ichard Neidhardt can easily name his favorite California condor. She’s No. 550 in the condor studbook, a small-statured female who has—remarkably, given all the obstacles—turned six this year, the age of sexual maturity in females. “I’m crossing my fingers I’ll have another grandchild,” jokes Neidhardt, a retired construction estimator from Point Richmond, who already has four of the human kind.

In 2010, he first spotted No. 550, or rather her benefactor, while hiking among the high peaks of Pinnacles National Monument—recently redesignated as a national park—an hour south of Gilroy. She was a pipping egg at that time, ready to hatch, in a padded box strapped to the body of a member of the California condor crew who was rappelling down a cliff face. “She was the one who started it all for me,” recalls Neidhardt, who has since become a ringleader in recruiting volunteers to the park service’s condor program and is raising thousands of dollars for the recovery work through the nonprofit Pinnacles Partnership, a “friends of the park” group.

California condors need all the help they can get. Saved from the brink of extinction with a controversial plan in the mid-1980s to bring the remaining nine wild individuals into a captive breeding program, condors have become one of the most highly managed endangered species in history. Wildlife officials, with the help of several zoos, have been steadily growing the population. And in 1992 they began releasing captive-bred fledglings into the wild in an effort to reestablish these massive scavengers—the largest soaring birds on the continent—in a core part of their home range, stretching from Pinnacles to the Big Sur coast. Condors once patrolled the skies as far north as British Columbia, but Pinnacles now marks their northernmost breeding area. Other condor populations have been reestablished to the south in Southern California, Baja California, and Arizona.

The condors have fared better than expected, with an estimated 80 wild individuals in the Central California flock in 2016, but their recovery has hinged on a highly orchestrated effort to keep them on the upswing. When Neidhardt first saw No. 550, suspended in midair near a cliff face, she was a captive-bred foster egg headed to the nest of first-time parents who’d failed at producing a viable egg earlier in the season. With a whole lot of human help, she became the first condor chick to hatch at Pinnacles in a century.

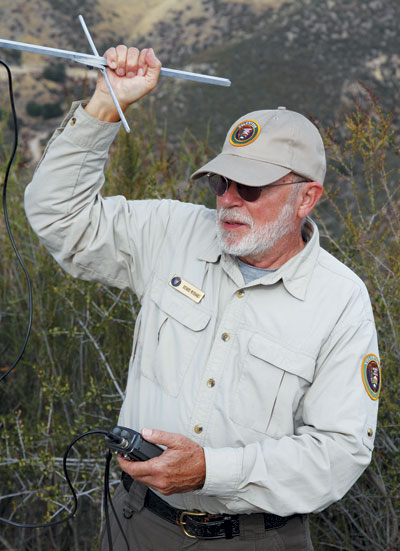

Now he occasionally spots her as an adult bird in his volunteer work as a condor tracker at the park, though usually not by sight. Every bird is outfitted with a radio transmitter or GPS device and marked with a unique number. The park service, in collaboration with the Ventana Wildlife Society, which covers the Big Sur side of the range, aims to get a signal or a visual on every bird at least every three days. The goal is to track the birds’ locations, and be able to swoop in to help an ailing bird or retrieve it for a necropsy if it dies.

Doing so requires a dedicated team of volunteer condor trackers—currently 12 in all—to hike the high peaks or drive through the privately owned ranchland outside the park. The birds rarely stay put for long in their determined search for carrion—from small lizards to large mammals. “We’ve definitely come to rely on volunteers,” says Rachel Wolstenholme, Pinnacles’ condor program manager and a national park employee. “There would be a lot less done if we didn’t have them.”

On a hot July morning, we hike up the park’s Condor Gulch Trail to a lookout informally called Doodle & Dottie, a rocky peak studded with chamise and featuring a view of a barren ridge in one direction and a parched valley of ranchlands in the other. Wolstenholme doesn’t get out on the trail much, relying on volunteers to do most of the condor tracking work, but on this day she is demonstrating how it all works. “You have about a 50-50 chance of seeing a condor,” she warns, removing a radio receiver and antenna from her daypack. Though turkey vultures are ever-present, when it comes to tracking condors, you’re most likely to hear one via its transmitter.

Beep, beep, beep. Wolstenholme has waved the antenna to a spot where the receiver dial picks up the frequency of No. 525, a female born in 2009. “Each bird is its own radio station,” she tells me. She loses the signal before picking it up again. “It means she’s flying up into range and then out. She could be close, just behind those hills.”

Just as important as finding a bird’s signal is not finding it, or even worse, picking up the transmitter’s rapidly beeping signal that warns of inactivity, sort of like a patient in distress on an EKG. We get one of those for No. 463, but Wolstenholme thinks it’s probably a transmitter attached to a tail feather that fell off, though she makes a note to double-check the records back at the office.

Although the condor population faces a number of stressors—from urbanization and power lines to ravens preying on the young—by far the greatest threat to their existence is lead poisoning, caused by lead ammunition fragments in the carrion they eat when hunters or ranchers leave behind animal remains. In California, it’s illegal to hunt with lead bullets within the condor’s range for most types of prey, and by 2019 that restriction will apply statewide to all hunting and wildlife pest management. But condors cover a vast territory—flying up to 150 miles in a day—which makes enforcement of the law tricky, particularly in the enormous private ranchlands surrounding the park. So the park service and other condor advocacy groups have focused on public education to turn the tide of tradition and switch people to lead-free bullets.

“Ranchers feel like they’re under the burden of so many regulations, so just the fact that there is a lead ban in our area, people are like ‘Holy crap, this is a whole other thing government is telling me I can’t do on my property,’” says Karminder Brown, who heads the San Benito Working Landscapes group for the Pinnacles Partnership.

Though the public education effort seems to be helping—through outreach and raffles for non-lead ammunition—condors are still dying from lead poisoning, and many require chelation therapy to reduce elevated levels of lead. Blood tests done annually on every captured bird indicate the majority have elevated levels of lead. “We are managing a population of birds with chronic lead poisoning,” Wolstenholme says.

Toxicology research out of UC Santa Cruz is looking at the physiological and behavioral impacts of sublethal doses of lead in condors by measuring changes in the birds’ corticosterone levels, the avian equivalent of the human stress hormone cortisol. The studies, made possible by all the data collected by tracking and trapping birds over the years, should help scientists get a better handle on condor survival and has implications for other bird species, such as eagles and hawks, similarly affected by lead poisoning. “These condors are giving scientists a great gift in that we’re able to learn from them about the impacts of lead poisoning on avian species,” says Zeka Kuspa, a UCSC doctoral student who is leading the research.

Despite the challenges, the condors are showing remarkable resilience. By the end of 2015, the condor population in California, 155 birds strong, had exceeded the federal recovery goal for California of 150 free-flying birds in a wild, spatially distinct population, though it will take more good years for scientists to conclude that the birds are self-sustaining. The state’s flocks are intermixing and reaching new areas, with one juvenile spotted by a motion-activated wildlife camera on a private forested property near the San Mateo coast in 2014, the first condor sighting in the county since 1904. To Neidhardt, one fact stands out: Last year for the first time in the recovery effort the number of chicks born in the wild in Central California exceeded condor deaths. “That’s a huge victory. What that means is that there are enough breeding pairs out there in the wild that they are able to start replacing themselves,” he says.

If the trajectory continues and people stop using lead ammunition, Wolstenholme reckons that in about five to 10 years the population will have grown so large that intensive monitoring of individual birds will no longer be possible—a problem she welcomes. “There’s this feeling, why can’t you just leave the birds alone? My goal is that ultimately we don’t need the tags, the transmitters, the capture and handle. These are wild birds that should eventually be able to live their lives without interference.”

-300x226.jpg)