“Out in the tules” was a phrase I first heard from a San Joaquin Valley-born college roommate more than 20 years ago. Like a lot of things about California, it was a little mysterious to an expatriate Southerner. It seemed clear from the context that “the tules” was the California equivalent of “the sticks” or “the boondocks,” connoting remoteness and unsophistication. I had heard about Tule Lake, site of the World War II internment camp, and about the treacherous tule fog in the Central Valley. But the connection between these references was not immediately obvious to me.

- A flowering stalk of tule. Photo by J.W. Wall.

Tules, I eventually learned, are just one of California’s 23 kinds of bulrush, specifically Scirpus acutus var. occidentalis. They’re a major component of freshwater marsh vegetation along with sedges, other bulrushes, and cattails. My roommate’s reference was to obscure patches of the state’s interior wetlands, remnants that had not yet been drained, filled, or paved over. Enormously productive marshes once covered great swaths of the Central Valley, including the Tulare Basin (“tulare” is Spanish for “tule marsh”). They supported vast flocks of waterfowl and herds of elk, and were central to the economy and culture of native peoples like the Wintun and the Yokuts. Tule fog remains a winter menace along the valley’s roads, but most of the freshwater marshes where tule grew are now gone. It’s ironic that what used to be such a prevalent and important environment has been so reduced as to serve as a synonym for out-of-the-wayness.

With the current spotlight on conserving and restoring San Francisco Bay’s tidal saltwater marshes, our region’s freshwater marshes have received less attention. But this ecosystem is also threatened, for many of the same reasons. Most of the Bay Area’s historic freshwater marsh habitat has been lost as wetlands have been filled for development and the creeks feeding them imprisoned in concrete channels.

Fortunately, Bay Area residents don’t need to venture “out in the tules” to see a remaining freshwater marsh habitat; they need only go as far as Coyote Hills Regional Park in southern Alameda County, near the east end of the Dumbarton Bridge. Although not a classic tule marsh-in fact, the tules here are in danger of being displaced by the more aggressive cattails-the park’s wetlands harbor a diversity of aquatic plants, including tules, and a complex and fascinating wildlife community that relies on the plants for food and shelter. The tules, cattails, and other marsh plants also sustained the local indigenous Ohlone people for thousands of years and shaped the texture and flavor of their lives. After a varied recent history-the area was once a duck-hunting preserve for the Bohemian Club, then housed a Nike missile base and a biosonar research lab, and was even briefly considered as a site for the Stanford Linear Accelerator-Coyote Hills now shelters a wetlands microcosm in the shadow of the urban East Bay.

The park’s name doesn’t exactly evoke marshlands. The rounded, grass-covered hills are indeed the most obvious feature of the park from a distance, rising unexpectedly out of the flat baylands. They’re the ancient, eroded tip of a tilted fault block, poking out of several hundred feet of alluvial sediments deposited by nearby Alameda Creek. (Brooks Island, Albany Hill, and the island of Alameda are also part of the same block.) The easily climbed summits provide sweeping views of Alameda Creek and its watershed, and broad panoramas of the Bay and the East Bay hills. Where the park lands meet the San Francisco Bay National Wildlife Refuge, tidal marshes, mudflats, and salt ponds provide a haven for the endangered California clapper rail and wintering habitat for multitudes of shorebirds and waterfowl.

- The marsh wren is “the presiding spirit of the marsh.” Illustration by Keith Hansen, courtesy of Nature Conservency of Nevada.

But the attraction of this place for me has always been the subtle beauty of the freshwater marsh. An easy walk brings you close to the marsh’s feathered and furred inhabitants, and gives a sense of the depth of human presence in this part of the world.

The four marshes here-North, Main, South, and DUST (Demonstration Urban Stormwater Treatment)-are the product of 150 years of manipulation by private and public landowners. Back in the 1850s, when this area was first mapped, salt marsh subject to the tidal influence of the Bay wrapped around the back side of the hills, where the freshwater marsh is today. It was fringed on the east by a large willow marsh (freshwater), and on the south by a brackish pond. Seasonal freshwater wetlands stretching to the east were fed by several creeks that meandered down from the East Bay hills. Over time, much of the freshwater marsh was converted to farmland. The area that had been salt marsh was cut off from tidal influence by levees and gates, and gradually transformed into brackish and freshwater marshes.

And the place, like any neighborhood, keeps changing. The “new” marsh is now in danger of being taken over completely by cattails, an issue being addressed by the East Bay Regional Park District (EBRPD) and the Alameda Flood Control District, which jointly manage the area. There are still parts of the park, though, where tules persist, and you can get an idea of what the Bay Area’s freshwater marshes were once like.

- A muskrat chews on a piece of cattail. Muskrats’ appetitefor cattails and tules helps keep open channels through the marsh.Photo by Jeffrey Rich.

A boardwalk across the road from the visitors’ center leads into the marsh. For a short but rewarding loop, bear left onto the Lizard Rock Trail, then left again to return via the Chochenyo Trail. Along the way, curtains of cattails part to reveal open stretches of dark water; there are also scattered stands of tules, other varieties of bulrush, and sedges. Although you’ll see salt-tolerant pickleweed fringing the tidal tributaries of Alameda Creek, the plants here are mostly different from the cordgrass-pickleweed association of the adjacent salt marshes.

Cattails-freshwater specialists-predominate; their flattened leaves and velvety brown, kielbasa-shaped flower heads make them easy to identify. The other plants can be harder to sort out; there’s a helpful visual guide near the marsh diorama in the visitors’ center. The mnemonic device “sedges have edges and rushes are round” oversimplifies things somewhat: Tule stems are generally cylindrical, but some of the other bulrushes resemble the sedges in having stems that are triangular in cross section. The tules at Coyote Hills tend to grow taller than cattails and keep their deeper green when the cattails have turned brown.

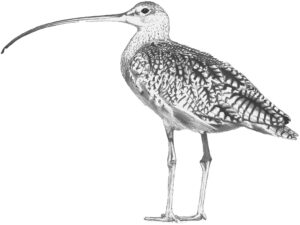

The marsh plants are home and foraging ground for a startling variety of birds. Some, shy skulkers like the American bittern, the sora, and the Virginia rail, rarely leave the shelter of the vegetation. If caught in the open, the brown, heron-like bittern will freeze, neck extended and bill pointing skyward, so its streaked plumage dissolves into the background of brown stems. (I once saw a bittern attempt this in the middle of a road, to less successful effect; that’s one problem with hard-wired behavior.) Open-water birds-like cinnamon teal, pied-billed grebes, and the ubiquitous coots-conceal their nests in the maze of channels that dissect the marsh. Northern harriers, white-tailed kites, short-eared owls, and other raptors patrol the wetlands, scanning for rodents and other small prey. The kites, graceful raptors once called angel hawks, are especially abundant in winter; I spotted six on a recent visit. Yellowthroats and song sparrows advertise their territories from tule-stem perches.

It’s the marsh wren, though, that I think of as the presiding spirit of the marsh at Coyote Hills. The local subspecies has been called the tule marsh wren or, in some of the older books, simply the tule wren. Smaller than sparrows, these little brown reed-dwellers have a disproportionate presence. You’ll hear far more of them than you’ll see, heckling you from within the cattails, though they’ll occasionally pop up for a better look around. When not scolding hikers, the male wrens hold song duels-rattles, gurgles, buzzes, trills-with their counterparts in neighboring territories, each covering about an eighth of an acre. They’re far from the best singers in their family, but they compensate for this aesthetic deficit with the variety of their repertoire: Western male marsh wrens may have up to 210 song types. (Easterners average less than 100, and some ornithologists think this marks them as a separate species).

Between bouts of song, male marsh wrens somehow find time to build as many as 50 oblong nests, 7 inches high by 3 wide, woven from strips of cattail and sedge leaves and lashed to the upright stems of marsh plants. After some inspection, a female picks her favored nest and then insulates it with cattail fuzz. Unlike most birds, which are either ostensibly monogamous (like geese) or non-territorially promiscuous (like hummingbirds), marsh wrens practice simultaneous polygyny, with two or three females nesting in a male’s territory-an arrangement more typical of mammals such as elk or sea lions.

Perhaps the oddest thing about the wrens is their antipathy to red-winged blackbirds. If redwings, which are almost twice the wrens’ size, nest near wren territories, the wrens will sometimes destroy the blackbirds’ eggs or kill their nestlings. I haven’t found a good explanation for this anywhere in the literature. Egg theft is not uncommon among birds, of course-jays are notorious for it-but the wrens don’t always bother to eat the eggs’ contents. Although blackbirds could be competitors for the wrens’ food sources, this would also be true of the song sparrows and yellowthroats, both tolerated as neighbors. In any case, wrens and blackbirds generally avoid each other when they nest in the same wetlands. Redwings are conspicuous enough elsewhere in the park, but the boardwalk area seems to be wren turf, and they proclaim it so loudly and at great length.

Down below all this avian sex and violence, the muskrats lead their own more placid lives. The Coyote Hills population is not indigenous; they may be the descendants of fur-farm escapees. The species’ original range in California did not extend beyond the lower Colorado River and the state’s northeastern corner. But they have made themselves very much at home here. They’ll eat anything that grows in the marsh, and their appetite for tules and cattails helps keep the channels open. Not strictly vegetarians, muskrats will snack on clams, crustaceans, fish, and frogs when they can. Although elsewhere they’ve been known to heap plant material into 5-foot-high houses, the Coyote Hills population lives in burrows tunneled into the levees that surround the marsh. Predation by raccoons helps keep their numbers in check. So does tularemia (so named because it was first described from Tulare County), a disease to which muskrats are susceptible.

Muskrats are reputedly tasty, even if you’re not a raccoon; my battered copy of The Joy of Cooking (1973 version) has a braised muskrat recipe, which has of course been banished from the trendy and sanitized 1997 revision. I suppose the Ohlone of Coyote Hills would have savored them, given the option. Ohlone menus varied from place to place, of course, but archaeological evidence from sites dating back more than 2,000 years shows that the people of this marsh feasted on shellfish and waterfowl, supplemented by dryland game, acorns from inland groves, and the seeds of native grasses.

The Ohlone harvested construction material as well as food from the marsh. At a bend of the Chochenyo Trail, on an ancient shellmound, park naturalists and volunteers have reconstructed a village site, dominated by a tule house-a handsome, tightly woven rounded structure. A replica of an Ohlone boat, built of bundled tule stems and dubbed (unfortunately) the “Kon Tule,” is on display at the park visitors’ center along with actual artifacts found at the shellmound, known to archaeologists as Site Ala-328 and excavated by San Francisco State teams from 1949 until the park opened in 1968. Tule stems also furnished material for household mats and women’s skirts. Other native Californians used the roots of aquatic sedges in their intricately woven baskets.

But what good are tules and other aquatic plants if you don’t happen to be a marsh wren, muskrat, boatwright or basket maker? These plants may have been essential to the Ohlone, but do they have any practical value for contemporary city-dwellers? The park’s DUST Marsh suggests that they do. This project uses wetland vegetation to filter pollutants from storm drains that catch runoff from a 5-square-mile area of Fremont. Tule and cattail stems slow the flow of water so their roots and associated soil bacteria can break down toxic sub-stances. So far this seems to have had no adverse environmental impact; like Arcata’s better-known sewage-treatment marsh, the DUST Marsh teems with ducks, herons, and other birds.

- Map by Ben Pease.

There’s far more to the Coyote Hills wetlands than runoff treatment, of course. Saved from development (including plans for a major pleasure-craft marina) by a series of lucky accidents and the combined efforts of dedicated local residents and East Bay Regional Park District staff, the marsh gives urbanites a chance to see herons and egrets stalking in the shallows, harriers performing their rolling-and-tumbling courtship flights, the wake of a swimming muskrat, or a peregrine falcon stooping on a flock of ducks. As managed by the East Bay Regional Park District, Coyote Hills preserves a piece of a natural California that is mostly gone, and protects and interprets some of the Bay Area’s oldest markers of human presence. And it’s all just a few miles off the Nimitz Freeway.

Getting there:

From I-880, exit west on state route 84, Decoto Road. Turn right on Paseo Padre Parkway, then left on Patterson Ranch Road and proceed into the park. Gates are open 8 a.m. to 6 p.m., with a $4.00 day-use fee. Visitor center hours are 9:30 a.m. to 5 p.m., Tuesdays through Sundays. Call (510) 795-9385 for information on park programs and special events.

.jpg)