Kunisha Fernandez, her husband Steven Fitch, and their four children had spent five years in Las Vegas when, last spring, Fernandez saw a YouTube video of a family camping full-time: “A day in our life! Family living in a tent.” Fernandez found it captivating—four girls and their dad walking on the beach; dinner cooked on a campfire overlooking the ocean; life under starry skies.

Fernandez watched another video like it and then another, over and over again, like a playlist, and she thought about how her family had never gone camping together. That night, she shared it with Fitch. “Wouldn’t it be cool if we did this?” she asked.

Fitch agreed. The two had met in San Diego, where they both grew up. Fernandez, 31, worked remotely for a company that retrieved medical records, while Fitch, 33, worked as a mover, but they struggled to find a two-bedroom apartment for less than $2,000 a month. In 2016, they moved to Las Vegas, where they heard housing was cheaper, but after a few years, rents started going up in Las Vegas, too, and Fernandez found the heat excruciating.

It was a system neither Fernandez nor Fitch wanted to be a part of any longer. “Why do I have to pay so much just to have somewhere to live?” Fitch thought. “What kind of life is that?”

In the YouTube video, they glimpsed an alternative — a way to get out. So they showed it to their kids: Caliyah, 9, Prince’Ellijah, 5, Prince’JahZiah, 1 and a half, and Amoriah, 4 months old at the time. “How would you like to live outside full-time?” they asked.

Fernandez and Fitch were prone to spontaneity, and a week later, they had sold most of their possessions and traded in their car for a used minivan. They bought two large floor tents, six cots, camping chairs, a battery-powered showerhead, solar lights, a fold-up table, and a cooler. On June 5, 2021, they piled everything into their minivan and drove away from Las Vegas for good, heading towards Lake Mead.

They drove east to Utah, and then to western Colorado, into the Elk Mountains. A few miles from the town of Carbondale, down a rugged dirt road, they found a free primitive camping area—firepits, no amenities—on Bureau of Land Management (BLM) land. They set up camp on a large flat spot near a creek shaded by pine trees.

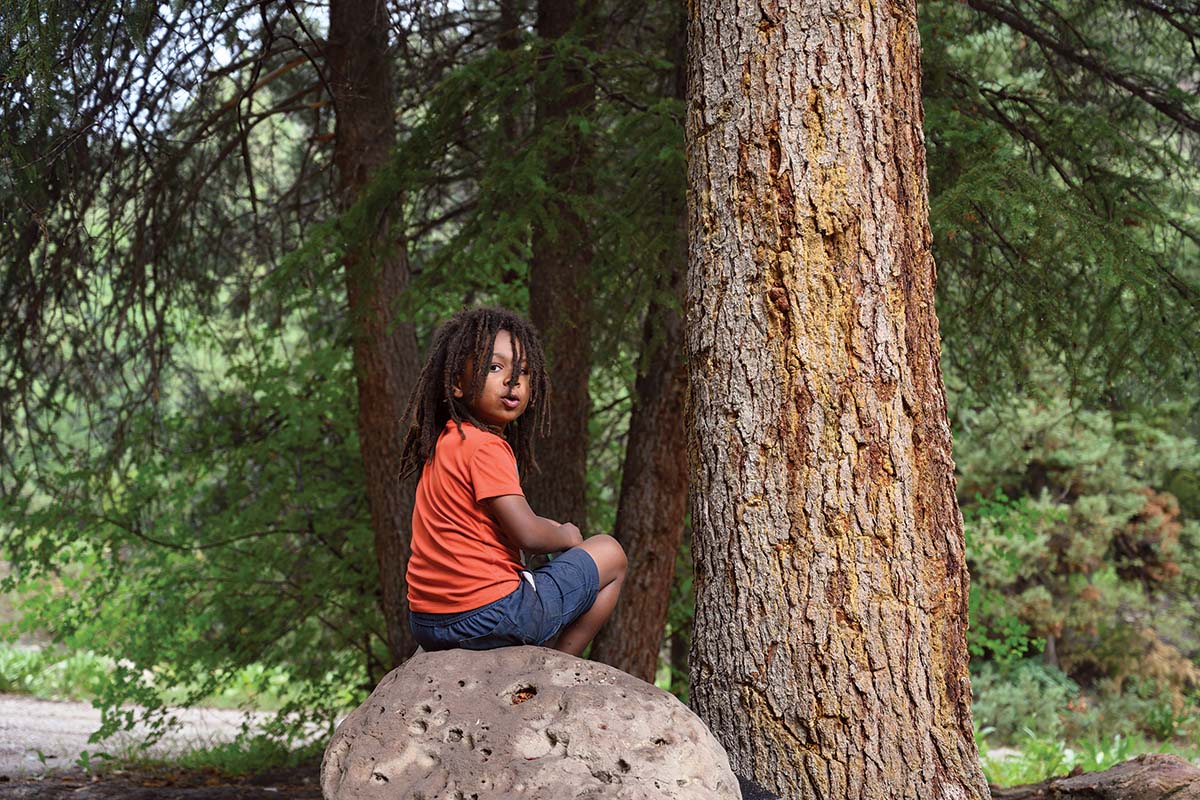

Fernandez was surprised by how much the kids loved their new life in the forest. Their clothes were often dirty and they got mosquito bites on their faces, but they could run around in the woods, picking up pine cones, collecting leaves, learning the sound a woodpecker makes and how water flows in a river. Fernandez saw that instead of buying them toys, she was giving them experiences—and she liked that.

Fernandez, Fitch, and their kids are part of a growing contingent of Americans living nomadically in vans, RVs, and tents on U.S. public land. Most of those approximately 625 million acres are managed by federal agencies, including the BLM, the Forest Service, the National Park Service, and the Fish and Wildlife Service. Many tribal, state, and municipal agencies also allow camping on their public lands. Most nomads opt out of established fee-based campgrounds in favor of free dispersed camping—also known as primitive camping, boondocking, and dry camping—a time-honored tradition across the West that often involves driving up a forest access road to a pullout without toilets, running water, or other amenities. The rules vary across the different land-management agencies, but most allow campers to spend 14 days in one location. For some nomads, camping is a lifestyle choice, popularized by Instagram hashtags and the possibilities of remote work. For others, though, it’s a necessity owing to hardships such as lost jobs, mental illness, and housing costs.

Longtime vehicle-dweller Bob Wells, the creator of CheapRVLiving.com and a guru for nomads on tight budgets, sees nomadism as a response to deeper societal crises. There’s no way to track the exact number of nomads, but one indicator is Wells’ website, which has surged in popularity since the 2008 recession, when 10 million Americans lost their homes. Wells was inundated with letters and emails from people saying “I can’t live anymore”—something that’s continued as the country’s affordable housing shortage has worsened.

If the recession shook the foundation of American societal norms—notably the belief that if you worked hard and saved money, you could have a stable middle-class life—the pandemic jackhammered the rest, says Wells, 66, who recently played himself in the Oscar-winning film Nomadland. “I think things are going to be very different going forward,” he told me, noting the “flood of people leaving California because it’s so expensive and crowded.” And climate change, Wells believes, will only accelerate that trend. With wildfires and extreme temperatures, he says, “we’re going to be a planet on the move.”

In January 2011, Wells held a gathering in the desert outside Quartzsite, Arizona, halfway between Los Angeles and Phoenix, for an event he dubbed the “Rubber Tramp Rendezvous.” That first year, 45 vehicles showed up. By 2019, an estimated 10,000 were there. One of Wells’ most popular YouTube videos, “Living in a Car on $800 a Month,” now has over 4 million views.

Whatever the motive, the growing presence of campers on public land is having an impact, from trampled vegetation and improperly buried human waste to trash piles deep in the woods. The cleanup costs incurred by non-recreational campers in hot spots like Oregon’s Willamette National Forest were as high as $250,000 in 2018. Those biophysical impacts—as well as the growing threat of wildfires—spurred land managers to restrict or shut down dispersed camping in places like Colorado’s Arapaho Roosevelt National Forest near Boulder, the Tahoe National Forest in California, and the BLM’s Carson City District outside Reno, Nevada. As increasing numbers turn to the West’s public lands for solace and escape, the conflicts around dispersed camping are raising difficult questions over what exactly it means to camp, and what—and who—the public lands are for.

Even before the pandemic, land managers noticed a growing number of non-recreational campers. A 2015 study found that Forest Service law enforcement officers and other officials in many parts of the U.S. were encountering a steady flow of people using public lands as a temporary residence. The largest share were transient retirees, followed by displaced families and homeless individuals. Nearly half the 290 officers surveyed reported that encounters with non-recreational campers had increased over time. Officers in the Rocky Mountain Region and the Southwestern Region, as well as California, encountered non-recreational campers most often; more than half the officers in both regions reported coming across such campers at least once a week, as did 42 percent of officers in California.

The findings make sense in the context of America’s housing crisis and rising homeless population, says Lee Cerveny, a research social scientist with the Forest Service’s Pacific Northwest Research Station, which spearheaded the 2015 study.

Western states have some of the highest rates of homelessness, according to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s 2020 Homeless Assessment Report. California tops the list, with 161,548 people experiencing homelessness—28 percent of the entire country’s unhoused population. Mental health problems, addiction, childhood trauma, interaction with the criminal justice system, and poverty all play a part in whether someone becomes homeless. But the main reason? The person can no longer afford rent.

In the San Francisco Bay Area, for instance, the median price of a home was over $1.3 million in 2021 and the median rent as of August was $2,795 for a one-bedroom apartment. Meanwhile, California’s homeless population rose 16 percent between 2007 and 2020. When the pandemic hit, the state rental market tightened and people lost jobs and income. In Marin County, the number of people living in cars and RVs nearly doubled between 2019 and 2020. During the same period, Sonoma County—where a series of devastating wildfires starting in 2017 has already pushed more people into homelessness—saw a 42 percent increase in homelessness among older adults, as well as an increasing number of people living in vehicles. “It’s become a strategy or alternative form of shelter,” says Jennielynn Holmes, chief programs officer for the Catholic Charities of the Diocese of Santa Rosa, a nonprofit that assists the unhoused. “People purchase a run-down vehicle and then park it somewhere and live in it for a number of years,” she adds, often on city streets or in encampments on the outskirts of town. With dispersed camping banned in most urban areas, other long-term vehicle dwellers have left California entirely, living on the road in states where gasoline and other necessities are cheaper.

For Cerveny, the survey is illuminating in less tangible ways, too: All the websites and social media promoting nomadic lifestyles seem to ignore the more troubling social, economic, and environmental conditions behind the trend. “What does it say about our society,” she asks, “that so many people are feeling like they don’t have options for living except to move around in an RV or a camper?”

The last time Dirk Addis paid rent was May 2002. A month later, he moved from San Diego to Mammoth Lakes, a popular mountain town in the Eastern Sierra, to work in a gear shop. Even then, the town had limited affordable housing options, so Addis decided to try living out of his van for the summer in the Inyo National Forest, which encompasses all but four of the town’s 24 square miles.

When I met Addis, 54, one afternoon for coffee, he wanted me to know that he is not homeless—nor does he even really “live” in his vehicle.

“I live on planet Earth,” he said. “I just happen to sleep in my van during inclement bouts of weather. Otherwise, I’m sleeping outside under the stars.” Addis averages 200 nights a year sleeping that way. His cousin calls it NUTS: nights under the stars.

But for all its romantic connotations, Addis’s lifestyle was born out of a housing crisis. Like Fitch and Fernandez, Addis is what he calls “homeless by design”—partly because the local housing alternatives are unappealing at best and nonexistent at worst.

As in most ski towns, the majority of Mammoth’s homeowners do not live in Mammoth. They live in Southern California and come to ski on weekends or spend a few weeks during the summer. In the hills around Mammoth, empty lots sell for over $1 million, and new five- to seven-bedroom mansions go for upwards of $5 million. Most of the more affordable housing is in a series of densely packed condominiums and small A-frames built in the ’60s and ’70s near the center of town. But with Airbnb’s arrival 10 years ago, many of the second-home owners who previously rented their condos to locals switched to nightly rentals instead, exacerbating an already strained housing market. According to a report from Mammoth Lakes Inc., a local housing nonprofit, more than half of Mammoth Lakes’ households cannot afford market rate rents in the town.

Addis, who currently works as a maintenance man for a condo complex, is blunt about Airbnb: “It has fucked ski towns,” he says.

Addis quickly realized that he would have to work at least two, probably three jobs and spend at least half of his earnings on rent—most likely a tiny studio apartment or a condo with multiple roommates.

“What the hell!” he says. “No!”

So Addis stayed in his van that winter. Then another winter, and another, moving every 14 days to a new site to stay within the laws. He was not the only one who saw the forest as Mammoth’s best available housing option. In the early 2000s when Addis began living in his van, he estimates, there were at most 20 people living in the forest during the summers and five who did it year-round like him. Now, he says, there are roughly 100 people in the summer and probably about 30 during the winter, when it can snow five feet at a time.

When Stacy Corless, the District 5 supervisor for Mono County, moved to Mammoth more than 20 years ago, a longtime local named Hal lived in the woods year-round. Other Mammoth residents thought he was quirky and rugged, but as more people took up residence in the forest, Corless saw people’s opinion about forest living change.

“Somehow that was OK, when it was just this one individual,” Corless told me. “Now it’s less palatable to residents.” She recites the complaints she’s heard from constituents in recent years—trash, human waste, illegal campfires.

During the summer of 2020, rising tensions over dispersed camping exploded when recreational campers arrived in the Eastern Sierra in unprecedented numbers, eager to escape their pandemic-induced confinement. The surge of visitors combined with the unhoused put dispersed camping in the city’s crosshairs.

On Labor Day weekend, the Scenic Loop, a road that circles through Forest Service land just outside of Mammoth, was packed with RVs and wall-to-wall campers. “It looked like a homeless encampment,” Corless says. That Friday evening, the Creek Fire started near Shaver Lake, roughly 40 miles away. Mammoth residents watched as an apocalyptic-looking smoke cloud formed in the sky above them while the nearby forest grew more and more crowded with weekend dispersed campers. Corless’s phone started ringing. “You’ve got to do something,” people said. “There are so many people on the Scenic Loop—get the sheriff out there!”

For Corless and other local officials, the chaos of last summer was a jolt to take action. The general feeling was “we gotta figure this out,” she says.

Last winter, Corless and other Mono County officials joined their counterparts from neighboring Inyo County on a 65-person Zoom call. Together they came up with a plan to deal with the recreational weekend visitors. The result was a multipronged approach: a free app showing the entire Eastern Sierra with clearly marked boundaries indicating where dispersed camping was allowed and where it was not; an outreach campaign called “Camp Like a Pro” to educate visitors about the rules of responsible dispersed camping; volunteer stewards to remove fire rings and talk to campers; new portable toilets and dumpsters in popular areas; and a more consistent enforcement strategy among the various law enforcement agencies.

Despite those efforts, the previous summer’s surge put an unwelcome spotlight on people living in the forest around Mammoth. As the summer of 2021 approached, some Mammoth residents began calling for an outright ban on dispersed camping in the Eastern Sierra for visitors and locals like Addis alike. In late April, Chris Leonard, a teacher at Mammoth High School and a fly-fishing guide who’s lived in Mammoth for 17 years, penned an op-ed in the local newspaper after counting 10 RVs and vans camped in the forest east of town.

“This is a major issue,” he wrote, noting that in summer 2020, Inyo National Forest was “overrun” with dispersed campers who might leave behind trash, drive through areas not meant for vehicles, harm or disrupt wildlife, and create major forest fires. Already, the Mammoth Lakes Fire Department had been called to the forest twice in the previous two weeks that summer to put out abandoned campfires.

“The threat is huge,” he added. “It is also very, very unsightly.”

One afternoon in Mammoth, I met Leonard, who has a small fish tattoo on the left side of his neck and a direct, no-nonsense vibe. When I asked him about the op-ed, he acknowledged that he had been too extreme. “It was not the correct approach,” he said. “I realize that now.”

Leonard told me that the new efforts to manage dispersed campers, plus a decrease in visitors compared to last summer, had helped soften his views. Still, he considers the RVs, in particular, an eyesore. He offered to drive me out to a popular dispersed camping area—a wide basin east of town near Hot Creek, one of his favorite fishing spots.

We stopped at a pullout overlooking the creek. Leonard pointed to a group of RVs parked off on a hillside. “So, it’s an unofficial RV campground,” he said. “Is it right, or is it wrong? I don’t have the answer to that question. I’d prefer they’re not there, but they’re there.”

Later, he admitted he has the luxury of saying all this as a homeowner in Mammoth. “It’s easy for me to be up on the pedestal being like, ‘Get the fuck out of the forest,‘when I can go home to my house every night,” he said.

Recently, Mono County voted to ban overnight camping in the parking lots of county parks and on paved roads. Corless worries the ordinance will push people living in the forest farther from town, instead of solving the problem. Mammoth, like many mountain towns, has not protected its existing low-cost housing or built additional units to the extent necessary for an affordable community housing market. A few years ago, Mammoth purchased land in the town’s center for more affordable housing, but those units won’t be ready for another couple of years. “You can’t catch up from 40 years of policy that didn’t address housing needs in a year,” Corless says.

For Fitch and Fernandez, nomad life turned out to be more challenging than in the videos. A week after they arrived at their Colorado site, they piled into the minivan for a day trip to some nearby hot springs. When Fitch pressed on the gas, the car didn’t move—the transmission had blown. Their campsite had no cell service, so Fernandez walked partway into town to call AAA, but their car was too far from a main road for a tow truck.

Without money for a new car, they were effectively stranded. This was not something Fernandez anticipated when she dreamed of their new life, but she told herself that everything happens for a reason.

Instead of moving around as planned, they stayed where they were. Fitch found work as a mover in Carbondale so they could afford to buy a new car. For the first few days, he commuted the 18 miles round-trip from their campsite into town using a bike someone gave him—until his boss discovered he didn’t have a car and loaned him a moped. Meanwhile, Fernandez cared for the kids back at their campsite.

One afternoon, I visited. Fernandez emerged from the tent looking tired—Amoriah, normally an easy baby, had been crying all morning. Fernandez popped a marshmallow into her mouth and handed Amoriah to Fitch. Together we walked down to the creek, which was the color of chocolate milk after the recent monsoon. The storms had surprised them. “People told us Colorado was dry,” Fernandez said.

The last week of July it rained every day. The rutted road down to the campsite became so slick with goopy mud that Fitch couldn’t get to work. He lost his job. A few days later, a BLM law enforcement officer told them they had stayed there too long and had to leave. Fernandez, who was alone with the kids, tried to explain their situation, but it didn’t matter. The rules were the rules.

The next day was Fitch’s 33rd birthday, but there was no time to celebrate; they had to figure out their next move. It felt like they were getting evicted, Fitch said. “We were getting kicked out with no transportation and had no place to go.”

I asked if the setbacks had made them reconsider their decision to live in the forest. If anything, Fernandez said, it had motivated them to keep going, to keep experiencing these wild places. This was land that belonged to them, but where they rarely saw other Black families like theirs. The situation reminded Fitch of a Lauryn Hill song he likes called “Get Out”: “I get out,” Hill sings; “I don’t respect your system/I won’t protect your system.”

A day later, the family rented a U-Haul and were moving to a new location. Next time, Fitch said, they would make their own campsite deeper in the forest, somewhere no one could find them.

This story was made in partnership with High Country News.