Wildlife in the San Francisco Bay can be rather elusive. If it’s not flapping quickly by, it’s diving for a meal, cruising the ocean floor, or intermittently surfacing to breathe. In other words, it can be hard to take a closer look. That is, until you wade into an eelgrass meadow and literally feel the wildlife brush against your legs.

Beginning this summer, there will be more of those meadows to visit. In June, Kathy Boyer, an associate professor of biology at San Francisco State University’s Romberg Tiburon Center, began a nine-year effort to restore 70 acres of Zostera marina, the native eelgrass in the San Francisco Bay. The work is funded by settlement money from the Cosco Busan oil spill that emptied 58,000 gallons into the San Francisco Bay in 2007.

Using two methods, transplanting and seed dispersal, Boyer and her team of researchers, students, and volunteers will restore the equivalent of four football fields per year in designated sites throughout the Bay. The planted areas should naturally expand, helping the researchers achieve their restoration goals.

It’s the first major eelgrass restoration project the Bay has seen in years, primarily because of the cost and logistical planning necessary for planting underwater meadows. It takes long hours and very physically fit people, said Boyer, not to mention trained scuba divers, research vessels, and gear.

Currently, the team is focusing on two sites within the San Rafael and Corte Madera bays, where at sunrise during low tide they can be found securing transplants with bamboo stakes into the sediment or deploying brightly colored buoys with seed bags attached. The seed buoys passively sow seeds that have been harvested from various meadows throughout the Bay, mimicking the natural seed dispersal that occurs from detached, floating plants.

“SF State has a lot of history in developing [eelgrass restoration] techniques within the Bay, and we knew that they had a proven method to do it,” said Natalie Cosentino-Manning, the restoration program manager for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Restoration Center.

Also partnered on the project is Keith Merkel of Merkel and Associates, a San Diego-based consultant who has a history of mapping suitable habitat for eelgrass restoration in the San Francisco Bay.

“This is the biggest effort like this that’s ever been done in the SF Bay,” said Boyer. “We’re trying to do it in a really experimental way so we can learn a lot hopefully about where we should be collecting the plants, what sites will work for us, and what planting methodologies will work best.”

Herring benefit too

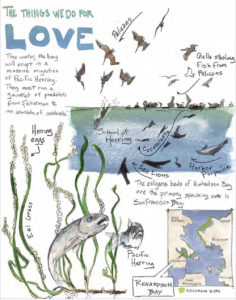

The project will restore not only eelgrass beds but also herring spawning grounds, both of which were targeted in a list of 12 restoration projects outlined by the Cosco Busan Damage Assessment and Restoration Plan. Sampling and photographs after the spill showed high accumulations of oil in areas where Pacific herring lay eggs, in particular in the eelgrass meadows of Tiburon’s Keil Cove.

Herring come into the Bay from roughly December to February to spawn; they do so not continuously, but in pulses. If this summer’s transplanted eelgrass shoots survive and spread, herring will have multiple acres of new habitat to lay eggs. The seedlings, if successful in taking root, won’t be available as habitat until next spring.

Restoration doesn’t come easy

San Francisco Bay property lines don’t always end at the waterfront. Much of the submerged land of San Francisco Bay is owned by private landowners. The researchers first had to hunt down these landowners to request access to selected restoration sites.

Fortunately for the project, the landowner that Boyer and her team approached — the Marin Rod and Gun Club (MRGC) — shares similar interests and goals in habitat restoration. The restoration will benefit people who care about fish from a conservation standpoint, and also those who just want to fish.

“Club members have come to take great pride in our coordination with the scientific community in both our eelgrass and native oyster projects,”said MRGC’s executive advisor Todd Meyer.“What Kathy’s doing with eelgrass is just massive. I think it has the greatest potential of changing for the better the ecosystem of San Francisco Bay.”

Moving forward

For the duration of the summer, seed buoys will drift within their designated plots, sowing what researchers hope will be an eventual rebound of eelgrass populations in the San Francisco Bay. In September, the seed buoys will be removed and continual monitoring will begin throughout the restoration sites.

The longevity of the $2.5 million program lends itself to adaptive management.

“Each year we want to learn something that helps us to decide what to do the next year,” said Boyer. “Are we going in the right direction or do we need a course correction?”