Not a very burly building” is the way planner Maggie Wenger describes the Hayward Shoreline Interpretive Center. It’s a homey, roomy place crafted of wood and seasoned by Bay fog and salt spray—the kind of structure you’d imagine Roosevelt’s WPA crews might have built in a national park. It sits on short stilts right in the middle of an 1,800-acre marsh, as well as squarely in the memories of thousands of schoolchildren and other visitors who’ve come here to learn about the Bay. The Hayward Shoreline is both a beloved open space on Alameda County’s heavily urbanized bayshore and one of the low-lying assets that planners like Wenger know are most at risk from sea level rise. “It’s already in trouble,” she says. “When there’s a king tide or a storm event, their trails flood. And they can’t take kids on flooded trails. So it’s not just about the building. They need trails and they need marshes or they’re not going to have anything to interpret.”

I’ve never met her, but Wenger sounded pretty gung-ho over the phone for a point person on the San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission’s (BCDC) advance team on sea level rise. She isn’t the only one. Everyone I interviewed for this story seemed to have moved on from the “doom and denial” phase of the climate change conversation to constructive, creative talk about how to adapt to the up to five feet of sea level rise projected for the Bay Area by the end of the century. As Save the Bay’s restoration manager Donna Ball put it, “I like a challenge, I like a puzzle.”

The trick is, the pressure is on. We’ve built our cities right up the edge of the Bay, and it’s a big Bay so there’s lots of low-lying waterfront. More than 270,000 homes, hundreds of miles of roads and bridge approaches, two international airports, 22 sewage plants, and most of the public access sites on the bayshore are in the flood zone, according to BCDC. No wonder the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) put the Bay Area on its top ten list of American metropolitan areas most vulnerable to sea level rise.

Right now the Bay is only rising by about a quarter-inch per year, a rate double the 20th century average. Within the next 15 to 20 years the rate is expected to speed up dramatically. Overall, the National Research Council projects a 5- to 24-inch rise for San Francisco Bay by 2050, and 17 to 66 inches by 2100. So this is not something we can put off for the grandchildren anymore. “We don’t want people to get to the point where they want the security of a big sea wall. We want people to have other solutions to go to that feel just as safe and don’t cut them off from the Bay,” says ecologist Letitia Grenier, shepherd of a forthcoming roadmap for local adaptation.

There isn’t much resistance. In the last two years, Marin, Alameda, Contra Costa, Santa Clara, San Francisco, and San Mateo counties have all taken steps to get with the program, and numerous existing flood control projects have added sea level rise to their agendas. “On a weekly basis someone asks us to make a presentation, or calls our help desk for advice, or wants us to start the conversation in their county,” says Lindy Lowe, senior planner in charge of BCDC’s Adapting to Rising Tides project (ART). “It’s a sea change in attitudes to adaptation.”

ART has developed a step-by-step process that can help shoreline communities scope out what’s at risk and then select a response. Hayward’s shore made perfect fodder for a demo. “It’s really low-lying,” Wenger says. “You have parks backing up to habitat, backing up to utility lines and wastewater plants and the San Mateo Bridge landing. So if you start moving any one piece, it’s a lot of people at the table.”

In Hayward’s case, they brought Caltrans, East Bay Municipal Utility District, city and county officials, and the parks people to that table. The group decided resilience and recreation were just as important as the economic value of the industrial zone at the water’s edge. They also recognized that their existing levees and flood control protections were not up to the task.

The group is currently exploring the idea of building a new more habitat- and wetland-friendly levee. They invited four engineering students from the University of Santa Clara to visit the site and get the lay of the land. For their senior project, the students will design and present four different approaches, both for experimental softer levees and hard walls as needed. “The Hayward group understands that trying to find a solution that brings together habitat and utility infrastructure and flood protection ends up a lot better for everyone, in terms of costs and benefits, than any other possibilities,” says Wenger.

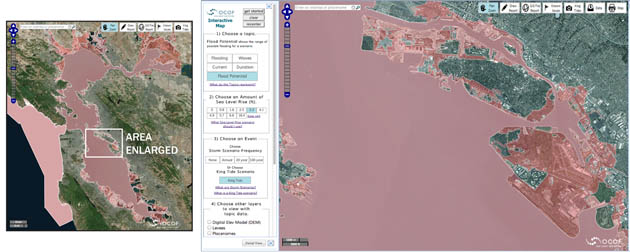

BCDC’s step-by-step ART process goes online this January with a new, more intuitive website. But the real buzz these days is about the “flood map” produced by NOAA and Point Blue Conservation Science under the “Our Coast, Our Future” project. Click on this new interactive tool and the Bay Area pops up on screen, and what you notice first is the light blue ring around the Bay that’s vulnerable to the advancing sea.

The new tool lets you type in any location around the bayshore and see the impacts of various likely scenarios—from different degrees of sea level rise to wave heights and the flooding potential from a constellation of extreme tides, storms, and rising seas.

Being self-absorbed, I choose the “flood potential” option and zoom in on my haunts. Turns out living on one of San Francisco’s seven hills keeps me high and dry. But the Safeway where I shop down near Fisherman’s Wharf and the route I bike to the Golden Gate are engulfed in pink stuff on the screen— pink being the gentler version of a warning red color, I assume. Worse is the Foster City soccer field my daughter practices on. Most of Foster City, a canal-front town built on fill, is in the pink, as are the glossy glass edifices of Oracle, standing in Redwood Shores just across the canal.

Apart from the flood threat to the shoreline headquarters of more than a handful of Silicon Valley giants, the tool also underscores something the U.S. Geological Survey warned of last year: 90 percent of the Bay’s current wetlands could start drowning by mid-century. “Our natural shoreline areas are our first line of defense and what we’re going to lose soonest. They’re already sitting in water,” says Lindy Lowe. “But we can’t forget that they offer both onsite and offsite benefits. So we’re not just talking about losing species, habitats, water quality benefits, views, and Bay Trail experience; we’re also talking about the flip side—the job these natural areas are doing protecting our lives and property.”

Another tool, scheduled for release in early 2015, is an update to the 1999 “Baylands Ecosystem Habitat Goals.” This timely update taps the expertise of more than 200 scientists and resource managers and is funded primarily by State Coastal Conservancy.

The original “Goals” report was a regional call to action to restore 60,000 acres of tidal wetlands around the Bay. The document spawned an unprecedented push for ecological restoration in a shore zone that had lost 85 percent of its historic wetlands to farms, cities, ports, and military bases. Over the last 15 years huge, new, carefully planned and constructed mosaics of fledgling habitats—like Marin’s former Hamilton air base and the North and South Bay salt ponds—have been reopened to the tides, resulting in 13,000 acres restored and 30,000 more planned. Add this to existing wetlands, and the region is on the way to the 100,000 acres deemed necessary for a healthy ecosystem.

But since the report came out the rising sea has made our wetlands—and our goals for them—a moving target. Unlike the stalwart walls of Yosemite or the Grand Canyon, these are soft, vulnerable places shaped and shifted by water and weather.

“As hard as it was to get things restored 15 years ago, it was easy compared to now. All you had to do to get it mostly right was find a bayland with the right elevation in relation to the tides and open the levee,” says Grenier, the update’s point person on new science. “But now, even if you stay on top of the elevation issues, you’ve got to think about watershed management, and freshwater flows, and where you can get more sediment, and how to tackle the other stressors climate change brings. So we need to be more dynamic and flexible in our shoreline designs.”

The goals update is what it says—an update based on lessons learned and the changed climate outlook. It asks how the thousands of acres of restored wetlands and their surrounding habitats can be made more resilient. In some spots baylands are hemmed in by concrete, but in others there are opportunities for adaptation. It might be an old creek bed or an ancient culvert in need of an upgrade. It might be a pasture or a parking lot or a retired oxidation pond at a sewage plant. Or there might even be some open space on the inland side of the marsh rather than a wall of bungalows and tech-hives. All of these places are now opportunities for what scientists call transition or migration zones—room for habitats to spread inland or upstream away from the advancing tides.

The goals update reads well, even in draft—it’s organized and to the point and includes subregional to-do lists and 32 case studies, along with myriad recommendations. A whole new chapter discusses transition zones and how to build them, whether it’s a barrier beach assembled from oyster shells, a wide vegetated levee, or a meadow fed by treated wastewater, among other ideas. Other chapters explore what might happen to wildlife. “If we manage for single species we might lose much more than if we manage to sustain functioning ecosystems. We need bigger patches of habitat, and they need to be connected by more than just a fringe marsh or a denuded creek so animals can move around the Bay and up into healthy creek corridors as conditions change,” says Grenier.

Grenier is most excited about a new focus on making creek connections to the baylands more natural—many are unnaturally encased in concrete. Doing so may offer more transition zones and more places to create fresh or brackish water marshes. “They build up faster than tidal marshes,” says Grenier, giving them an elevation advantage in the face of floods from harsher storms or higher tides. Restoring creeks—many of which have been dammed and altered to control flooding—could also help deliver more sediment from the tops of watersheds to the drowning shore.

“There’s tons of uncertainty—if we have a smaller rise in the seas and a bigger supply of sediment we might be fine, but we should plan as if we won’t,” says Matt Gerhart of the Coastal Conservancy. “With the goals update, we have a roadmap for experimenting and testing ways to move whole landscapes.”

Beyond the enormous benefits of wetlands as sponges for a swelling Bay, many people are at work on a variety of new kinds of adaptive features in our landscape. Chief among these is the “horizontal levee.” Rather than a stark, steep, bare, rip-rapped barrier between us and the water, these new-style levees would protect us without sacrificing habitat. As proposed by various ecologists and restoration engineers, they would have a wider footprint, featuring a gradual rather than steep slope on the bayfront, as well as vegetation and refuge for wildlife fleeing high water. In a way they would compress a whole range of habitat types that would otherwise be lost—from mudflat to marsh to upland—into a much smaller space.

A couple of prototypes of horizontal-style levees incorporating transition zones have been built in the North Bay, and several more complex designs are on the drawing boards. At the Sonoma Land Trust’s Sears Point restoration site along San Pablo Bay, Ducks Unlimited just built one to protect both baylands and a railroad track. The first phase of this two-and-a-half-mile-long levee is “as wide as a football field,” according to engineer Austin Payne. If you lined up all the trucks necessary to bring in this dirt, they’d reach from San Francisco to San Diego.

“The levee is floating on top of 70 feet of bay mud,” says Payne. Bay mud is not that solid, a fact engineers took into account in their design. Instead of just giving the levee a gentler slope on one side, they added slopes to both sides. Once the levee sinks a projected six feet into the unconsolidated Bay mud under its own weight, the plan is to push all the extra dirt on the inland side up onto the top so that in ten years, it could be raised without any more dirt trucks. The gentler bayside levee slope, meanwhile, would remain habitat friendly. “The design allows us to stay flexible and control costs in the face of sea level rise,” says Payne.

The horizontal levee is just one innovative addition to the shoreline that can buffer us from waves and extremes. Other useful additions might be more eelgrass and oyster beds, and restoration planting palettes incorporating diverse species that can withstand wider temperature extremes. Also touted by adaptation teams are human-made islands where wildlife can scurry and birds can build nests out of reach of high water.

Forty newish mounds poke out of Oakland’s Arrowhead Marsh, for example, shaped from local marsh soil and native plant material. During the long wait for the completion of these high tide refuge islands, biologists provided local endangered Ridgway’s (aka clapper) rails with an adaptable alternative—floating thatched cabanas.

A different kind of bird island—this one designed for nesting shorebirds—dots the newly flooded salt pond south of the Dumbarton Bridge. The idea is to provide breeding sites for avocets, stilts, and terns displaced by tidal marsh restoration. After studying bird use of these new features, the USGS rewrote the recipe for success. “Lots of islands in a pond don’t seem to support any more nesting birds than a few islands in a pond, so we should be creating a few small islands in as many places as we can,” says USGS’s Alex Hartman.

One point is clear—whatever lessons learned and new tools we have to work with, shoreline managers also have a whole new set of responsibilities. “Park districts and nonprofits and birders and people who care about shoreline habitat are realizing they’re going to have to go back to places they thought they had already restored,” says BCDC’s Wenger. “It’s a big shift to be thinking less about acres and more about whether this marsh is sustainable or that marsh is going to drown.”

“We need to green the pink stuff, and keep the green stuff from going pink,” says biologist Julian Wood of Point Blue, one of those nonprofits involved in baylands restoration.

Sitting on its stilts in the middle of the pickleweed, Hayward’s Shoreline Center is using its dire straits to good ends. “They’ve done a tremendous job of incorporating sea level rise into their student programs and art exhibits,” Wenger notes. “They see it’s an issue not only for their future but for discussion by the whole community.”

Support for coverage of climate change and sea level rise provided by Google, Inc. and Bay Nature donors.