erkins Canyon descends steeply from the eastern slopes of Mount Diablo State Park. Three miles south of the town of Clayton, this isolated section of the park has only a few miles of trails and no official entrance. Visitors park at a wide spot on Morgan Territory Road and step into a gracious grassland dotted with open-armed oaks. Bluebirds flit from tree to tree. “It has this wonderful pastoral feel,” says Seth Adams of Save Mount Diablo. “It draws you in.”

At least it did before September 8, 2013. That’s when a fire started on private land just north of Perkins Canyon, forcing the evacuation of 100 homes. Smoke billowed from the mountain’s east side, with flames shooting up 80 to 100 feet. “The way it sparked, it looked like fuel burning actual gasoline,” Cal-Fire battalion chief Mike Marcucci later told Diablo magazine. “It burned so angrily.”

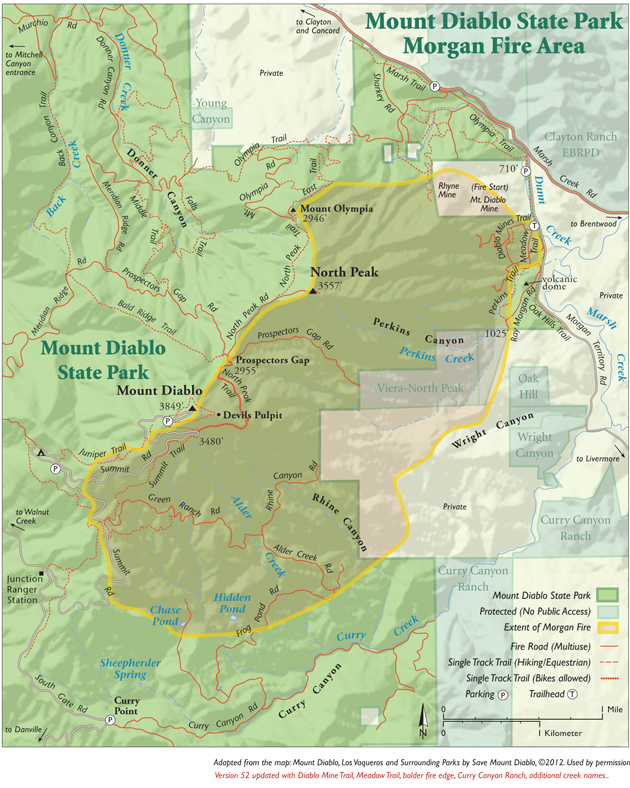

Thanks to an all-out effort (involving 6 planes, 11 helicopters, 25 bulldozers, 142 fire engines, and almost 1,400 personnel), the fire was out four days later. Remarkably, no dwellings or people were lost. But the incident transformed more than 3,100 acres of meadow, chaparral, and woodland on the mountain’s south and east sides, including Perkins Canyon. “It was a once-in- a-generation event,” says Adams — the biggest fire on the mountain since 1977.

Before the fire, I’d been drawn to Perkins Canyon for its giant, mushroom-shaped “volcanic dome,” evidence of a time millions of years ago when magma the consistency of toothpaste oozed up from the earth’s mantle before the mountain itself was formed by uplift. That seemed fireproof enough.

But Perkins had also been a good place to hear a chorus of frogs, splash in the shady creek, and gaze at gorgeous wildflowers. So while I knew, in theory, about the ecological benefits of fire, I couldn’t help feeling anxious about those amenities as I got ready to revisit the canyon a few days after the fire had been extinguished. Adams, who was to be my guide, had driven by earlier in the week. “Prepare yourself,” he said.

was palpable the minute we stepped out of the car. Perkins’ meadow was black and bereft of birds. Heat waves rippled from the ground. The air, though clear, was infused with a stench of smoke. As we walked, dozens of small black beetles we had never seen before bit our sweaty arms and necks.

Adams said that firefighters had been complaining about these “charcoal beetles” (Melanophila spp.), which are attracted to smoke. The beetles court when flames die down and then deposit their eggs in still-smoldering branches. In the mid-20th century, when more people smoked in public, the beetles were occasionally known to invade events such as UC Berkeley football games.

We walked on through the meadow and past several big oak trees, their charred bases encircled with ashes. Their leaves were mostly a toasty brown, with some green on the upper branches. Dozens of acorns fell from their limbs even as we watched. Were the trees living or dead? “The heat may have girdled some of them,” Adams guessed. “But it could take weeks for them to die.”

Some of the slopes above the meadow were completely bare. Others retained a few baked trees in odd fall colors: dusty green, pale orange, and funereal brown. Others were a maze of twisted black sticks. “The mountain’s bones are showing,” Adams said.

Many of the remaining foothill pines (or gray pines) were drained of their usual gray-green color. Also known as “gasoline trees,” foothill pines contain relatively large amounts of n-heptane, a chemical in gasoline. This makes them (and Jeffrey pines) much more flammable than other pines. Their cones explode like hand grenades in fires, spreading flames as they roll downslope.

Oddly, though, what I considered the heart of the Perkins Canyon experience was untouched by the fire. A half-mile stretch of lower Perkins Creek and the volcanic dome beside it were as lush as ever, with healthy-looking oaks, sycamores, foothill pines, grapes, manzanitas, mugwort, and clematis. Wilting from the smoke and heat, I decided to save that mystery for another day.

I came back to the canyon with Mount Diablo Interpretive Association naturalist Ken Lavin. He leads hikes all over the Bay Area for Greenbelt Alliance and is especially fond of Diablo’s east side. “It’s very remote, the wilderness side,” he said. “I could always come over here and find solitude.”

As we walked up Ray Morgan Road, I fumed about the mess left behind by the firefighters’ bulldozers. They had rammed and leveled trees and bushes, making a kind of backcountry highway that was twice as wide and ugly as the old fire road. Yet this was the area that had been spared; there were no signs of fire on either side of the road. The apocalyptic approach seemed unnecessary.

Where a steep new firebreak crossed our path, though, I began to understand. Above the break was charcoal and ashes. Below was the oddly leafy woodland. The fire had roared downhill here on its second or third day, only to be stopped by the work of the swashbuckling machines I’d been cursing. The result was messy, but effective. Nearby homes — the bulldozers’ main concern — had been protected, along with the land around the dome and the creek. This accidental oasis would help reseed the barrens above. It would shelter wildlife, hikers, and horseback riders as the mountain recovered.

Above the firebreak, Lavin and I headed into the barrens on the single-track Perkins Trail. “Before, this was a very wooded area,” Lavin said. “You had to walk with your head on a swivel looking for both rattlesnakes and poison oak. Not so much now.”

I was stunned by a wide sweep of skeletal shrubs. “But fires are not so unusual here,” Lavin reminded me. Some of the original photos in botanist Mary Bowerman’s seminal 1944 book The Flowering Plants and Ferns of Mount Diablo show toasted trees and bushes. In that era, the biggest fires were the two that hit in 1931, consuming 25,000 acres, including most of Perkins Canyon. “There were so many people camping and starting campfires back then,” Lavin said. “It was always the bane of local ranchers.”

The next big fire struck Diablo in 1977. It hit hardest on the north side (including Mitchell and Donner canyons), sweeping across 6,000 acres, but leaving lower Perkins Canyon in peace. After that fire, some local mountain lovers took up a collection to replant the mountain with handsome but out-of-place Monterey pines and coast redwoods. Sanity prevailed, and park personnel planted native species — foothill pines and blue oaks — from local nurseries instead. “That seemed a lot better at first,” Lavin said. “But the nursery trees didn’t have the same genetics as the local trees. And almost all of them died. By that time, the mountain had come back on its own.”

Today the state parks department won’t be reseeding the burned areas. “We take the long view,” says state park re-source ecologist Cyndy Shafer. “We want a natural species composition and density. Planting wouldn’t be appropriate.”

following the fire, each time I went back to Perkins, the canvas — once wiped clean — grew more interesting. A month out, grass was poking up in the meadow; almost every depression had a little patch about one inch tall. Dozens of soaproot bulbs had sprouted, joined by the odd vetch and mustard. Two weeks later, chamise, coffeeberry, yerba santa, and — wouldn’t you know it — poison oak were already beginning to resprout.

The charcoal beetles were long gone. But on one short walk I saw or heard quail, juncos, killdeer, sparrows, scrub jays, black phoebes,

mourning doves, acorn woodpeckers, oak titmice, a couple of vultures, and

a red-tailed hawk. Before the fire, I had

often heard the bouncing-ping-pong-ball song of wren-tits that were hiding in dense chaparral — but had rarely seen

the birds themselves. Now wrentits were hopping around in plain sight in the oaks and other shrubbery.

I found fresh deer and coyote tracks while walking up Ray Morgan Road, and signs of extensive work by rodents rototilling the blackened soil. I asked Lavin what he thought might have happened to a sassy alligator lizard we’d seen before the fire.

“I think he went down a rodent hole,” Lavin said.

“Do you think he’s okay?”

“I’m sure he’s okay. And he probably had a lot of company down there: gophers, ground squirrels, fence lizards, toads, tarantulas, even rattlesnakes.”

The science behind this chummy scene is simple: While chaparral fires generally burn at a withering 350 to 800 degrees F., temperatures are much cooler only a few inches underground. Insulated by soil, seeds and small animals can survive all but the hottest fires.

Not every creature was sheltered when the fire hit, however. Fall on Mount Diablo is tarantula time, when males that have reached maturity (at about seven years old) roam around looking for mates. In fact, Lavin leads field trips just so people can see them. “Tarantulas can move fast for a bit,” Lavin says, “but they have lungs that aren’t well developed and don’t have good stamina. They weren’t going to outrun any fire. So they may have been roasted.”

Where the fire was angriest, no plants may emerge for a while. But over most of the five square miles that burned, Lavin says, we can soon expect a parade of plants. First up will be the grasses, and then a magnificent crop of annual plants called “fire followers,” some of which have been waiting since 1931 to bloom in this area. They come with poetic names — fire poppies, golden eardrops, whispering bells — and fascinating natural histories. Some have seeds that need the chemicals in smoke to germinate. Others’ seeds are cracked open by the fire itself. “Then water can get in with the winter rains, and off they go,” Lavin says.

Bulbs also tend to do well after a fire. At Perkins Canyon, that might mean a banner year for lilies, including elegant brodiaea and the Mount Diablo fairy lantern. Bulbs generally send up leaves each year, but some won’t flower in deep shade. “They’ve got their chance now,” Lavin says. “They’ve been waiting for a fire to burn off the overstory that was shading them out.”

Chamise, like most chaparral plants, can sprout from the crown of its roots. That allows the species to come back faster than shrubs that are killed by fire and depend on seeds to reproduce. Most of the mountain’s manzanitas are nonsprouters (including Mount Diablo manzanita, big berry manzanita, and the common or Contra Costa manzanita; Eastwood manzanita is the lone sprouter) and won’t win any races with chamise. But they’ll still come back from seeds in the soil and in rodent caches. And they’ll be more genetically diverse than their stump-sprouting cousins.

what happened on Mount Diablo in the fall of 2013 was the perfect fire: No lives were lost, no homes were torched, and mostly fire-hardy habitats like chaparral were hit. The end-of-summer timing was excellent. Perkins Creek was dry, so frogs, snakes, and amphibians had already headed underground. Birds weren’t breeding or nesting. Plants were putting energy into their roots rather than their leaves, as they do in springtime. This dryer season not only gives those plants more oomph after the fire; it lessens the danger of a fire that produces steam, which can sterilize soils.

Still, there could be more drama ahead. The steep, bare slopes above Perkins Canyon are poised to erode in this winter’s rains. “The slopes of North Peak contain soils with a lot of clay,” Lavin says. “If we get heavy rains, it’s going to flow, slowly in some spots and faster in others.”

Happily for those who love a good mystery, questions abound. Will most of the big oaks survive? What fire-following flowers and shrubs will emerge this spring, next spring, and the spring after? How long will it take for the chaparral to recover? Were some soils sterilized by extreme temperatures? How much soil will be washed down from those steep, bare slopes?

The 1931 and 1977 fires proved that the mountain’s flora and fauna are resilient. The species and their relative abundance may be different from before, but the meadow, chaparral, and woodland communities will bounce back. Human attitudes are changing, too: This time, there will be no campaigns to replant sizzled slopes with redwoods. Now the parks department is “taking the long view,” and I’m out there with many other park visitors watching natural history unfold in real time. We’re no longer assessing destruction; we’re making discoveries.

“It will be interesting to see what survives and what doesn’t,” Lavin said as we circled back across the blackened meadow to our car. “But I suspect in just a few years it will look even better than new.”

The Perkins Canyon trailhead is on Morgan Territory Road. From the west, take the Ygnacio Valley Road exit off Highway 24. Turn right on Clayton Road, which becomes Marsh Creek Road. Turn right onto Morgan Territory Road. Perkins Meadow, half a mile further on your right, has room for two or three cars to park.

Joan Hamilton is a freelance writer based in Berkeley. She and Save Mount Diablo will unveil an audio guide to Perkins Canyon in January 2014. Seth Adams and Ken Lavin are featured in this and eight other guides in the “Audible Mount Diablo” series.