In a world where money talks, as they say, nature has been at a distinct disadvantage. How do you put a price tag on the existence of a species, or the workings of a watershed, or the presence of a forest?

And yet it’s obvious that nature has value and can do important things for us, other than provide resources to be exploited. For years, conservationists in the public policy arena have tried to make the philosophical argument that undeveloped nature is an asset, economic as well as spiritual and recreational. That is, a tree that isn’t logged provides services such as erosion control, air filtering, and acts as a carbon sink, all of which have an economic value, but just not one that we typically measure. Now, three Bay Area counties —Santa Clara, Sonoma and Santa Cruz — have found a way to put these values of nature onto a balance sheet.

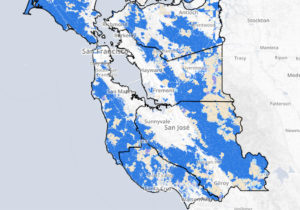

Santa Clara Valley Open Space Authority was the first to go in the collaborative three-county effort, releasing a report earlier this summer called “Healthy Lands & Healthy Economies: Nature’s Value in Santa Clara County,” that tallies up its “natural capital asset value” to as high as $386 billion. The other two counties are scheduled to release their reports in October and November. That $386 billion represents an (incomplete) total of all the things the natural landscape does for the people of Santa Clara County, including flood control, groundwater recharge, soil retention, natural disaster mitigation, and support of agriculture and recreation, to name a few.

“Yes, nature is a nice thing to have,” says Andrea Mackenzie, general manager of the Santa Clara Valley Open Space Authority. “But this is about all the other things that nature brings that right now are not figuring into the decision-making process, and certainly not on the balance sheet.”

The numbers are broken down by habitat type on private and public lands throughout the county. The 588 acres of deciduous forest in Santa Clara County have an estimated worth of between $1 million and $3.8 million, while the 3,272 acres of tidal wetlands (called “estuarine emergent wetlands,” characterized by salt water and aquatic plants) amount to between $45.5 million and $187 million. The 160,835 acres of grasslands proudly hold their own at between $529 million and $1 billion for providing such services as soil retention, pollination and climate stability.

To produce the reports, the three counties hired the Tacoma, Wash.-based ecosystem services firm Earth Economics, which bills itself as having the largest, most comprehensive database of published, peer-reviewed primary valuation studies in the world. The firm based its calculations on valuation studies done of similar habitats in areas with similar demographics and ecological characteristics, both in the US and around the world.

Fuzzy Math?

It may sound a little like fuzzy math, and to be sure, Mackenzie and the other county leaders admit the limitations of the so-called “benefit transfer methodology.” For one, the valuation studies, for the most part, don’t take place locally — that would be too cumbersome and expensive. At least a hundred primary studies were used to make the report, costing upwards of $100,000 each in research funding. But officials say the results are a starting point, and are certainly more accurate than nature being considered a “free” resource — as it has traditionally been viewed. Or worse, as a “cost,” when it comes to raising money to buy open space.

Each county is supplementing the primary studies with their own localized valuation study, which will go into Earth Economics’ database. In Santa Clara County, the study centered on a return on investment calculation for the 352-acre Coyote Valley Open Space Preserve, a mixed oak woodland and grassland ecosystem at the eastern base of the Santa Cruz Mountains that was purchased in 2010. By 2020, the preserve will have returned $3.41 in investment for every dollar spent, and by 2040 the return jumps to $6.23, according to the report. The property’s value includes recreational benefits, grazing revenue and ecosystem services.

Jim Robins is the consultant who coordinated the “Healthy Lands and Healthy Economies” initiative, which was funded by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the S.D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, and the State Coastal Conservancy. Robins says the counties banded together after seeing the field of “ecosystem services” take off elsewhere in the last few years with some high-profile players. “For years people have been talking about ecosystem services, and that these things are so important and we need to figure out how to make that argument,” said Robins. “We’ve been waiting for the science to catch up to common sense.”

Notably, in 2013 the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), following an Earth Economic analysis, began including ecosystem service valuation in its analysis of hazard mitigation. Specifically, the agency is accounting for the value of floodplain lands in reducing flood risk. And the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission commissioned Earth Economics to do an economic impact study of the 2013 Rim Fire on natural lands, which put the damage as high as $800 million, much of it in lost carbon storage.

For these Bay Area counties, the ecosystem services reports are a way to tap into bigger funding pools that could be put towards conservation. Mackenzie says that large infrastructure projects — be it a dam, a highway, or a new development — often “throw a little money here and there” for mitigation or for green projects to gain public support. But natural assets, and the services they provide, “are being left out of the equation by major funding sources,” she says, and now it’s time for them to be given their financial due. “

Drought May Help

California’s ongoing severe drought may help make the case for valuing natural lands. Local water supplies, including underground aquifers, are now in great demand, and all three counties are trying to parlay their reports into new protections for lands that are critical for recharging groundwater supplies.

Sonoma, for example, is doing a localized study of the role that natural land conservation has played in ensuring water quality and supply to the county’s 600,000 people, and comparing those investments to the theoretical cost of constructing new infrastructure to capture and filter that same water.

“Basically that would be of service in telling our taxpayers, who contribute a quarter-cent sales tax, what they get for their money,” says Karen Gaffney, conservation planning manager for the Sonoma County Agricultural Preservation and Open Space District. “It may actually be more cost effective to invest in conservation … and if we’re going to rely on conservation to provide these benefits, we probably need to increase the scale of it.”

Santa Cruz County, which relies almost entirely on groundwater to supply some of the most productive agricultural fields in the state, did a similar localized study for its report. It looked at a two-acre basin that collects water from 120 acres of land, and found that it recharges the aquifer at a rate of around 90 acre feet of water per year. Creating ten such basins in areas with suitable soils could recharge almost 1,000 acre feet of water, plus provide ancillary benefits of flood control, recreation, and bird habitat, says Sacha Lozano, program manager of the Santa Cruz Resource Conservation District. With the value of the land calculated, Santa Cruz County has identified suitable land for rainwater infiltration.

“We’ve developed a language that speaks more directly to investors that are not involved in the conservation world,” says Lozano. “It’s like a communications tool more than anything. It’s being able to bridge different worlds through the language of money.”

Dollars and Cents

The dollars-and-cents approach to conservation is not without its detractors. Some environmentalists believe the intrinsic value of nature should decidedly not be reduced to dollars and cents.

Then there are those on the other side of the spectrum who might balk at the assertion that the value of Santa Clara County’s natural assets ($386 billion) could be higher than the total asset value of all its residential and commercial real estate ($334 billion). “I could see how a factoid like that could be pretty galling to industry,” says Mackenzie.

Still, she said the reaction to the report has been largely positive.“We’re trying to do a good job of reaching out to unlikely partners,” she said. “We’ve been talking to members of the Silicon Valley Leadership Group — we did a presentation for their environmental committee — and for the most part there’s been an openness and receptivity to it, but they want to see the numbers to better understand the case being made.”

It’s not a coincidence that Santa Clara’s report was issued in advance of a November ballot initiative, which would double the amount of public funding for the open space authority from its parcel tax, resulting in $7.9 million annually for open space.

Mackenzie says some of these funds would be directed toward a new program to provide incentives to private landowners to protect the ecosystem services on their lands for a designated time period through a kind of conservation stewardship grant. Nothing like this has been done before at a regional level, she says.

It’s a different kind of tool than buying the land outright, or putting it under a permanent conservation easement, Mackenzie says.

“We have to have more tools in the toolbox,” she says. “You often hear private landowners say at meetings: ‘If you want me to protect the red legged frog, then pay me.’ We know the property is valuable, and we want to invest in that service and we will find the sweet spot for the landowner to make that happen. We’re trying to use these cutting edge tools and approaches.”

A copy of the Santa Clara report can be viewed here.

Alison Hawkes is the online editor of Bay Nature.