[callout center]This story is an online companion piece to “Phytophthora: New Strains Breaking the Mold” in the July-September 2015 issue of Bay Nature. Read the magazine piece for more about the discovery and spread of these fungus-like organisms.[/callout]

ff an industrial road and below a span of hills that comprise the eastern span of the Miller/Knox Regional Shoreline in Point Richmond, Watershed Nursery has the air of a prolific, sunny plant nursery.

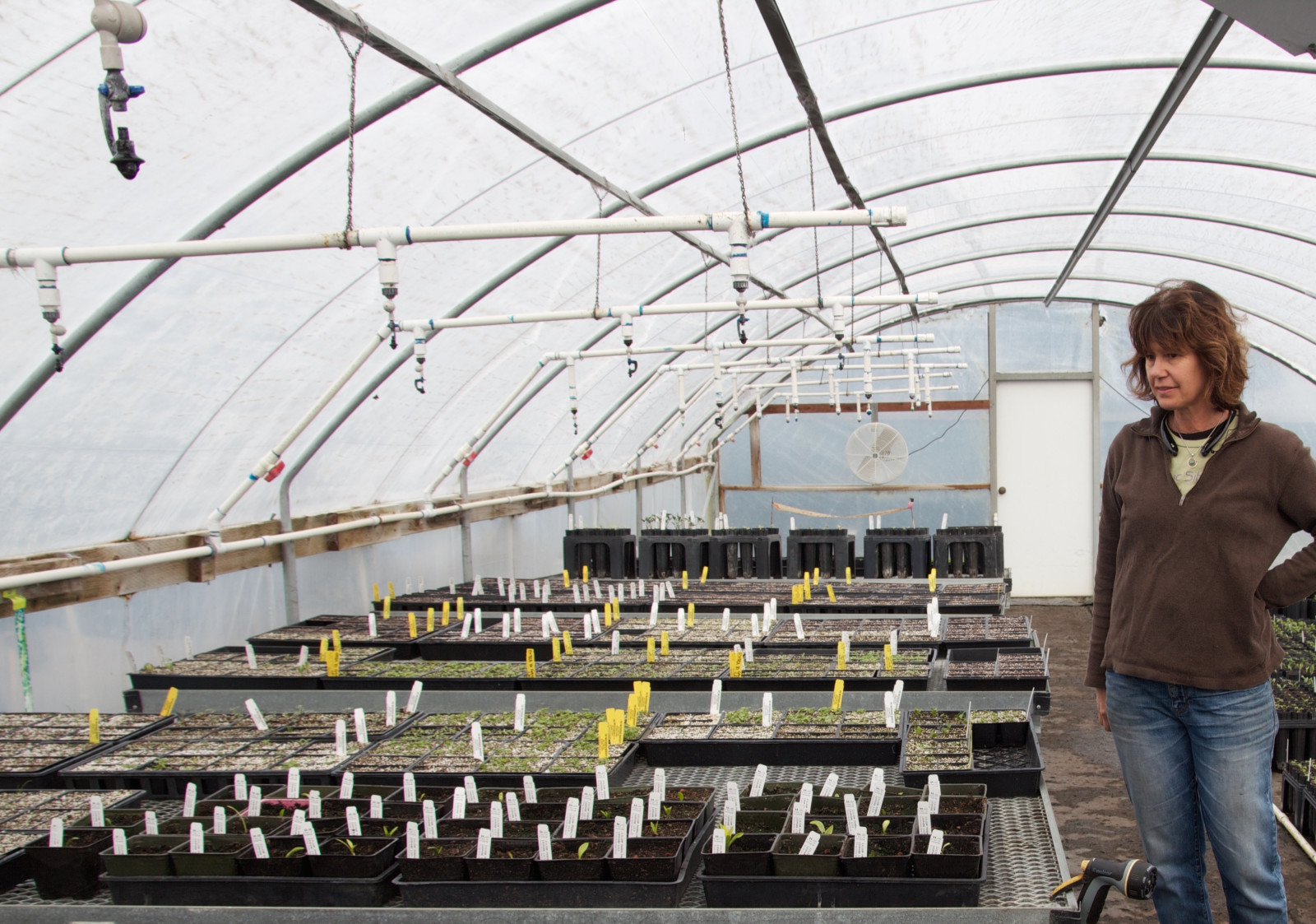

Rows of seedlings poke out of black, plastic containers and a greenhouse smells of moist soil and fresh, green shoots. At the gate, a visitor is greeted by the nursery’s friendly canines — Juma, a Rhodesian ridgeback; Tyla, a rescue mutt; and Pipsqueak, a long haired chihuahua.

Yet, this friendly, native plant nursery is on high alert. A visitor’s first foot onto the property lands on a mat awash in disinfectant, and that’s just the start of many precautions on site.

Emerging from her office trailer, Watershed’s co-owner Diana Benner explains that nothing enters Watershed these days without inspection. Contractors’ trucks have to appear clean, or else receive a power-wash right there and then. Potted plants (Watershed also sells some plants retail) and others materials sit in a covered, quarantined area beside the parking lot if there’s cause for concern.

“It’s like when you’re coming into the country, everything needs to wait there,” says Benner.

Benner has the air of someone who spends her life outdoors, but is down to business when it comes to protecting her plants and the ecosystems in which they will end up. Early last year, she and others in the Bay Area’s habitat restoration community were jolted to find out that a new and dangerous species of plant pathogen — Phytophthora tentaculata — had made its way into a shipment of native plants headed for a restoration site in central Alameda County.

While phytophthora — a group of microscopic parasitic organisms known as “water molds” — have long invaded California landscapes, this particularly pernicious strain exposed a major vulnerability in the supply chain of materials heading into wildlands, in this case, a restoration site managed by the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission (SFPUC). Read Phytophthora: New Strains Breaking the Mold, featured in Bay Nature magazine’s July-September 2015 issue for more about the discovery and spread of these nonnative, fungus-like organisms that move through soil or in water to wreak havoc on crops, nursery stock, and natural ecosystems.

“It’s a total disaster,” says Ted Swiecki, a plant pathologist and consultant to the SFPUC and other public agencies, who examined the shipment of sick plants. “These are rare habitats where we are doing restoration and we’re trying to maintain shrinking populations. We don’t really know how widespread phytophthoras are. We do know that in tests virtually every native plant nursery has been found with one or more species of phytophthoras.”

Since the SFPUC incident, native plant nurseries have been scrambling to tighten their safety protocols. Even so, some restoration managers, including those at the SFPUC, have begun to shun container plants altogether and are instead spreading seeds directly onto wild lands as a safer alternative, a change that could have huge implications for habitat restoration and the economics behind native plant nurseries.

t Watershed Nursery, Benner and co-owner Laura Hanson are building 93 tables to elevate potted plants off the ground, thereby eliminating a risky “splash zone” that can be a vector for disease. And they have set up susceptible plants as “bait” in key spots throughout the nursery to serve as “canaries in the coal mine” to monitor for disease. The most labor intensive work is sterilizing all used container pots in a 60-second ammonia-chloride wash, as well as pasteurizing the potting soil in drums heated with a propane smoker. The soil work alone is an 8-hour-a-week job. “It’s a lot of labor,” Benner says.

Even the dogs are affected: The dirt pile is now off-limits to them. “The dogs love to sleep in the dirt,” Benner says. “So we put up metal fencing to keep them out.”

Perhaps the biggest contribution to the fight against phytophthora has been a call to action in the restoration nursery trade. Benner and Hanson have helped organize a number of get togethers within the restoration community to spread the word about what can be done to stop the spread of phytophthora, and are working with others to set up a certification standard with the California Native Nursery Network for native plant nurseries who achieve best management practices when it comes to preventing phytophthora.

“Watershed has set the stage for a number of native plant nurseries. It has caused a groundswell,” says Karen Suslow, the manager of Dominican University’s National Ornamentals Research Site.

Suslow has worked with Watershed Nursery to adapt a workable set of best management practices to stem the spread of new types of phytophthora in mid-sized nursery operations. Ultimately, though, Benner says she believes the costs associated with preventing these pathogens from spreading may change the face of the native plant industry. Small-scale production of native plants may not survive.

“I don’t know what’s going to happen to nonprofits and volunteer groups,” says Benner. “I definitely have had some groups like that say to me, ‘maybe we should stop doing any production.’ That may be what ends up happening if they don’t have the resources to make the production up to what it should be.”

It will, perhaps, take the coordinated effort of a larger body like the California Native Plant Society (CNPS) to make headway across the many suppliers and sellers of native plant materials who currently have little incentive, other than goodwill towards wild lands, to change their ways. Steven Goetz, president of CNPS’ Willis Linn Jepson chapter in Solano County, says his chapter has found few suppliers willing to go the extra mile to guarantee pathogen-free soil or wholesale plants for the chapter’s nursery.

“It’s very disruptive (to operations) to demonstrate that you are minimizing to the best extent possible the chances of having harmful diseases in your stock,” says Goetz. “You have to follow procedures like those adopted in the operating room. You have to look at all pathways for disease to enter into your process.”

Goetz’s chapter has asked the statewide CNPS to pass a policy that all plant material offered at chapter-sponsored plant sales be certifiably free of exotic pathogens, something the conservation nonprofit is currently considering.

espite all the best efforts of the native plant nurseries to clean up business, there’s been a pull among some restorationists to abandon container plants altogether, at least for the time being. The alternative: directly seeding restoration lands with the desired species. The move, if it occurred widely, would have huge impacts on the bottom line of native plant nurseries, and on the practice of restoration management.

Not only would the progression of new habitat take longer to establish — add 3 to 5 years by some estimates — but some plants simply don’t take well to seeding. Still, from the standpoint of halting phytophthora, direct seeding offers a compelling alternative. In an atmosphere of uncertainty, the SFPUC is already trying it out.

“Seeds are unlikely to transmit the pathogens so we are collecting seeds and instead of growing them in nurseries we are installing them directly in the soil,” says Greg Lyman, a habitat mitigation engineer for SFPUC. “Nurseries are still involved in collecting the seeds, storing them and stratifying them, and preparing them for planting. It’s not the solution. The solution would be to have more nurseries that could deliver good, clean material.”

Heath Bartosh, a botanist and co-founder of Nomad Ecology, has somewhat reluctantly switched to direct seeding in his restoration work.

“For the record, I want to be able to use container stock,” he says. “I have nursery trade friends and colleagues, and I don’t want to see them take a hit because of the current situation.”

But Bartosh says he needs a guarantee that the stock he is using is phytophthora-free — a point that the nurseries have yet to reach. “Until that happens I’m really gun shy,” he says.

Bartosh acknowledges that direct seeding is not without its problems. Because it takes more time to establish a vegetative cover, Bartosh says he’s had to convince the regulatory agencies and clients he works with to allow for longer monitoring periods of the restoration site.

“It’s tough for a client. If they want to close the books for accounting on a specific project, an 8 to 10 year monitoring period is not something they’re going to be jazzed about,” he says.

Then there’s the problem that some plants — such as manzanitas — don’t spring up unless fire or another disturbance triggers the seeds to sprout. Other restoration efforts, such as fish passage projects, need to establish shade cover immediately to keep the water temperature cool enough for fish.

For these reasons, Theo Fitanides, the former manager of Native Here Nursery in Berkeley, doesn’t think container plants will ever fall entirely from favor. He tends to be non-alarmist when it comes to the future of the native plant industry.

“The main source of phytophthoras is importing plants from outside of the area. Local growing is still the way to go,” he says.

Native Here Nursery, a project of CNPS’ East Bay chapter, is implementing an expanded set of protocols to avoid phytophthora, largely funded through the donations by chapter members (the nursery already has been elevating benches, propagating from seed, and hand watering plants). Fitanides says the chapter is still considering whether to make soil sterilization — which heats the soil used in container plants to a high enough temperature to kill off lurking phytophthoras — a protocol in its operations. Cost is a main concern, he says.

Fitanides casts the issue as one of risk management.

“Some parties think we can provide 100 percent pathogen free plants,” Fitanides says. “It’s impossible. We’re purposely growing things and there are things that grow alongside plants and some of those are pathogens. A huge risk reduction is what I think we can achieve.”

Until then, all it takes is a boot, a muddy tire, or a container pot to unleash phytophthora onto the landscape.

Read more from the Magazine about the discovery and spread of phytophthora.