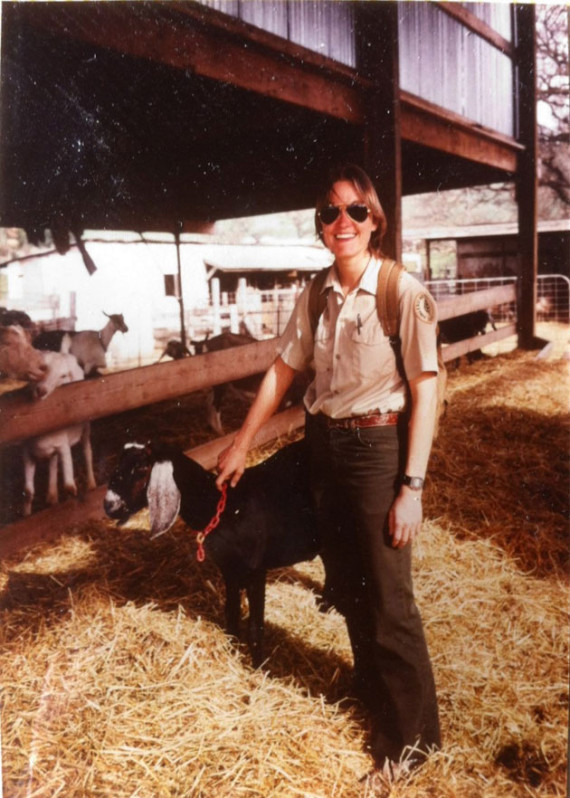

Anne Scheer

HIRED 1974 / RETIRED 2014

Just two years after Anne Scheer began a summer job lifeguarding alongside other UC Berkeley students at Lake Anza in Tilden Regional Park, she found herself holding a chain saw and cutting down enormous eucalyptus trees in the park. “I grew up in east Oakland. I didn’t know anything about tools,” she says, laughing. In retrospect, it was the inaugural step of a long career in demolition and building—literally and figuratively.

In 1972, an 11-day run of freezing temperatures killed or damaged thousands of eucalyptus trees in the ridgeline parks from Tilden to Chabot. Their dead wood and highly flammable sap posed a tremendous fire hazard, so the district received emergency funds to launch an all-out effort to clear the dead trees and create a firebreak. Scheer and many other young park employees were drafted into the project. She ended up in a crew of guys amenable to teaching her the precarious art of felling 100-foot-tall trees.

The eucalyptus freeze also brought up the issue of pesticides. To make sure that the damaged trees didn’t resprout, park staff applied the harsh herbicide 2,4-d, a component of Agent Orange. This was in the early days of pesticide regulation, and workers were applying the herbicide with minimal protection or training. So the union fought to create a district-wide advisory ecology committee and a permanent position devoted to integrated pest management. The committee still exists today and tracks all pesticide use in the district and investigates more benign alternatives. Scheer served on the committee until her retirement.

Five years after the freeze, Scheer’s long-standing interest in architecture and “how things work” landed her in the district’s maintenance department, which handles plumbing, roads, roofing, trails, and much more. Eventually, in 2003, she became the first female chief of the department. “I can’t remember what I did yesterday,” Scheer jokes, “but I can remember where the septic line to the merry-go-round is. I could get a shovel, dig down, and hit it.”

To help her advance from being a novice with tools to overseeing major infrastructure projects, Scheer took a slew of UC Berkeley classes in subjects such as surveying, construction materials, architecture, and wood-destroying insects. She also had to have a pretty thick skin.

The park district was making strides in changing its male-dominated culture in the early 1980s, but the maintenance department wasn’t exactly leading the way. Scheer recalls a run-in with a mechanic, whom she asked on behalf of another female employee to remove the girlie pictures hanging in the office. The guys in the shop were not happy about that and the next day, a similar array of photos “mysteriously” appeared on her locker. She took them down; but the next morning they were back up. It went on like that for several days, until the guerilla decorating finally ceased. “It bothered some people a lot, but it didn’t get to me. I knew they would get tired of it before I did,” she says.

In her last years before retirement, Scheer was promoted to chief of operations, one of the top leadership positions in the district. Once again she was the first woman to hold the position, and she says guiding young park employees in the right direction is what thrilled her most. “It sounds sappy, but I love this job so much. I realize what a cool place it is to work, how many things you can do, and I just want to share that with other people,” she says. “I want somebody else to have a career as cool as mine.”

Dionisio “Dee” Rosario

HIRED 1975 / RETIRED 2013

Dee Rosario’s Redwood Creek vigil began in 1976 when he became a full-time groundsman at Redwood Regional Park. Service in the park district wasn’t an obvious choice for a competitive college wrestler who had been born in the Oakland projects, the son of Filipino immigrants. But he was the head of a household with three siblings, trying to pay his way through college, and needed to work. And when Rosario saw the serene, giant trees in Redwood Regional Park he thought, “Oh my God, this is meant to be.”

Providence may have had a hand in getting him there, but so did the sweeping changes in equal rights around the country, as well as a legal fight by women’s groups and the park employees’ union to require the district to hire more women and minorities. As a Filipino-American, Rosario says, “I’m indebted to that effort.” He repaid that “debt” by taking on leadership roles in the union throughout his career.

Rosario also gave back to the redwoods that inspired him. The old-growth trees in the area had been thoroughly logged during the Gold Rush. By the 1950s and ’60s the area had become a heavily used recreation site, with huge picnic areas, a baseball field, and drive-in campsites. By the time Rosario started with the district, it was all he and other park staff could do to clean up all the trash after busy weekends. Moreover, the natural areas of the park had become seriously degraded. Redwood Creek had been dammed to make way for a road to the camping facilities. Rosario recalls watching the native rainbow trout trying to fight their way up the muddy stream only to reach the dam and then bang their heads against it. “It was heartbreaking,” he recalls.

But in the mid-1980s, in keeping with the district’s new emphasis on natural resources, it was decided that Redwood should be restored to a more natural state. Rosario was thrilled when stonemasons constructed a fishway around the dam to the upper creek to allow the two-foot-long rainbow trout to return to their historic spawning grounds. “It was incredible,” says Rosario, “both that it got built, and that it was successful.”

When Rosario became supervisor of the park in 1996, he continued the restoration work, overseeing the elimination of picnic sites from the east side of the creek and the removal of failing footbridges. The guiding principle for all of this work was the health of Redwood Creek and its fish. “We really thought about what the fish needed—clear water, deep pools, and to be left alone during the summer,” Rosario says.

Upslope from the creek, Rosario noted that the forest understory was also in dire need of attention, so he established a small nursery to propagate redwoods and riparian species such as willows that staff planted along the recuperating creek. Invasive species were also a serious problem, but getting rid of them seemed an impossible task for the small park staff. Then, in 2002, Rosario forged a valuable partnership with well-known local TV news anchor and nearby resident Wendy Tokuda to tackle the invasive species. Together they recruited local volunteers for what has become a twice-monthly restoration event that involves roughly 3,000 hours of volunteer work annually and has dramatically reduced the presence of invasive French broom, opening up space for the return of native plants.

In Redwood Creek, the number of spawning trout has climbed to between 30 and 40 pairs. The water flows clear and the surrounding understory has slowly recovered. A few years ago, in an open area, thousands of redwood seedlings popped up. Rosario describes watching the slow rebound of the land as nothing short of spiritual. “You see how beautiful it is now and you wonder what it was like before the Gold Rush,” Rosario says. “To be part of that healing process, it makes you feel like you’ve done something worthwhile.”

Steve Edwards

HIRED 1970 / RETIRED 2013

By the time Steve Edwards was in high school in Oakland, he was already deeply involved with plants. He had grown thousands of succulents and won prizes at local fairs; his bedroom was adorned with a collection of conifer cones. Eager to find summer work at a botanic garden while he attended UC Berkeley, he went to the Regional Parks Botanic Garden in Tilden Park in search of its director, Jim Roof. Wandering the garden grounds, he approached an older man hand watering some plants and asked for Roof. The man replied, “He just left for Alaska.” Suspecting that he actually was speaking to the notoriously misanthropic Roof, Edwards persisted, explaining his passion for plants and desire for work.

His tenacity paid off. The following summer Edwards got a call from the park district offering him a job in the garden. But it came with a warning. Roof was a master botanist, historian, storyteller, and natural history writer, who founded the park’s botanic garden before World War II and then resuscitated it after it fell apart in his absence during the war. But he was also a hard man to work for, according to Edwards (and others), and the eager student lasted only two seasons in the position—long enough to help hand-build many of the rock walls found in the garden today. He spent the next few summers building trails in Las Trampas Regional Park while earning degrees in philosophy and mammalian paleontology.

Once Roof retired, Edwards returned to work in the garden and never left. “I’d wake up in the morning,” he says, reflecting on his 35 years at the garden, “and think, ‘I get to go to work today!’” In 1983 he became director of the garden and spent the next three decades furthering its mission of being a renowned and respected California native plant garden with a focus on rare species. His many field expeditions around the state contributed to the garden’s distinguished collection. One of the first was a Port Orford cedar cutting he gathered near Mount Shasta for his Ph.D. dissertation in paleobotany; the tree has since grown into a robust 70-footer. Edwards is also known for his expertise in native grassland management, geology, and human prehistory. His Saturday morning lectures on California’s natural history regularly drew more listeners than could fit in the garden’s auditorium. He published his research in peer-reviewed journals and was editor of the garden’s own well-regarded journal The Four Seasons.

He also helped foster the garden’s volunteer program and promoted a staff culture that embraced the special role of public gardens. “A lot of the people who come here live in apartments down in the city and don’t get to have their own garden—maybe two or three pots on their windowsill,” Edwards says. “All of us who work here are very aware of that. We’re providing this experience for them. Families teach their babies to walk on these lawns. We see it all the time. It’s inspiring for us. ”

Edwards recalls arguing with Roof about the role of botanic gardens and insisting that it should not be just about the plants in the ground, but also about the people who work and volunteer in it. “After 31 years as director,” Edwards says, “I’ve been able to discover the truth in what I argued theoretically back then. I’ve lived it now and realize that the more I attended to and was able to love the people I worked with, the more this place was a garden for me. We’re all growing together. We’re all tending each other.”

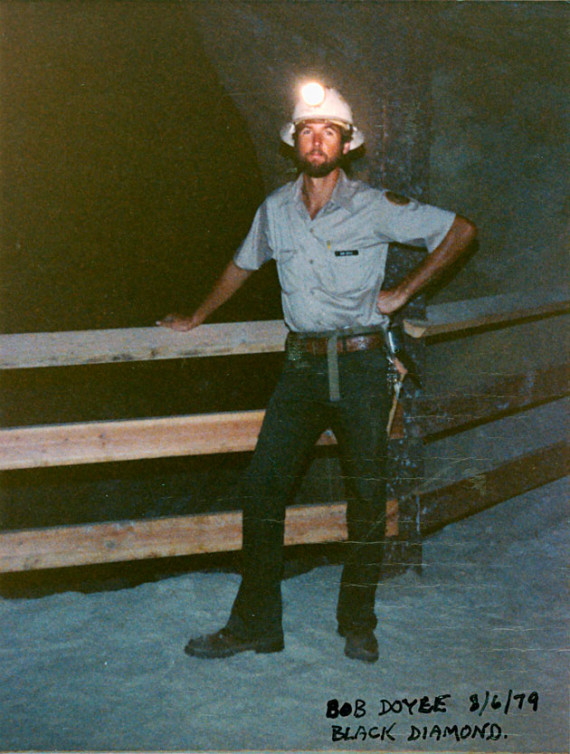

Robert Doyle

HIRED 1973 / STILL GOING

Growing up at the edge of the suburbs in Concord, Bob Doyle hung out with kids whose parents worked nearby ranches and farms. He roamed and played in their mustard fields and walnut and almond orchards. Then he watched those lands being sold to developers who chopped down the trees and tore up his former stomping grounds.

“I grew up with that loss,” he says, “but at the same time there were these people around saying that you could actually do something about it.”

He celebrated the first Earth Day in 1970 with his high school biology teacher, who later helped him attend college via a small grant for books and tuition. Simultaneously, a group of older environmentalists (whom he fondly calls “the Wizards”) took him under their wing as they established the nonprofit Save Mount Diablo. By age 19, Doyle was testifying before legislators in Sacramento about preserving land surrounding the East Bay’s iconic peak.

“I bore witness to huge successes,” he says, “and to the Wizards’ tenacious drive to never give up. I saw what that can accomplish.” Those hard-fought battles led to a dramatic increase in the size of Mount Diablo State Park.

Like many other young staffers of that era, Doyle got his start as a part-timer in 1973 cutting down those dead eucalyptus trees in the ridgeline parks. Two years later he took a permanent full-time job as a groundsman at Point Pinole Regional Park.

But his work in the field wouldn’t last long. The park’s upper management knew about Doyle’s successful activism, and in the wake of a new emphasis on conservation (and the requirement to comply with the new environmental laws) the district needed help. In 1978, Chief of Plans, Design, and Construction Lew Crutcher asked Doyle to take a temporary position in the main office to learn about a new form of documentation required of developers called an environmental impact report. Then in 1979 the park’s chief of land acquisition, Hulet Hornbeck, decided to link many of the parks through a trail system and recruited Doyle to handle everything from planning trails to buying and negotiating rights for the lands the trails would traverse. Doyle went on to spearhead the creation of the 28-mile-long Ohlone Wilderness Trail and many others.

When Hornbeck retired in 1986, Doyle was tapped to take over. Among his first challenges was the protracted battle for a secluded valley just east of Mount Diablo. Round Valley had a creek wending along its floor, with lovely valley and blue oaks growing on its hillsides. It was owned by Jim Murphy, the cantankerous son of the original owner, an Irish immigrant who had purchased the land in the 1870s. Now Murphy was looking to sell the ranch, and a group of developers wanted to buy it and turn it into a dump for the fast-growing suburban communities of east Contra Costa County. Murphy was outspoken in his dislike of government, but Doyle knew he loved the property and didn’t want to see it ruined. So Doyle worked to build a relationship and eventually offered to option the property for a year and promised to set aside funds for the full purchase in an upcoming bond measure.

In 1988, Measure AA garnered the two-thirds majority it needed, giving the district $226 million, including the funds for the purchase of Round Valley. It was the largest local bond measure of its time and it transformed the district. Doyle says it was like “getting tied to the nose of a rocket.” For the next 24 years, Doyle oversaw the acquisition of some 48,800 acres of parkland, often taking the battle to court to keep the properties out of the hands of developers. “I don’t think the environmental movement is generally looked at this way, but saving land is a competitive sport,” he says. “You fight hard but play fair.”

In 2010, Doyle was selected to take over the district’s top position, general manager. When he looks back over his four decades with the district, he says, “I hope the public understands how lucky they are that there were so many groups at the same time working to protect special places. They were getting the best of the last. It really could have gone differently.”

Alison Rein

HIRED 1981 / RETIRED 2013

Alison Rein uses one word to describe the state of Alvarado Park—the northern, urban tip of Wildcat Canyon Regional Park—when she started working there in 1989: scary. It was a hot spot for drug dealing and theft. Public drunkenness was common. The facilities were vandalized. The landscape suffered from neglect. It was a sad sight for a park whose infrastructure had been so beautifully crafted by Works Progress Administration workers in the 1930s.

Reclaiming urban parks isn’t what entices most people to work for the park district, but as cities grow it’s an increasingly important part of the job. Rein was no stranger to watching towns balloon in size. She grew up in Houston and on family vacations in state and national parks developed a taste for the outdoors. Not long after completing her undergraduate degree in park and recreation administration at Texas a&m, Rein moved west and took a groundsperson job with the park district in 1981. She began at lake-oriented Del Valle Regional Park south of Livermore; a year and half later she was transferred to the Tilden Nature Area, where the job at that time included helping out at Wildcat Canyon Regional Park.

After the park district took over the Alvarado area from the city of Richmond and connected it to Wildcat Canyon in the late 1980s, regular patrols were instigated to address the serious security issues. Meanwhile, Rein and the other rangers set about removing a derelict playground, ultimately replacing it with a new one and adding picnic sites and a gazebo. Because of the wpa stone masonry the park was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1992. A major effort was undertaken to shore up the creek walls and add boulders and logs to restore its natural look.

Rein says watching that transformation unfold over more than two decades with the Wildcat crew has been “wonderful; it makes me feel really proud.” Other than her early days at Del Valle, Rein spent the rest of her 32-year career in Wildcat Canyon and adjacent Tilden Nature Area, starting as a ranger and rising through the ranks to become park supervisor in 2005. The chance to observe the land’s ebb and flow over decades—explosions of wildflowers, the evolution of open meadows into chaparral, saplings growing tall, and creeks carving new paths—is what drew her to a career in the outdoors. “If you watch long enough and closely enough, you’ll be rewarded with some answers” about the workings of nature, says Rein. “But some things will always remain a big, beautiful mystery.” She has also watched the parks’ popularity swell. “It’s a mixed blessing. People have flocked to the park. It’s packed now.” In the early days, during the week, you wouldn’t see a soul, she recalls. That has changed, and she estimates Alvarado Park’s revitalization has increased the number of visitors more than fivefold in the past two decades.

Rein considers making and keeping the park accessible among her most important achievements, even when it has meant spending many hours at public meetings on matters such as adding additional parking spaces without impacting local residents. It was perhaps not the most fun part of the job, but it advanced the public’s ability to use the park, a fundamental tenet of the district’s mission.

“What the district and its staff provide is sanity for the people of the Bay Area,” says Rein, gesturing to Wildcat Canyon. “If you have this and can walk around for four hours and feel like you’re in the middle of nowhere, when you’re really just 15 minutes from home, that’s everything.”

Victoria Schlesinger is a Bay Area-based environment and science journalist whose work has been published by numerous outlets, including Harper’s, Audubon, and the New York Times. She’s also the author of Animals and Plants of the Ancient Maya (University of Texas Press, 2002).