Photos by David Liittschwager. Text by David Liittschwager and August Kleinzahler

The project started with a question: How much life can be found in a small piece of the world, in just one cubic foot, over the course of a day? If you examined and photographed the complex life it held, what would that life look like? I wanted to photograph, as precisely and faithfully as possible, every creature I found in that cube. And I wanted very diverse habitats, so I consulted with biologists and botanists and finally decided on five: a coral reef, a freshwater river, forest leaf litter, a cloud forest canopy, and shrubland. The photographic work, generously supported by National Geographic magazine, occupied me from Octdober 2007 to September 2008.

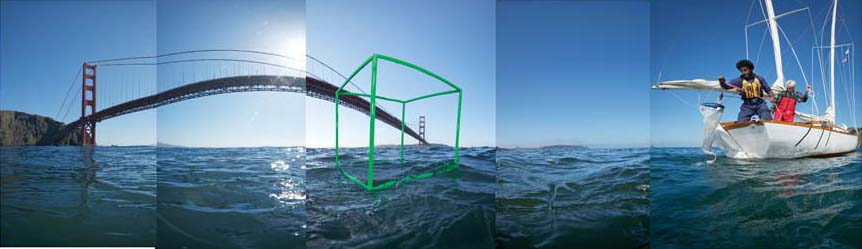

Then, in 2011, supported by the David Brower Center in Berkeley and the For-Site Foundation in San Francisco, I decided to add a sixth habitat. I wanted to “localize” my experience, to find a habitat that was close to home, was part of my neighborhood. Early on in the habitat quest, one consultant had suggested an open-water habitat, and since I live in San Francisco, the Bay seemed ideal. The cube would go under the Golden Gate Bridge, where the confluence of ocean currents and terrestrial run-off creates a rich marine stew. Now, I can’t drive across the bridge without recalling what the cube revealed.

David Liittschwager, Photographer

[slideshow exclude=”86651″]

A couple of turkey vultures, wings unfurled like spinnakers, dry and groom themselves in the late morning sun atop Yellow Bluff.

Beyond them the deck of the Golden Gate Bridge vibrates with automobile traffic: sedans, hatchbacks, El Caminos, Priuses, Cabriolets, blue, red, white, gray, black, countless variations thereof—forty million a year, nowadays, around two billion total since the bridge went up in April 1937.

On the day before the summer solstice, the weather unseasonably warm and still, the 28-foot ketch Argo makes its way out of Sausalito’s Pelican Harbor and into the channel. It’s quiet out there. That automotive buzz on the bridge is gone here. We’re caught up in other elements, wind and water, and it’s the sails and tiller that preside—and, of course, Captain Windrow, who, though vigilant, seems none too concerned, especially on a sweet morning like this.

It’s not always sweet out here, as the writer Jack London knew well. He’d been an oyster pirate on the Bay in his early years, and later chased the same pirates as part of the state’s fish patrol. “San Francisco Bay is so large,” he wrote, “that often its storms are more disastrous to ocean-going craft than is the ocean itself in its violent moments.”

The Bay is very large indeed: With a surface area of some 400 square miles and two trillion gallons of volume, it is the biggest estuary in the western Americas, draining over 40 percent of the land area of California. On each day’s tide more than seven times the amount of water flows through the Golden Gate than flows out of the Mississippi watershed. And instead of opening delta-like to the sea like the Chesapeake and other great estuaries, it is funneled through a narrow, mile-wide passage at the Golden Gate, where it meets the ocean.

“It really blows on San Francisco Bay,” London wrote in 1912. It starts blowing now as we head out under the bridge on the tail end of a big ebb and throw the nets out just off Kirby Cove, near the north tower of the bridge. The nets are 330-micron mesh for the zooplankton, 80-micron for the phytoplankton.

We pull up a sample, brown-colored, dense with life. Here, at the eastern edge of the northern Pacific, is one of the richest, if not the richest, near-shore habitats on the planet: 550,000 creatures in the sample, 2.6 billion creatures passing through one cubic foot over the course of 24 hours . . . just a tad busier than the Golden Gate Bridge over the course of 74 years. Saltwater mites, barnacle and worm larvae, diatoms, porcelain crab larvae, tiny jellyfish, pteropod eggs, possum shrimp, marine gastropods, hydrozoas, snails, amphipods, gyroscope-shaped whatnots.

There are some 2,500 stars visible at any given time in the Milky Way, and about 200 to 400 million that we can’t see. A mariner like Captain Windrow might not know the particular numbers, but he’d have a ballpark notion. He could, no doubt, steer by those stars if he chose to, but it’s my guess he likes to just kick back and stare at them for no good reason now and again. And because he’s no stranger to these phyto- and zooplankton junkets, it probably doesn’t elude him that all that blinking and whatnot happening above is happening underneath his hull as well, in its own fashion. I suspect it’s a great comfort to the captain knowing of so much going on around him, above and below, and none of it having anything to do with him.

It’s all a bit much to try to digest, the wiggling, living sutra of a drop of the Bay. Just about one drop of water from out there by Kirby Cove would seem enough to give most anyone pause, a rather long pause.

August Kleinzahler