Looking out from my campsite on the southwestern edge of Dumbarton Quarry, I can see everything. Well, mostly everything. I’m here on assignment and I must admit, the parts of Dumbarton Quarry Campground now open for business are not much to look at: a large, paved area, with concrete islands of grass and tree saplings here and there, and small, narrow spots designated for RV and tent camping, organized into rows and columns. At face value, from looking around, you wouldn’t know all that’s happened here, wouldn’t suspect how interesting this place really is—how a crater with a depth equivalent to the length of a football field was once here; how the Tuibun Ohlone inhabited the surrounding area for at least 2,000 years before the arrival of Europeans. How the rocks beneath us tell a story. I think of an overhead photo of the campground I came across, and my mind’s eye mimics it; my view of the campground starts to elevate slowly, higher and higher, like a drone, until the campground in its entirety comes into perspective. Only then can I really see everything …

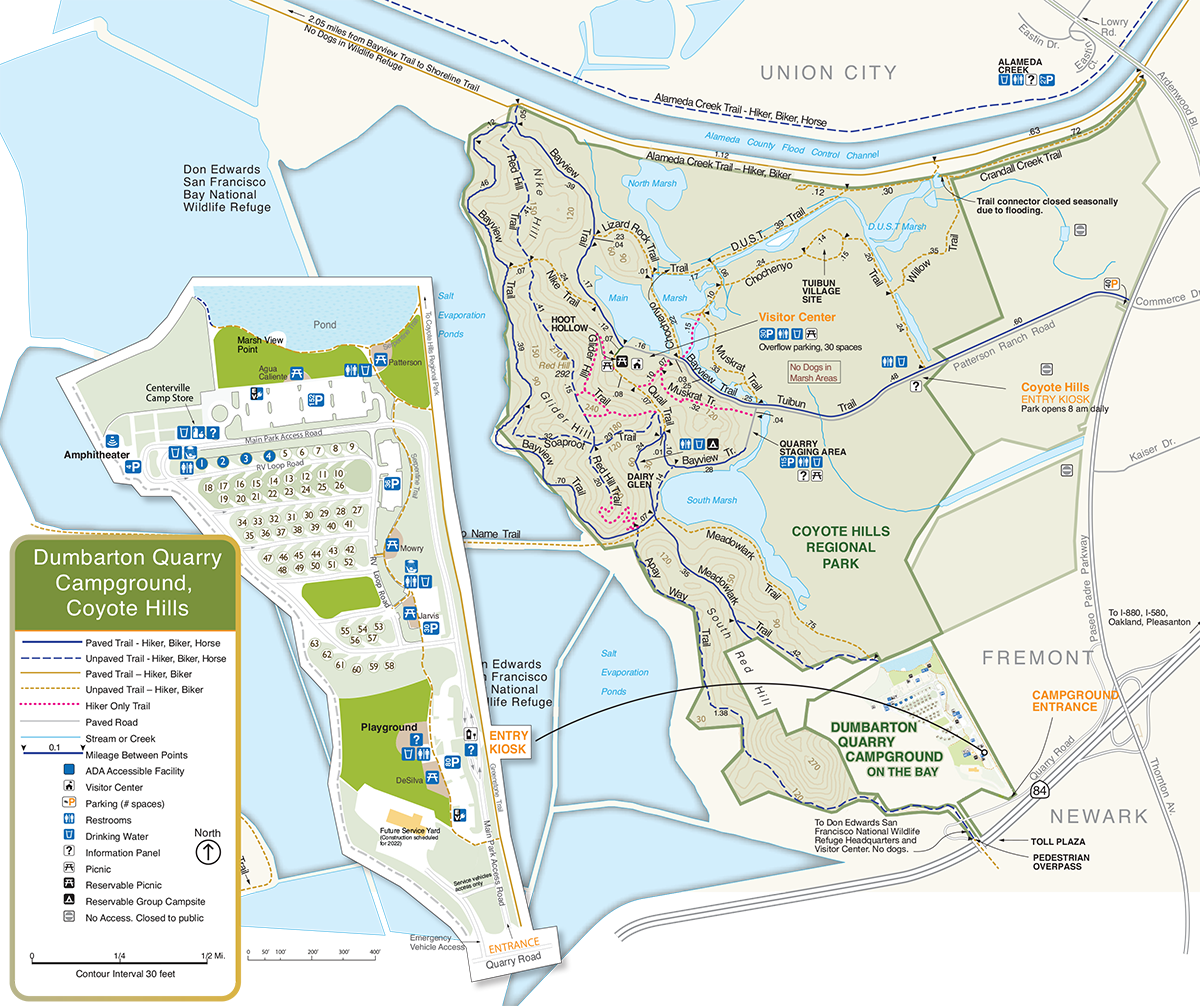

Dumbarton Quarry Campground opened in August 2021. Located next to Coyote Hills Regional Park and next to the eastern shore of the San Francisco Bay in Fremont, it is East Bay Regional Park District’s (EBRPD) first full-service campground near the Bay and the first urban campground in the area in more than 30 years. The site spans 45 acres and contains 63 campsites, a camp store, an amphitheater, a playground, and picnic areas. The quarry itself, which is fenced off and adjacent to the campground, faces the Bay and operated for more than 50 years. After it closed, its developers went through countless stages of planning and development trying to decide the quarry’s future. Even now, the overall campground remains in development, with a phase 2 expected sometime within the next five to 10 years. Despite its in-progress status, there is still much to gain by visiting the site, and there’s even more to learn. I camped there in early October. With its rich geologic makeup and variety of wildlife, this place offers a distinct view of the Bay Area’s natural history—a history, as it turns out, that’s teeming with contrasts.

Before There Was a Quarry

Long before backhoes and cranes emitted a sound here, most of the area now known as Dumbarton Quarry was occupied by Indigenous peoples. Although multiple archaeological village sites exist within Coyote Hills, the closest one to Dumbarton Quarry is called Tuibun, ostensibly the name of the people who occupied it. The Tuibun Ohlone, also known as the Alson, were one of the many Ohlone tribes living in the San Francisco Bay Area. EBRPD naturalists say the Tuibun village site dates back about 2,000 to 2,500 years. The site itself, a relatively intact shellmound, sits east of where Alameda Creek enters the Bay. Today, a replica of a Tuibun house is open to the public.

Due to the effects of Spanish and American colonization, information about the Tuibun Ohlone is quite fragmented. However, they were known as great hunters. According to accounts by Spanish soldiers, the Tuibun Ohlone often traded duck replicas for European glass beads. By stuffing an actual duck skin with tule reeds and putting the decoy in the water, Tuibun hunters could attract and capture other ducks, including canvasbacks. The Tuibun also used tule reeds to make baskets, mats, rafts, and shelters, methods still practiced by Ohlone today.

To speak of the Tuibun Ohlone in the past tense is misleading—the descendants of the Tuibun group, including the Him’ren, Lishan, Muwekma Ohlone Tribe, and Northern Valley Yokuts, are among the tribes with ancestral ties to this area; many live in the region today and continue their cultural practices, which include ceremonies at the Tuibun village site. Since the early ’80s, the park district has worked with Indigenous groups to facilitate holding their ceremonies and to create reproductions of village sites like Tuibun. Though public access to Tuibun is currently closed due to COVID-19 and by request of Indigenous groups, its presence and background give us more understanding of the land’s long and rich history.

The Hole We Created … and Then Refilled

The original quarry land was a ridge that extended quite a distance. “The Dumbarton toll plaza sits in a gap that wasn’t always there,” says Jim O’Connor, EBRPD’s assistant general manager. Before, the hill directly north of the toll plaza area stretched south across to where Don Edwards Wildlife Refuge is now. “That was a whole ridgeline,” O’Connor says.

Beginning in the 1950s, developers started quarrying the area for “rock base,” a mixture of gravel, sand, and crushed stone used in roads and construction. The material went into freeways, buildings, bridge abutments (including the San Mateo–Hayward bridge), and parts of the San Francisco and Oakland airports, among other projects. From the 1950s through 2007, a total of about 15 million cubic yards of material was quarried, transforming the original 190-foot-high hill into a pit that measured roughly 960,000 square feet and reached 310 feet below mean sea level. It was the lowest elevation point in North America at the time.

Remember, they are an exotic species in the Western United States, and are rapidly increasing their geographic range and range of habitats. Are they outcompeting or excluding native species in the process? How would we know? We have done almost nothing to monitor changes in the assemblage of mushroom species in areas before and and after the incursion of death caps.

Further Reading

Pringle et al, “The ectomycorrhizal fungus Amanita phalloides was introduced and is expanding its range on the west coast of North America,” Molecular Biology 2009

Lockhart et al, “Simultaneous emergence of multidrug-resistant Candida auris on 3 continents confirmed by whole-genome sequencing and epidemiological analyses,” Clinical Infectious Diseases 2017

Battalani et al, “Aflatoxin B1 contamination in maize in Europe increases due to climate change,” Scientific Reports 2016

Know Before You Go

» For fees and to book campground reservations, visit the East Bay Regional Parks web page.

» The campground is exposed, so be prepared for wind and sun.

» Currently, three unpaved tent-only sites have water access and 60 paved sites include hookups for water, sewage, and electricity. More camping sites are planned for phase 2.

In 1977, Dumbarton Quarry Associates (DQA), a division of DeSilva Gates Construction, took over the quarry and filed a reclamation plan. The City of Fremont granted a 30-year extension on the permit, which expired in 2007 and led to the quarry’s closure. At first, the reclamation plan consisted of converting the quarry into a lake, but after several iterations they settled on turning the surrounding area of the quarry into a regional park and campground and the quarry hole into a lake. In collaboration with EBRPD, the company began working on that plan in the 1990s. However, there was one problem—nobody could figure out a source for the lake’s fresh water.

In 2012, EBRPD and DQA revised the plan. This time, they decided the quarry hole would be filled to create a meadow. But that plan also proved problematic; the fill material settles over time. And despite efforts to do what’s called dynamic compaction—a ground improvement technique that densifies soils and fill materials by using a drop weight—the meadow would continue to settle over years and could potentially become, again, a hole.

To resolve the issue of settlement, EBRPD and DQA scrapped the meadow idea and agreed in 2016 on a partial re-creation of the original ridgeline, which would involve not only filling the rest of the quarry hole but adding material on top to build a large hill, situated between the Bay and the campground. Finalized in 2017, this plan has stuck.

Developers managed to fill the quarry hole to the surface in 2018 and have been adding material ever since to re-create the ridgeline hill. They expect to finish this second phase of the project within the next few years; the property will then include an additional 28 campsites, along with space for cabins, yurts, and safari tents. At that point, the entire campground will span 90 acres.

Not many areas like Dumbarton Quarry become campgrounds. As O’Connor points out, most Bay Area quarries are now housing developments. “The unique aspect of this project is that it converted the quarry into a regional park to serve the Bay Area and beyond,” he says. “It’s one of only a handful of public campgrounds on San Francisco Bay.”

For me the quarry’s development story alone was interesting enough to make a visit. Huge events, huge history, have taken place within this relatively small patch of land—its beginnings as a home to Indigenous peoples, the forceful removal of those peoples, the gutting of the land for construction of Bay Area infrastructure, the repurposing of the land as an attraction— together embody a social and geological tale of the Bay Area itself. “Knowing” this history is in itself a form of “experiencing” the campground.

Also hard to see but knowable is the stuff the site is made of. And as I soon found out, the campground’s physical composition provides a window into the Bay Area’s geologic past.

The Campground by the Bay

After settling in at Dumbarton Quarry, I head to a large hill on the campground’s northwestern end to meet with Christopher Sulots, the supervising naturalist for Coyote Hills Regional Park, and Ashley Adams, a naturalist at Black Diamond Mines. When I arrive, Chris and Ashley are sifting through rocks. They tell me about the hill we’re standing on. “There’s a little bit of a peak there,” says Chris, pointing at a small hill on the south end of the campground. “Connecting that side to the base of the hill on this side here”—he points below us—“that would have been the original footprint of the quarry hole.” In other words, we are standing on the 50-foot hill on top of the former quarry hole.

To fill the hole, developers used about 6 million cubic feet of material, plus an additional 4 million to construct the hill. And they’re still building. The goal is to build the hill up to a height of around 165 feet. Although material for the campground and hill has come from all over the state, the project got a local boost when Bay Area construction revived in 2018. A large portion of the material that fills the quarry and resurfaced parts of the campground came from local projects, such as the Salesforce Transit Center and Antioch BART station.

“It’s interesting because originally—digging out the hole, getting gravel—all that went out to projects statewide,” says Chris. “And then to re-create this place back into a campground and hill, they started pulling in dirt and fill from projects all over the state. So, everything goes out and then everything comes back. And it’s different stuff that came back in.”

The “different stuff,” combined with the site’s existing geology, makes this a special geologic area, according to Chris. Ashley grabs a handful of rocks to show me. “These rocks are members of a group called the Franciscan Assemblage,” she says. “They were laid down on the ocean floor 200 million years ago. When the North American Plate and the Farallon Plate collided, the Farallon went underneath where we are standing today. As it went underneath, it scraped up the rock on the ocean floor and crumbled it together. So, that’s what we’re looking at—a mixture.”

Ashley points out two rock types: chert and greenstone. Called radiolarian chert, that rock was formed from the remains of radiolarian plankton. Millions of these microscopic critters’ skeletons sank to the ocean floor and eventually became an ooze. Over time, compression solidified and hardened the ooze into the chert rocks, whose rusty red color comes from iron. Greenstone, which gets its color from the mineral chlorite, formed after hot water from hydrothermal vents in the ocean heated an igneous rock called basalt over time. On top of this rock mixture lies sandstone, as well as gravel, which is much younger and made its way down Alameda Creek, filling in the natural divots and grooves of the area.

Today, thanks to the quarry, campers can examine and touch this history. “There’s not many places like this,” Chris says. Ashley agrees: “We’re looking at California’s geologic history, how we came to be.”

A Place of Contrasts

Adjacent to the campground, the trails in Coyote Hills are waiting to be explored. I cut across to the Serpentine Trail, which outlines the eastern side of the campground. Walking north, I notice something—the noise. Or better yet, the lack of noise. Given that the campground is right next to a freeway and not too far from an airport, I expected to hear cars and planes. Thankfully, the only things I hear throughout my stay are the occasional barking of a nearby camper’s dog and the howling wind.

The Serpentine Trail leads me to the Marsh View Point pond on the campground’s north end. The pond acts as sort of a gateway to Coyote Hills. I take another look around the campground and notice a couple of black-tailed jackrabbits springing up the remade hill. A red-tailed hawk circles the area. Other known animal frequenters include Cooper’s hawks, turkey vultures, Western bluebirds, black phoebes, black-necked stilts along the shoreline, and deer. The campground is full of newly planted drought-tolerant species, including toyons and manzanitas. A couple of coast live oaks as well. For now, the campground, due to ongoing construction, doesn’t give clear views of the Bay. But when phase 2 is complete and the hill re-formed, campers will be able to hike to the top and see the Bay and Dumbarton Bridges.

As I make my way to the gravel road, the sun begins to set. Warm orange rays light up the quarry hill, casting a dark shadow over the rest of the campground. The scene reminds me of something Chris told me earlier.

“What stands out about this place are the big contrasts,” he said. “It’s all millions of years old, but it’s also new. Then there’s the contrast of rural and wildlife here, and then urban life right behind you. There’s also the geologic contrast—the incredibly large hills on this very flat terrain. And then, of course, there’s the public and private contrast—this place was a private, corporate quarry, and now it’s a public park. There are a lot of unique contrasts geologically, environmentally, and governmentally.”