This essay was produced in partnership with the Laboratory for Environmental Narrative Strategies (LENS) at UCLA.

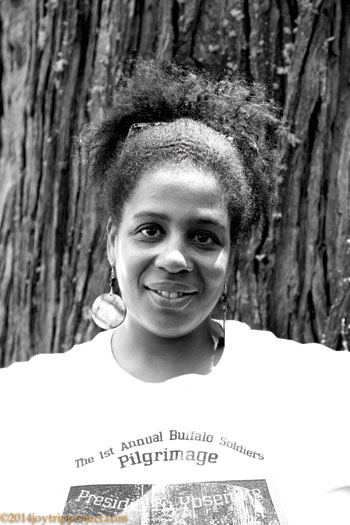

There were copters overheard all day. I was at work in Outdoor Afro’s office in downtown Oakland in the days after the fatal shooting of a black man by a white police officer in Ferguson, Missouri. It was a really tense time in Oakland, as it was in many cities around the country. The city was bracing for violence.

I’ll never forget that moment. Personally, I felt that I didn’t want to go out and be in the streets and be a part of that kind of response. But I knew that my work had to do something. I was walking to my car, feeling like I needed to get away from downtown. And then the answer came. And the answer was nature.

The voice in my head said, “You do nature, Rue. That’s your lane.”

So the next day I got on the phone with Outdoor Afro leaders around the country and some of our partners. We decided to do what we called “healing hikes” in the days to come. That first time, the leaders in the Bay Area gathered in a clearing in the Oakland Hills and took some time to ground ourselves. We did some yoga poses and really set our intentions for what we wanted to create and be a part of that day around healing. Then we started hiking.

We worked our way down into a beautiful redwood bowl and wound up walking along a stream. We were sharing and listening to each other. And I realized, we were doing something that African Americans had always known that we could do. And that was to lay our burdens down by the riverside.

Coming out of that experience, we shared with one another our resolve for how we would do something different in our neighborhoods, in our homes, in our workplaces, to effect change. We’ve continued to do healing hikes, while remaining sad that the reasons for doing them persist. We did a series of healing hikes after Orlando to bring our communities together, people who want to get together and just try to make sense of the world as it is today. And nature provides that platform for it to happen.

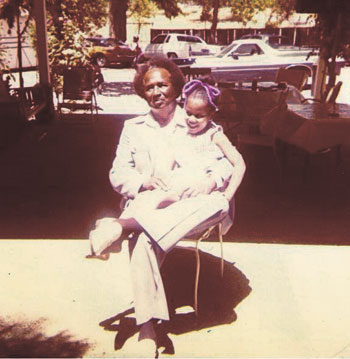

I’ve been asked a lot about Outdoor Afro’s role in the movement for black lives. Our response has been to double down on black joy in nature. This is the new narrative that we want to continue to shout from the rooftops. It’s about finding our story in nature. We find compelling stories that help people feel a deeper connection to our outdoor spaces. We’re also reactivating some of the things people might have done when they were children, with a grandparent or a caregiver, connections and community they may have lost, but can regain today. I am also always impressed by the amount of our history that’s contained in some of the places that we visit.

The story of Outdoor Afro really begins, for me, in my own family. When my father migrated from East Texas to California after World War II, he brought with him a passion for the outdoors. We lived in Oakland, but he invested in a small piece of land in Lake County.

We had cows and pigs. I learned to hunt and fish. It became a place where we connected with nature. But it was also a place of deep connectivity between our family members. We had all kinds of celebrations and cookouts. And for me, as a child, the land was a laboratory. I was able to see stars that I couldn’t see at home in Oakland. I was able to monitor the life cycle of the tadpole that became a frog in the creek nearby. I could ride my bike along country roads, hearing only the sound of my own tires on the pavement.

We had a bountiful garden, and there was a synergy between our home in Oakland and the ranch. We did harvesting, canning, preserving, and smoking. We had meat, fruit, and vegetables that we laid up for winter and we enjoyed very much. But it wasn’t just hands on the land and a superior environmental education, it was a lifestyle. My dad was the architect of the space, and my mom was the hospitality of it. There was a standing invitation to come rap on the door. You were not only welcome, but there was plate of food for you. It was a really happy way to grow up. And it planted the seeds of both hospitality and nature that are at the core of Outdoor Afro now.

When I was 20, I decided to build on my outdoor connection by joining an Outward Bound course in the Sierra. I had lots of experience in the outdoors, but I had never climbed a mountain. As I was packing and trying to save money, I decided not to bring some things, like a headlamp. I thought, “I have a flashlight, why do I need a headlamp too?” It seemed a little redundant at the time. Little did I know we’d be doing a night climb. And when the sun set, I found myself starfished on the side of a mountain slope that I could not see anymore. I could feel it. But I couldn’t see anything above me or below. And I completely broke down. I didn’t think that I could go on. But the instructor called down to me and he said, “Rue, trust your feet.”

Those words helped me get steady and solid and remember that I had something deep inside of me. And I dug in and got to the top. That was a big moment of revelation, for me, when I understood nature as a powerful teacher. And at the precipice of adulthood, living on my own for the first time, it was exactly the lesson I needed to learn.

I’m still trusting my feet. Sometimes I don’t know what just happened. Sometimes I don’t know what’s ahead. But I can dig in and move forward. It all came together for me in 2009. I was divorced, with three children and an unfinished undergraduate degree, when I decided to go back to school. I was blessed to have really good mentors who asked great questions of me at UC Berkeley. I was pondering graduate school, when one asked me the question that I think everyone should be asked, and that is, “If time and money were not an issue, what would you be doing?”

I opened my mouth and my life fell out.

I said, “Oh, I’d probably start a website to reconnect African Americans to the outdoors.”

Two weeks later, Outdoor Afro was born.

Outdoor Afro began as a blog. We grew up on Facebook and Twitter. I put out a call and many voices responded. As I wrote and posted photographs about all of the things I loved about the outdoors, all of the experiences that I had growing up in my family, and sharing the experiences I was continuing to have with my children, people said, “You know what? I actually love nature too.” People who looked like me, people who were in my age group said, “I love nature.” I realized then that what we had was a problem of visual representation, because we weren’t seeing our images reflected back to us in the mainstream outdoor-oriented magazines of the day.

The audience that emerged—African American women between the ages of 35 and 44—had been ignored. And they’re an amplifying audience because they don’t show up alone. And they make decisions for generations in a household. I found that when you get a black woman outdoors for a group event, she’s going to come with a child, she’s going to come with a partner, she’s an aunt, she’s a caregiver, she’s active in her church or sorority. These women make up about 70 percent of Outdoor Afro now.

I thought I was looking for the wildlife biologist, the NOLS-certified instructor, or people who had long, professional experience in the environmental education field. But I found that our best leaders were the butcher, the baker, the candlestick maker, people who came from all kinds of professional backgrounds. They are human rights attorneys, real estate professionals, college lecturers, preschool teachers—you name it.

I had no idea what an Outdoor Afro leader was going to look like when I first put out a call on social media asking, “Who wants to be an Outdoor Afro leader?” I thought I was looking for the wildlife biologist, the NOLS-certified instructor, or people who had long, professional experience in the environmental education field. But I found that our best leaders were the butcher, the baker, the candlestick maker, people who came from all kinds of professional backgrounds. They are human rights attorneys, real estate professionals, college lecturers, preschool teachers—you name it. We now have more than 60 leaders in 28 states around the United States, who are connecting 17,000 people a year to outdoor experiences right in their own backyards. The thing that they all share is a fire in their bellies to connect people to nature.

We also began looking at the obstacles African Americans face in getting outdoors. We conducted some surveys and discovered some revealing results. Gear is huge. Not understanding the things that they need—why they need them, or what they might already have in their closets so they don’t need to go out and purchase—is a daunting barrier. Fears and perceptions about safety are very, very important. It’s crucial that people feel safe in the outdoors. And lack of transportation is a significant problem. Sometimes nature experiences are so close but so far away, especially if you don’t have access to transportation or you’re relying on public transportation on weekends, when access is limited.

It’s also true that the outdoors, especially remote wilderness areas, have not always represented safety. We have a legacy in this country of terror that has occurred in the woods, under the cover of night. So it’s no wonder that we’ve found, in our experience with Outdoor Afro, that people feel more comfortable connecting with nature in groups rather than alone. And then there is the stress that many of us feel in our lives, no matter who you are or where you live. We’re over-scheduled. We don’t know how to fit nature experiences into our lives. The number one reason African Americans are not getting outdoors is time—or rather the perception that there is not enough time to get outdoors. So at Outdoor Afro, we are working to respond to each of those issues and provide solutions for these challenges that people either perceive or that are, indeed, very real. We often do things that are not so physically active—the things that human beings have been doing from the beginning—like sitting around a fire and sharing our stories.

A couple of years ago, I decided I wanted to try to reconnect with really wild nature myself. I get outdoors a lot, but I had not spent much time in capital-W “Wilderness” since I climbed that mountain in the dark. And the Sierra Club invited me along on a trip to the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. It was a magnificent experience that gave me a new level of appreciation for the wild.

Soon after we landed and unpacked, a grizzly bear reared up from the brush surrounding our remote campsite. And we did the things that humans do when we’re confronted with wildlife like that. We tried to reason with the bear. “Go away, bear. You don’t want to be here, bear.” But we were terrified. I know I was terrified.

This was definitely no Yosemite bear. This bear might not have ever seen human beings before. He may have been just as curious about us as we were afraid of him. And then, with a whiff of the northern air, he disappeared. It was at that moment I realized that we were in that bear’s wild. We were not significant. If the bear had decided to enjoy us for lunch that day, the wild would roll on in its strength, its resiliency. That moment pushed the reset button on my humanity. And I know I am better because of that encounter with the wild.

When I got home I thought a lot about that wild. I wondered how does the experience that I had in the bear’s wild relate to what’s happening in places like East Oakland, where people connect with the outdoors in lowercase “wild” ways, if they can at all. They’re not investing thousands of dollars to go to remote areas like the Arctic. And they may never be able to do that. Both the uppercase Wilderness and the lowercase wild are vital.

I realized then that we missed an opportunity about 50 years ago, when the Wilderness Act and the Civil Rights Act were passed in the same year, 1964. I began asking people who were around at that time, “Were there conversations happening between these two caucuses?” And the answer I heard has always been, “No.” I’ve come to believe that had we, at that moment, come together and realized that the crucial conversation is about protecting vulnerable places and vulnerable people, then we might have a very different environmental and conservation movement today.

We’ve learned many, many things over the years. Three things stand out for me. First is relevancy. We have to foster ways that outdoor experiences can meet people where they are and reflect and tell their stories. Second is leadership. In the beginning, I was really focused on participation. But it’s leadership that matters. It’s leadership that engages adults who, like I was in my mid-30s, are interested and willing to invest their time in becoming leaders in the outdoors and bringing along their community.

And then, finally, it’s about the long view. There is now a growing clamor for diverse participation in the outdoors. As a result, we often want to rush people and organizations ahead. But this is really about a generational shift that is under way. It’s one I look forward to. So when our work is done there’s not going to be a big parade down Main Street. There will not be balloons falling from the sky. No. It’s going to be a quiet moment. We will look up and we’ll see all people participating in the outdoors. And it will be no big deal. Just us. In the outdoors.

UCLA’s Laboratory for Environmental Narrative Strategies is an incubator for new research and collaboration on storytelling, communications, and media in the service of environmental conservation and equity. Learn more at https://www.ioes.ucla.edu/lens/