The dim trail lay like a rambling red shadow cast on the soft forest floor by the great redwoods and over-arching oaks. It seemed as if all local varieties of trees and vines had conspired to weave the leafy roof—maples, big madronos and laurels, and lofty tan-bark oaks, scaled and wrapped and interwound with wild grape and flaming poison oak. — Jack London, The Valley of the Moon, 1913

This autumn, nearly a century after the appearance of the author’s romantic farming novel, the poison oak still blazes along the trails at Jack London State Historic Park in Glen Ellen. This jewel of a park, dedicated to a writer known mainly for naturalistic adventure stories like The Call of the Wild, nestles on the slopes of 2,300-foot Sonoma Mountain in the aptly named Valley of the Moon—one local legend has it that “Sonoma” is an old Indian word for moon. In modern times the tanoaks have been devastated by sudden oak death—currently the park’s affected areas are under scrutiny by plant biologists from UC Davis and elsewhere—and the rich plant communities that produce the natural canopy have in many places been planted to domesticated vineyard. But thankfully, those vineyards lie outside the 1,400 acres of preserved parkland.

The oak-killing disease would certainly concern Jack London if he were alive today; he took his stewardship of the land seriously. But the city-born writer raised on the Oakland waterfront had nothing against vineyards. Ahead of his time, he consulted with the experts at a fledgling UC Davis campus and envisioned sustainable farming as the key to solving what he called “the great economic problems of the present age.” “I see my farm in terms of the world,” he asserted, “and I see the world in terms of my farm.” He let it be known that, given a choice, he would rather be remembered for his agricultural innovations than for his literary efforts. That he was prolific in both pursuits comes as a surprise to most first-time park visitors.

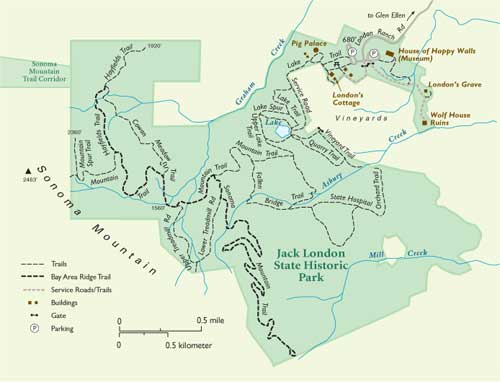

I worked for more than two decades at Jack London State Historic Park as a ranger leading tours and answering questions about London, who not only wrote and farmed, but sailed and traveled halfway around the world. Because of the park’s widely scattered physical landmarks—a dozen sites reached by a mile and a half of trail—most of the answers I gave helped people connect the basic historical dots: Start at the House of Happy Walls (classic old museum—all 51 published books on display), go to London’s grave (kidney failure), Wolf House ruins (burned by spontaneous combustion—oily rags), Ranch Cottage (new Jack London museum in waiting), Pig Palace (efficient, sanitary), trail to lake (no swimming), and finish near the summit of Sonoma Mountain (outside the park boundary—no trespassing, please).

- The shady forests below Sonoma Mountain drew Jack London tothis place. Though the old-growth redwoods here were logged before hearrived, Jack London State Park retains a great diversity of nativetrees, including sprawling oaks like this one. Photo by Gregory Hayes.

After a couple of hours touring the buildings, the discerning hiker concludes there must be more hidden treasure in the park than first meets the eye. Fifteen miles of trails include the moderately steep Mountain Trail to the park summit and the new gently graded Sonoma Ridge Trail, which offers excellent views of the valley. (The latter is part of the Bay Area Ridge Trail.) Most of the hidden treasures—the unadvertised, unlisted sites—have to do with natural rather than cultural history. That puts modern visitors in Jack London’s boots and brings them eye to eye with his vision of the place when he first visited in 1903, long before his fame caused it to be designated a state and national landmark in the 1960s.

Soon after his initial visit to the “Valley of the Moon,” London gushed about his prospective land buy in a letter to his publisher asking for an advance:

There are 130 acres in the place, and they are 130 acres of the most beautiful, primitive land to be found in California. There are great Redwoods on it . . . as fine and magnificent as any to be found anywhere outside the tourist groves. Also there are great firs, tanbark oaks, maples, live-oaks, white-oaks, black-oaks, madroño and manzanita galore. There are canyons, several streams of water, many springs . . . I have been riding all over these hills, looking for just such a place, and I must say that I have never seen anything like it.

As he stitched his ranch together out of six run-down farms and groves of second-growth redwoods, London had good reasons for his own personal return to the soil. An avowed socialist who had grown weary of city life, he was charmed by the serenity and natural beauty of the place—so much so that he named it Beauty Ranch. For a man who had traveled across the continent, explored the Klondike, and sailed the South Seas, that was quite a testimonial to one small North Bay valley: In all his travels he had not found “anything like it.”

London, who by 1906 was one of the highest-paid writers of his day, said of his move from Oakland to Glen Ellen that he wanted to put down an “anchor” on the side of Sonoma Mountain. For the self-proclaimed “Sailor on Horseback,” this took the form of an extravagant house-building project. In Wolf House, London envisioned an ancestral home, a refuge, workshop, place of celebration—after an impoverished, itinerant childhood, the only home he would ever call his own. Construction began in 1911, five years after he had witnessed and chronicled the catastrophic San Francisco earthquake and firestorm. The 15,000-square-foot house rose four stories, commanding a view of the Sonoma Valley, and contained 26 rooms and nine fireplaces, as well as modern conveniences such as hot water, heating, electric lighting, and refrigeration. London believed it to be both earthquake- and fireproof and hoped it would stand “a thousand years.”

- London works on the manuscript for his novel The Sea-Wolfat a stump table on his Sonoma ranch. During his short life, heauthored 51 books, from nautical adventures to romantic pastorals setin a landscape much like his ranch. Photo courtesy of California StateParks, 2006.

Tragically, on August 22, 1913, only a month before London and his wife, Charmian, were to move in, fire destroyed the home. “It was a very quick fire,” said a devastated London. “The walls are standing, and I shall rebuild.” But already suffering from poor health and disease probably contracted during his travels in the South Pacific, London never recovered from the blow. Three years later, he died of kidney failure at the age of 40, his reconstruction plans never realized.

The evocative ruins of Wolf House remain the single most popular attraction in the park today. It is, however, only one of many footprints London left behind on the land. After losing his dream house, he focused obsessively on perfecting his farming legacy—he even claimed that he spent ten hours a day on ranch projects versus two hours writing to pay the bills. His hand-shaped terraces fertilized by manure from his purebred livestock are modeled after ones observed in Asia; they still attract attention today on an inholding planted in grapes belonging to London’s heirs, as do the offspring of the 80,000 eucalyptus seedlings he began planting in 1910—a failed experiment intended to produce a hardwood crop. Standing with them are the twin concrete block silos erected by his workers in 1913 and 1915, the “Pig Palace,” a circular stone piggery he designed himself, and the curving stone dam that turned his lake into an irrigation reservoir.

To discover London’s inspirational wellsprings, park visitors do well to search out the lesser-known natural features of the park. Anyone with a little time and the energy to hike a few miles can encounter the natural places London wrote about while revealing his own transformation in the “cleansing bath” of nature. In my years of backcountry patrols as a ranger, I often enjoyed trying to locate the more obscure sources.

Conveniently, one of the most poignant spots hides in plain sight near Jack London’s grave, a third of a mile out on the Wolf House Trail from the visitor center parking lot. Look for the one tall evergreen tree enclosed by a picket fence, growing near two pioneer children’s graves (the moldering hand-hewn markers are inscribed “Little Lily” and “Little David”). This nonnative memorial tree is the only mature Arizona cypress on the mountain. It was here that the hero of the novel Burning Daylight (1910), along with his creator Jack London, first explored Sonoma Mountain and, attracted to the tiny graves by the green cypress’s distinctive shade, fell in love with all that they beheld. London asked his wife to lay his ashes to rest on the same knoll, when the time came.

Earlier on in the same book, London writes about his larger-than-life hero, nicknamed Burning Daylight, discovering a “California lily:”

It was a wonderful flower, growing there in the cathedral nave of lofty trees. At least eight feet in height, its stem rose straight and slender, green and bare, for two-thirds of its length, and then burst into a shower of snow-white waxen bells. There were hundreds of these blossoms, all from the one stem, delicately poised and ethereally frail. Daylight … took off his hat, with almost a vague religious feeling. This was different. No room for contempt and evil here. This was clean and fresh and beautiful—something he could respect. It was like a church.

- This cottage, built by a previous owner of the ranch in the1860s, was where London and his wife Charmian lived from 1911 until hisdeath in 1916. Currently closed to the public, it will eventuallyreopen as a new Jack London museum. Photo by Steven dosRemedios.

This rarely seen wildflower, Lilium rubescens, is also known as redwood lily. To find your own specimen, hike one mile to the lake (starting from the Beauty Ranch/Cottage parking lot) and continue uphill to the first switchback beyond the lake—another tenth of a mile. Between that switchback and the next, look off the trail 15 feet uphill (south) for a small wire-fenced enclosure that protects the redwood lilies from wild pigs and deer. In my experience, several years pass between actual bloomings. If the lilies are present, you’ll know them by their extreme height—up to six feet these days (versus London’s eight)—and their fragrance, which perfumes the air around them. The flowers may not appear until June or July; they consist of multiple petals that start out white with magenta speckles and darken with age to a pinkish-purple wine color.

Discovering sites such as these that show up virtually unaltered in books written a hundred years ago has the uncanny effect of transporting me through time and imagination into the author’s mind. I can almost see city-weary London standing there in contemplation, formulating his narrative:

Daylight’s delight was unbounded. It seemed to him that he had never been so happy. . . . He was keenly interested in everything—in the moss on the trees and branches; in the bunches of mistletoe hanging in the oaks; in the nest of a wood-rat; in the water-cress growing in the sheltered eddies of the little stream.

Although Daylight seems the instant convert, London sends him back to the city one more time before allowing him to return to the land, concluding about him that he was still “unaware in his self-consciousness of the potent charm of nature that was percolating through his city-rotted body and brain.”

London was likely speaking as much about himself as about his character. Raised on East Bay waterfronts in a suffocating urban environment, he began his career writing fiction—such as White Fang and “To Build a Fire”—about the pitiless wilderness he had encountered in the rugged Klondike. He finished his career in his cottage, where he died, writing about the redemptive aspects of nature and riding the trails of his Beauty Ranch. After regaining his own private Eden in the Sonoma Valley, he promoted the idea that through an atavistic “return to the soil”—careful stewardship, conservation, and nurturing—modern men and women stood to gain everything: “If we redeem the land, it will redeem us.”

We end our literary natural history tour of the park where we began, under Pacific madrones and manzanitas, with The Valley of the Moon, his most notable work on the theme of agrarian redemption. The novel opens with Saxon Brown ironing in a sweatshop and her husband-to-be Billy Roberts brawling in an Oakland teamster dispute, and ends idyllically in a forest glade on Sonoma Mountain with a doe and spotted fawn gazing between trees at the newly settled heroes. In between they search through much of Central and Northern California and Oregon for the one ideal spot to sink down their roots. As they are about to abandon their quest as hopeless, thinking that their valley must exist only on the moon, they find it in the Sonoma Valley, entering a canyon situated just below what came to be Jack London State Historic Park:

They dropped down into the canyon, the road following a stream that sang under maples and alders. The sunset fires, refracted from the cloud-driftage of the autumn sky, bathed the canyon with crimson, in which ruddy-limbed madroños and wine-wooded manzanitas burned and smoldered . . . .

“I’ve got a hunch,” said Billy.

“Let me say it first,” Saxon begged. “We’ve found our valley.”

Getting There:

From the south, take Highway 101 or Interstate 80 to Highway 37, toward Sonoma; go north on Highway 12/121 to Sonoma. From there, take Highway 12 north eight miles to Madrone Road; turn left. After a mile, turn right on Arnold Drive; after two miles, turn left on London Ranch Road, which ends at the park. From the north, from Highway 101 in Santa Rosa, go east 15 miles on Highway 12 to the Glen Ellen turnoff onto Arnold Drive. After one mile on Arnold Drive turn right onto London Ranch Road. $6 parking fee.

- Map by Ben Pease

Jack London: Additional Resources

Online Archives

London Papers

The Huntington Library’s archive of Jack London’s papers, numbering about 60,000 items, is the largest London collection in the world. The collection’s online catalogue includes correspondence, drafts, and notes for nearly all of London’s writings as well as numerous other items illuminating the details of London’s life and his extensive interests and endeavors.

www.huntington.org/LibraryDiv/jlpapers.html

The Jack London Online Collection

Sonoma State University’s extensive Jack London Online Collection provides links to numerous resources including documents, images, and writings describing London’s life, travels, and work.

The site also includes over a hundred images of the London family, friends, and acquaintances, and the places, voyages, and events formative in their lives. Of particular interest are images of Beauty Ranch, including the innovative Pig Palace, which London laid out in a circle around a central feeding house in order to save labor.

london.sonoma.edu/Images/London/

The World of Jack London

This web site’s title says it all. A user-friendly site devoted to anything and everything Jack London.

Hike and Trail Information

Jack London State Historic Park

The California State Park’s web site for the historic park located in Sonoma’s beautiful Valley of the Moon.

www.parks.ca.gov/default.asp?page_id=478

California State Parks offers a free and very informative park brochure providing biographical information on Jack London as well as descriptions of the various buildings found at this historic state park. The brochure also includes detailed maps to guide hikers and mountain bikers who want to explore the numerous trails that traverse the surrounding state parkland.

Download the brochure (840K PDF):

www.parks.ca.gov/pages/478/files/JL.pdf

Sonoma Ridge Trail Hike

Jack London State Park’s many trails offer hikers of varying abilities the chance to explore trails that meander through dense oak and maple canopy that open to breathtaking views of the Valley of the Moon. The newest of these hikes is the Sonoma Ridge Trail, which begins 2.2 miles from the upper parking lot at Jack London State Historic Park.

www.bahiker.com/northbayhikes/jacklondon.html

www.jacklondonpark.com/ridge_trail.htm

Docent-led Tours and Hikes

Jack London State Historic Park offers docent-led tours for the public that focus on Jack London, his life and activities on the Beauty Ranch, and the natural environment of the park. Reservation are required. To reserve a spot and read detailed descriptions of the various hikes available, visit www.jacklondonpark.com.

—Compiled by Jessica Taekman

.jpg)