You can’t miss Mount Umunhum. If you spend any time at all in the South Bay, you are sure to notice the fourth-highest peak in the Santa Cruz Mountains: It’s topped with an iconic concrete monolith. Locals know the peak by sight, if not by name, as it towers over Los Gatos. The three higher mountains in the chain also rise up right behind, reaching into the bluish haze that gives these mountains their name: “Sierra Azul,” or blue range.

Yet most people are missing what hides in plain sight around the mountain–a sprawling patchwork of open space that’s so little used and so rugged that you’ll feel you’ve discovered a wilderness when you come here for a hike. Golden eagles and mountain lions find homes here, confirming the wildness of the place. But just climb to one of several vista points for an expansive view of the South Bay–and a reminder of the close press of civilization.

The Midpeninsula Regional Open Space District, a public agency created in 1972 to preserve open space in San Mateo and northern Santa Clara counties, was still young when it made the first purchases for Sierra Azul Open Space Preserve. “It’s been a preserve in the making for such a long time now,” says Matt Freeman, planning manager for the district. Nearly 200 transactions later, with some purchases adding only a fraction of an acre, the district has pieced together a preserve encompassing more than 17,500 acres, by far its largest property, constituting about a third of the district’s total holdings.

- Once capped by a large dish, the cube atop Sierra Azul was part of the national air defense system until 1980. Radar operators on the peak scanned out to sea for Soviet bombers. Photo by Jane Huber.

- View north toward the Santa Clara Valley from the Kennedy Road Trail in the Kennedy-Limekiln Area of Sierra Azul Open Space Preserve. Photo by Ronald Horii.

“Sierra Azul really represents an important aspect of our mission,” Freeman says. The agency seeks to create an interconnected network of open space preserves forming a contiguous greenbelt, partly for recreational connections but primarily to protect habitat connectivity so ecosystems can function naturally. Sierra Azul presented just such an opportunity. Although still unfinished and checkered with private inholdings, the preserve connects the Forest of Nisene Marks State Park, the Soquel Demonstration Forest, and Almaden Quicksilver County Park.

Gaps in ownership complicate public access, but even partial access adds up in such a large park, with about 26 miles of trails open now and more to come after the district completes a comprehensive master planning effort later this year. But district policy discourages developing dense trail networks. Instead, large areas will remain undeveloped to provide undisturbed habitat. Sheer practicality also figures in–constructing trails is difficult in such rugged terrain.

Hikes here can be strenuous, with long trails reaching far across the preserve, and if you have talkative knees, they may complain about steepness. But you can find flatter, shorter jaunts, too. And the cooler, clear days of winter are a great time to go, affording some of the farthest views. You can take in Coyote Valley, Mount Hamilton, and the East Bay. Or gaze up the Peninsula all the way to Mount Tamalpais in Marin.

- The varied habitat of Sierra Azul Open Space Preserve, the largest in the Midpeninsula Open Space District, is more than big enough for resourceful coyotes to thrive. Photo by Enrique Aguirre.

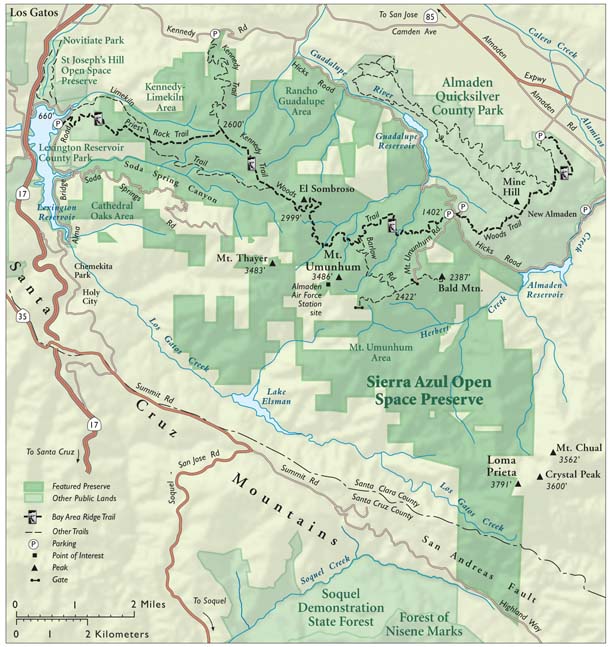

Sierra Azul is divided into four subunits, only two of which are currently open to the public. The more popular Kennedy-Limekiln Area abuts Lexington Reservoir County Park to the northwest, and can also be accessed from Kennedy Road in Los Gatos. A section of the Bay Area Ridge Trail connects that area with the Mount Umunhum Area, the district’s southernmost property, accessible from Hicks Road.

Mount Umunhum gets its name from the Ohlone word for hummingbird, or resting place of hummingbirds, but for decades the most obvious summit sight has been the six-story concrete blockhouse known as “the monolith” or “the cube.” A Cold War-era radar antenna once sat atop the cube, and from 1957 to 1980 Almaden Air Force Station personnel scanned 200 miles out to sea for Soviet bombers as part of the North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) civil defense infrastructure. Technological advances made such radar sites obsolete, and now the base that housed about a hundred military residents is a ghost town of dozens of structures, including an officers’ club, a two-lane bowling alley, and a swimming pool full of cattails.

- Like coyotes, bobcats do well at both Sierra Azul and many smaller preserves. Photo by Matt Knoth.

When the district purchased the summit parcel from the Air Force in 1986, it inherited a public safety headache–one with a humdinger 360-degree view and incredible potential, still unrealized. The Army Corps of Engineers is responsible for cleaning up toxics such as asbestos, lead-based paint, and solvents, a step the district estimates will cost $11 million. Then there are the unsafe structures, including the monolith itself, damaged in the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake. So the summit area remains off-limits to the public, which makes no one happy. Interlopers are subject to a $300 fine, and you can’t even walk up the road to the summit without trespassing on private property. Neighboring mountain folk have been known to wield guns and make citizen’s arrests, so prudent visitors stay on trails and respect no-trespassing signs.

- Mountain lions need much larger swaths of open space. Even Sierra Azul’s 17,000 acres may be insufficient, but new research aims to ensure the big cats can continue to move between this and other preserves. Photo by Frank S. Balthis.

The 1989 temblor that cracked the cube and rocked the Bay Area takes its name from the highest peak in the Santa Cruz Mountains, Loma Prieta, which lies just outside the preserve but is visible from the Bald Mountain Trail. (In Spanish, loma means knoll or hill; prieta means dark.) In that quake, the western side of the San Andreas Fault slid past the eastern side by about six feet, and the mountains shot up more than a foot.

It’s no coincidence that the highest peaks in the Santa Cruz Mountains occur in the Sierra Azul region, where the San Andreas, which runs just west of the preserve, makes a bend that increases uplift in an area already prone to upward thrusts. “A lot of the Santa Cruz Mountains are higher than they should be,” says naturalist and retired geologist Paul Heiple, “They’re eroding as fast as they can, but they’re still going up pretty fast.” That’s why you see sharp ridges, extremely deep valleys, and numerous landslides.

- In April, the rare Santa Clara red ribbons clarkia blooms along trail edges at Sierra Azul. Photo by Ron Wolf.

This region has long been recognized as good mountain lion habitat. Gato is Spanish for cat, and Los Gatos Creek and the adjacent town were not named for mousers. Sierra Azul not only offers habitat for individual mountain lions; it helps link habitats on the Peninsula with those to the south and east, linkages the big cats need to survive.

On the San Francisco Peninsula, district preserves and other protected lands offer good habitat connectivity for smaller animals such as coyotes and bobcats. Sierra Azul is prime territory both for those mammals and for mountain lions, but research suggests the whole Santa Cruz Mountain range doesn’t have enough wild habitat to support a self-sustaining puma population over the long term. Small, isolated populations face greater risks of dying out from disease, inbreeding, and natural disasters. It’s the dispersal of young mountain lions between neighboring regions that helps keep populations healthy.

- Anna’s hummingbirds notice the big berry manzanitas’ flowers and sometimes fight over prime stands. Photo by Rebecca Jackrel.

Just north of Sierra Azul, State Highway 17 cuts through the Santa Cruz Mountains between Los Gatos and Santa Cruz, presenting a formidable barrier to many animals moving up or down from the Peninsula. Last fall the district began funding a five-year research project to gather baseline information on how wildlife gets over or under the road. Strategically placed camera traps will document critter use of culverts and bridges. Road kill analysis can also be useful. In a separate effort also just getting started, researchers working on the Bay Area Puma Project will use sophisticated collars not only to track the cats’ travels, but also to begin to distinguish better habitats, as well as road crossings. Managers gather such information so that Caltrans can design road improvements that accommodate wildlife connectivity.

Keeping Highway 17 crossable ensures Peninsula habitats stay linked to Sierra Azul, but the cats also need passage south across the Pajaro Valley to the Gabilan Range and east across Coyote Valley to the Diablo Range (see our article Coyote Valley Crossings for more on an ongoing study of wildlife crossings in the Coyote Valley).

Plants also make unusual connections in Sierra Azul, where some reach the edges of their ranges and create unique assemblages. “This is the north/south divide of the Santa Cruz Mountains,” says frequent visitor Kevin Bryant, president of the Santa Clara Valley chapter of the California Native Plant Society. It’s higher, hotter, and drier here than on the Peninsula and looks more like the inner Coast Range to the east and south. For example, gray pine (also called foothill or ghost pine) is common in the foothills that ring the Central Valley, and is noticeable here but not farther up the Peninsula.

- Big berry manzanita, common here, grows no farther west or north in the Santa Cruz Mountains. Look for its flowers in winter, when few other plants are in bloom. Photo by Tom Cochrane.

Big berry manzanita is another example; it grows no farther west or north in the Santa Cruz Mountains. In winter, when the manzanita is in bloom, territorial hummingbirds often defend stands of it. “Hiking through Sierra Azul at that time, you’ll see the hummingbird wars going on,” Bryant says. Look underneath the manzanita for the maroon Indian warrior, a root hemi-parasite. Also in winter, look for blooming gooseberries and local chaparral currants that have unusually deep-colored flowers.

Most trails take you back and forth between chaparral and oak-bay woodlands. Another mostly inland flower, Brewer’s clarkia, blooms here in woodland openings in April. Look for the rare Santa Clara red ribbons clarkia along trail edges about then, too.

- In winter, look for the deep red blooms of Indian warrior under manzanita. Indian warrior is a hemiparasite that draws some of its sustenance from the roots of other plants. Photo by Kathy Korbholz.

California nutmeg also grows in the woodlands. Not related to culinary nutmeg, this tree is in the yew family and at first glance may look like a redwood– but with pointy hard needles. It has a fairly extensive range (the northern and central Coast Range and western Sierras) but you never see a lot of it. It’s also very slow growing. “If you see one that’s two feet in diameter, it’s been there hundreds of years,” Bryant says.

Along the Woods Trail, keep an eye open for the rock wall coated with plants in the stonecrop family, species of Dudleya and Sedum. You don’t have to key out what you’re seeing to enjoy the multitude of small plants with fleshy, water-storing leaves.

“It’s just a fantastically diverse place ecologically,” Freeman says. The district conducted a complete resource inventory before embarking on planning, so it’s well equipped to protect sensitive habitats even as it increases public access. The 30-year master plan remains officially a draft of recommendations until the district’s board of directors approves it, scheduled for fall 2009, after a few more hearings. The next public event is an informal open house this spring (2009).

The Rancho de Guadalupe Area, near Almaden Quicksilver County Park, is likely to open up in the first five years of the plan. “We’re really excited about that. It’s a beautiful area of Sierra Azul,” says Ana Ruiz, senior planner for the district. Rancho de Guadalupe is expected to be popular with hikers and equestrians, and the district hopes to remove fish barriers to improve steelhead spawning and possibly reintroduce the California red-legged frog to Cherry Springs Pond. The district might also open the southern Cathedral Oaks Area to the public, but north Cathedral Oaks will remain closed due to intervening private property.

- Map by Ben Pease.

And, of course, there’s the summit of Mount Umunhum. The district recently hired a lobbyist to press for Department of Defense funding of the cleanup. “The master plan we’re working on will help galvanize public support for the cleanup and I think it will get the ball rolling faster,” Freeman says. “It’s an opportunity for residents of the South Bay to have their own Mount Tamalpais or their own Mount Diablo.”

People who have been up to the high peaks and ridges in the Blue Range remark on the sensation of feeling a cool, moist ocean breeze caress one cheek, followed by a hot, dry inland gust on the other. But it will be years before visitors can look down from Mount Umunhum, as well as up at it.

Meanwhile, Sierra Azul still protects its big cats, rare plants, and other wild and wonderful treasures, and its trails beckon you to explore and make connections of your own.

Getting there: You can get to the Kennedy-Limekiln Area from Highway 17, and to the Mount Umunhum Area from Highway 85. Visit the district’s website (www.openspace.org) for detailed directions.

For more on the master planning process, go to www.openspace.org/plans_projects and click on the Sierra Azul/Bear Creek link.

.jpg)