When there is no wind, it is eerily quiet on the ridge atop the Tiburon Peninsula. A very faint hum fills the air, a gentle soughing generated by the endless rush of cars on Highway 101 in the distance. Only occasionally can one hear the droning of an aircraft overhead, the shriek of a redtailed hawk circling in the thermals, or the chatter of a flock of dark-eyed juncos under the bushes. That there is hardly any sound at all seems surreal, given that the unobstructed 360-degree view from the top of Ring Mountain encompasses much of the bustling metropolis of the Bay Area, along with many of its natural landmarks.

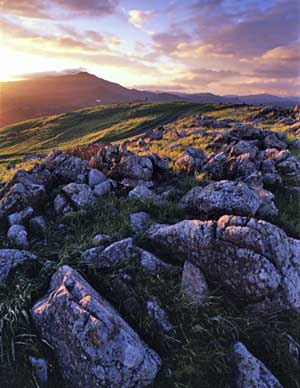

- On a clear day at Ring Mountain on the Tiburon Peninsula, you can get a 360-degree view that encompasses San Francisco, Mount Tamalpais, San Pablo Bay, and Mount Diablo. Photo by Gary Brand.

Dark and mighty, Mount Tamalpais dominates the skyline to the west, while Mount Diablo looms high over the East Bay. To the south, the silhouette of downtown San Francisco with its signature skyscrapers rises from the thin layer of fog. Without a doubt, the calm and the breathtaking vistas make this windswept ridge one of the most valuable pieces of real estate on the planet. But there is no acreage for sale on Ring Mountain, nestled between the Marin County towns of Tiburon and Corte Madera. Instead the area is a preserve, giving the public access to its sweeping views, unique natural beauty, and sense of calm worthy of a temple for meditation.

However, the mountain itself has a history that is anything but quiet. The rocks underneath the hiker’s feet have been squeezed and folded, smashed and pushed, chemically altered and physically tortured. Indeed, the geologic story of Ring Mountain is probably among the most violent of the entire Bay Area. Scientists believe that most of the rocks underlying this modest 602-foot-high “mountain” once lay at the bottom of an ocean, and beginning about 165 million years ago, they were driven many dozens of miles into the earth’s mantle in a process called subduction—only later to be pushed back up to the surface, displaying the scars of their voyage into the fiery cauldron deep inside our planet.

As you stroll up the hillside from one of the trailheads at Paradise Drive or Via Los Altos off of Tiburon Boulevard, the scene does not seem strikingly different from that along many other trails in eastern Marin. Open grasslands, which explode with colorful wildflowers in the spring, alternate with oak, bay, and manzanita thickets; poison oak grows almost everywhere. But you will soon notice the big rocks and boulders, which range in volume from a few cubic feet to the size of a small house. They seem to protrude from the grasses and shrubs in random fashion almost wherever one looks. Some are darkish green; others have a reddish-orange hue. Almost all are covered with colorful patches of lichen, which glow in various shades of green, gray, and yellow.

- The federally threatened Tiburon mariposa lily – discoveredin 1971 – grows here and nowhere else. About 40,000 of the plants remainin the Ring Mountain Open Space Preserve. Photo by David M. Davies.

Were Ring Mountain located somewhere in the Mediterranean, ancient texts might speak of a jealous cyclops who had cast the boulders about in an angry fit. But geology tells another story, perhaps more plausible but by no means less tumultuous. Almost without exception the rocks on Ring Mountain belong to a class scientists call metamorphic. Metamorphism is a process by which rocks—which may be sedimentary, igneous, or other metamorphic rocks—change in composition and appearance, losing their original identity. In simple terms metamorphism is very much like baking bread. One starts with separate ingredients, such as flour, eggs, and yeast. But the moment these are mixed together and thoroughly kneaded, they’re transformed into a dough. During baking the dough changes once more and out comes a loaf of bread whose ingredients have been converted into a completely new state.

The same happens with sedimentary rocks like sandstone or chalk (limestone) when they are forced into the bowels of the earth. The deeper they wander, the hotter they become and the more they are compressed by the weight of the rock above. In most cases, the pressure finally grows so great that the molecular structure of the rock’s constituent minerals is altered and it emerges as a new kind of rock. Depending on the temperature, pressure, and length of time spent in this subterranean oven, the same set of initial rocks can be transformed into various different metamorphics.

In the same way an experienced baker or a sophisticated gourmet can speculate about the original ingredients of a loaf of bread by looking at it and tasting it, geologists can infer the origins and the history of metamorphic rocks by analyzing the crystals they contain. Most of the rocks on the slopes of Ring Mountain and some along the crest show exemplary pieces of minerals called amphibolite and eclogite, the latter sometimes “contaminated” with tiny garnets. These crystals form only when the pressure is 20 to 30 thousand times the normal air pressure at sea level and the temperature is several hundred degrees. This in turn means that these rocks must have been squeezed and kneaded several dozen miles down within the earth. In short, they must have undergone intensive metamorphism; hence they are called high-grade metamorphics.

Geologists believe that the high-grade metamorphic rocks on Ring Mountain were originally basalts that came up from the earth’s mantle through vents deep under the Pacific Ocean. These ocean-floor basalts were then transported east and north by the movement of tectonic plates before being swallowed deep into the interior of the earth along the western margin of North America about 165 million years ago. This process of subduction is still occurring today in the Pacific Northwest and under the west coast of South America. There, most of that oceanic crust gets recycled to the earth’s surface during volcanic eruptions in the Andes and the Cascades. In contrast, the high-grade metamorphic rocks of Ring Mountain stayed in the bowels of the earth for millions of years. In a still unknown process, they were regurgitated to the surface, perhaps squeezed through fissures like toothpaste being pushed out of a tube. The surfaces of some rocks near the summit of Ring Mountain still contain noticeable grooves, believed to be scratch marks from their voyage up from below.

- Native wildflowers like Tiburon paintbrush and Marin dwarfflax have adapted to nutrient-poor and toxic serpentine soils, such asthose found on the top of Ring Mountain. Photos by Doreen Smith

Low-grade metamorphic rocks are very common all over the world. Much of the Coast Range of California is made of such material. There are far fewer places where the results of high-pressure metamorphism are exposed on the earth’s surface, and Ring Mountain is the prime location for such rocks in Northern California. These rocks and boulders poke up along the slopes through a soft and slide-prone landscape of what geologists call mélange—a jumble of rocks crushed in the ancient plate collision or broken down by recent erosion. To the uninitiated hiker, however, the signs of twisting torture these rocks underwent are not always obvious. Some have shiny surfaces glittering with mica; others might expose large crystals were they not covered by lichen. One of the most obvious signs of the rocks’ dramatic past can be seen on the south face of Turtle Rock, a massive boulder that sits between the mountain’s two crests. There the rock’s layers are bent and folded, as if they had been kneaded by a giant baker.

While there are many bushes and thickets on the slopes of Ring Mountain, the expansive ridgetop is almost barren. This makes the hundreds of rocks that “litter” the preserve’s two crests and the saddle in between more obvious. Most of them, however, do not belong in the same class of rock found along the slopes. The rocks on top are mostly made of serpentinite, California’s official state rock. This rock is also metamorphic, but it was never subjected to the high temperatures and strong pressure that formed the boulders along the slopes. Although serpentinite can be found throughout the Coast Ranges, the outcrops on Ring Mountain are certainly some of the more impressive ones locally. Most serpentinite has a blue-greenish shine to it, but it can also display an orangish hue, which on Ring Mountain is amplified toward evening, when the rocks shine in the alpenglow of sunset.

Like every other rock, serpentinite crumbles and erodes when exposed to wind and water, creating the mineral basis of the soil around it. But in contrast to most other rocks, the soil generated by California’s state rock is highly infertile and even toxic to many plants. Biologists sometimes refer to the ecosystems in serpentinite-rich areas as “serpentine barrens,” indicating that only a few plant species can survive on such soil. Serpentinite lacks many primary plant nutrients such as nitrogen, potassium, and calcium. Instead, it contains large amounts of magnesium, nickel, cobalt, and chromium, which are anathema to most plants. In addition, serpentine soils usually drain very rapidly and don’t hold much moisture—making survival impossible for many plants, particularly in the California’s dry summers.

But evolution being what it is, some plants have taken advantage of the relative lack of competition and adapted to live well on the normally toxic mineral diet offered by the soils on Ring Mountain. Several of these species, like the Tiburon mariposa lily (Calochortus tiburonensis), are endemic to this area and can be found nowhere else on earth. This plant, with light yellow-green blossoms that have reddish or purplish-brown markings, was discovered only in 1971. It blossoms from March to June, and the population of 40,000 or so plants on Ring Mountain was classified as “threatened” by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in 1998. Other rare plants on Ring Mountain include the Tiburon Indian paintbrush (Castilleja affinis spp. neglecta) and the Oakland star tulip (Calochortus umbellatus). These are by far the most remarkable plants on the mountain, but the preserve boasts impressive displays of more common native wildflowers, such as goldfields, blue dicks, and several kinds of lupine.

Though scientists have been discovering plant species here well within living memory, people have come to this mountain for thousands of years. About 30 of the mountain’s boulders are decorated with unusual curvilinear markings, ovals, and circles. These are definitely not a product of metamorphic alteration. Instead, they are Indian petroglyphs, the only known in Marin County. Despite intensive research, archaeologists still are not in agreement as to when they were carved and what they signify. What is clear, however, is that the site was used by Coast Miwok Indians. Mortar holes and other artifacts found here have been dated at nearly 2,400 years old.

- Map by Ben Pease

Recent preservation efforts, by the Nature Conservancy and others, are not the only reason the landscape on Ring Mountain today looks very similar to its appearance before the Spanish settlers arrived. The mountain was part of the first Mexican land grant north of the Golden Gate. In 1834 John Reed, a Dubliner who had lived in Mexico for a while, was awarded the Rancho Corte Madera del Presidio, which included the entire Tiburon Peninsula and the current towns of Corte Madera, Larkspur, and Mill Valley. As the towns around the mountain grew, the Reed family kept Ring Mountain and used it for cattle grazing. Reed Ranch Road, which approaches the preserve from Richardson Bay, is a reminder of old ranching days.

Now, however, there are no cattle on the ridge. Long ago, the ranchers sold the land to housing developers, who hoped to capitalize on this prime piece of real estate. As more and more homes were built on the ridge to the east and west, and on the lower slopes to the south, a grassroots effort arose to protect the upper reaches from further development. After a lengthy battle with developers, the Nature Conservancy established a preserve here in 1983. Twelve years later the property of about 400 acres was transferred to the Marin County Open Space District, which now manages the preserve.

Today, the Ring Mountain Preserve is indeed a peaceful refuge, high above the busy roads and towns of east Marin. With its unique geology, it is also a window into the deep interior of our planet and its violent past.

Getting there:

By car: The main trailhead is on Paradise Drive east of Corte Madera. Take the Paradise Drive exit from Hwy. 101. Just past Westwood Drive is a small sign on the right for Ring Mountain. Park along the road. There are no facilities. Or continue along Paradise Drive for another half mile and turn right on Taylor Road. There is limited parking at the end of Taylor Road.

By bus: Golden Gate Transit Bus #9, weekdays only, can get you from the Tiburon Ferry Terminal to Reed Ranch Road. From there it is a steep uphill hike to the trailhead.

.jpg)