Liam O’Brien went from Broadway actor to butterfly observer … and then some.

Remember, they are an exotic species in the Western United States, and are rapidly increasing their geographic range and range of habitats. Are they outcompeting or excluding native species in the process? How would we know? We have done almost nothing to monitor changes in the assemblage of mushroom species in areas before and and after the incursion of death caps.

Further Reading

Pringle et al, “The ectomycorrhizal fungus Amanita phalloides was introduced and is expanding its range on the west coast of North America,” Molecular Biology 2009

Lockhart et al, “Simultaneous emergence of multidrug-resistant Candida auris on 3 continents confirmed by whole-genome sequencing and epidemiological analyses,” Clinical Infectious Diseases 2017

Battalani et al, “Aflatoxin B1 contamination in maize in Europe increases due to climate change,” Scientific Reports 2016

Insect Decline?

Bay Nature’s Spring 2019 magazine explores the much hyped “insect apocalypse” through the lens of local scientists, naturalists, and artists.

- What Do You Do About the Insect Apocalypse?

- Meet a Butterfly Illustrator and His Three-Year Project to Paint the Gossamer-Wings

- The Surprising Story of the Color in a Butterfly’s Wings

A successful stage actor into his 30s, O’Brien left New York for the Bay Area as an understudy in ACT’s Angels in America. One day a tiger swallowtail flew through his yard in San Francisco’s Duboce Triangle and he fell under its spell. He bought a field guide, joined the Lepidopterists’ Society, and took the advice of UC Berkeley emeritus entomologist Jerry Powell, who says, “Learn where you live.”

After several “gonzo” years studying up on Northern California butterflies, O’Brien teamed with the group Nature in the City on a project to build a new flying corridor through San Francisco for the green hairstreak, an electrically hued species endemic to coastal Central California. Thus planted in the field of butterfly conservation, O’Brien has moved on to a full career in butterfly monitoring, conservation, and outreach.

As he works, he fills small lined-paper notepads with elegant handwritten observations and paintings, which you see all around these pages. O’Brien’s art adorns numerous signs throughout San Francisco parks, including Glen Canyon and Mountain Lake.

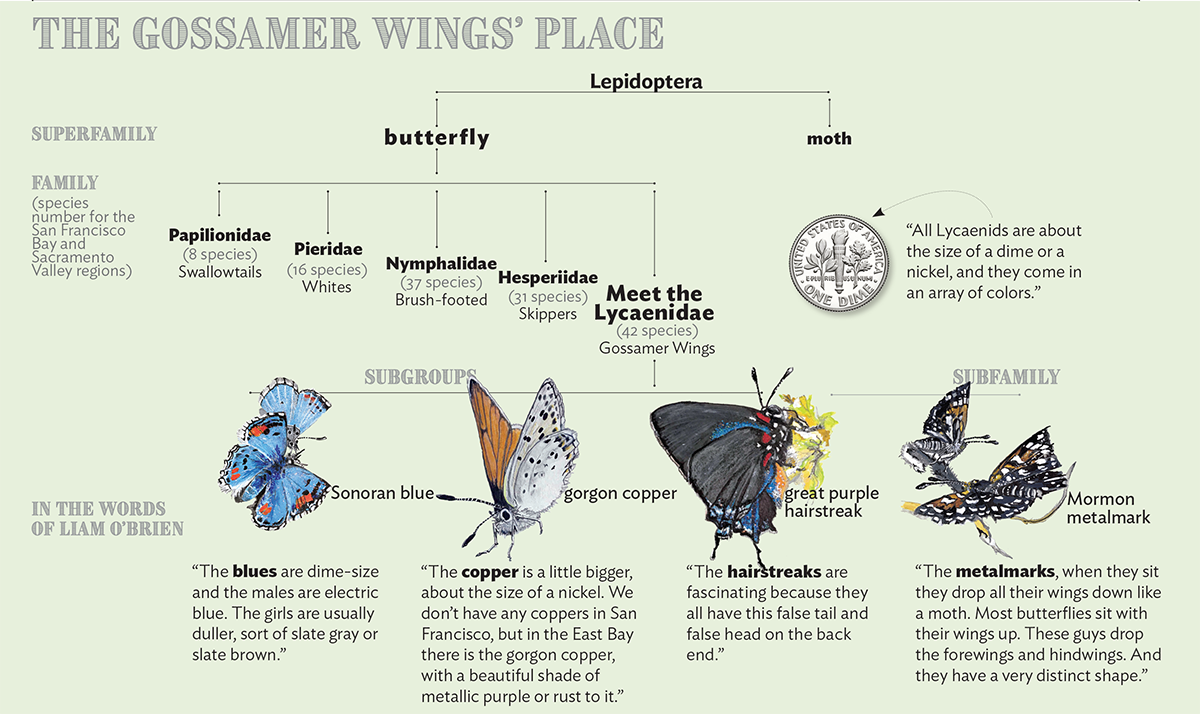

Several years ago, O’Brien was leading a tour on San Bruno Mountain to look for an endangered butterfly called the San Bruno elfin. The elfin is a mostly anonymous brown creature about the size of a nickel. It lives for about two weeks on its host plant, a succulent called stonecrop. Except for its endangered status, there’s not much obviously remarkable about the San Bruno elfin. But O’Brien finds it so, and as he led his tour it occurred to him that the elfin was just one of an entire family of butterflies, the Lycaenidae, or gossamer-winged butterflies, each with fascinating stories, all of them overshadowed by more charismatic cousins.

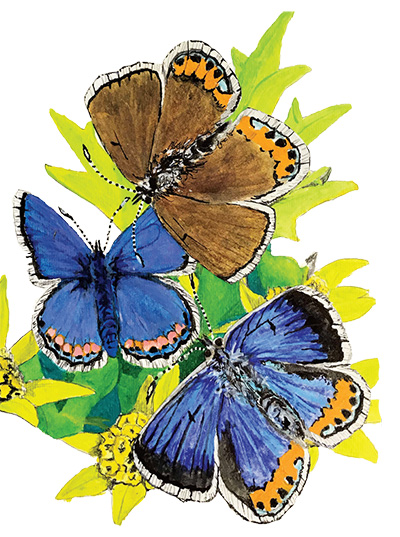

O’Brien likes to quote his brother, who tells him, “Liam, you don’t do anything half-assed.” He decided, then, to undertake a multiyear project to paint each of the 45-odd species and subspecies of Lycaenids in the greater Bay Area. (O’Brien includes the metalmarks as a subfamily, Riodinidae, within the Lycaenids; some taxonomists move the Riodinidae to their own family.)

“Why this group?” O’Brien writes in an introduction to the project. “Well, four of them in the Bay Area are endangered; also, one of them, the ‘coastal’ green hairstreak (C. viridis), actually changed the trajectory of my life.”

A painting, which he keeps in his notebooks, can take five days, he says; it requires an act of deep witnessing. O’Brien observes the butterfly in the wild, studies specimens in his personal collections, and takes photos. He sketches and paints primarily using watercolor pencils and the technique called gouache.

“My colored pencils push through the world of photographic reality for a reason: I am a political stickler for detail for butterflies,” he writes. “Working from photos helps me learn the important field marks, and it removes the impulse to paint butterflies in a fantastic way. What they really look like is paramount in learning each individual’s conservation needs.”

The Lycaenid project has taken three years and three books and is four butterflies short of finished. A close study of one of the many overlooked insect families of the world has taught O’Brien a lesson in what we lose through inattention. “I’m going to miss the unique dots, spots and dashes I’ve discovered in this mysterious world,” he writes. “It put what I used to consider plain into a meat grinder of pretty, and what I considered beautiful into the ethereal, short-lived realm of ‘Please notice me.’”

The Lycaenid Project: Words and Illustrations by Liam O’Brien

Scissoring

“The butterfly can twitch its back end—that’s called scissoring; it’s pulling the predator’s eye to the back. As they’re being bit in the back, they can exit in the front [fly forward]. It’s only within the Lycaenids you see this behavior. It’s built in. They’re not doing it—it’s involuntary. I always tell people it’s the equivalent of misdirection in magic. The magician is doing this and you don’t see what he’s doing … Acmon blues, pygmy blues, and hairstreaks do it too.”

The Ant Relationship

“Some of the Lycaenids have a symbiotic relationship with ants: the Acmon blues, the Mission blues, the green hairstreaks as well. The ants protect the caterpillars. When caterpillars walk up the host plant, the ants don’t run them off like they do most things on a bush. They tend them, like a sheep farmer…they use their antennae to massage the back end of this caterpillar, and out comes a globule of honeydew. They get honeydew from the caterpillars and the caterpillars get protection from other things walking around on the plant.”

Lange’s Metalmark

“The Lange’s metalmark lives out at the Antioch Dunes National Wildlife Refuge. It’s the first piece of land in the country set aside for the protection of an [endangered] invertebrate.” Three other Lycaenids are endangered in the greater Bay Area: the Mission blue, San Bruno elfin, and Smith’s blue.

Western Pygmy Blue

“The western pygmy blue is our smallest butterfly in the United States. The girl is about the size of a dime, but the boy is about one-fourth the size of a dime, if you can imagine that. Insanely tiny… they’re a marsh butterfly. They use pickleweed, Suaeda, and saltbush.”