From a homemade shelter in the heart of Mendocino County’s oak woodlands, nature writer Kate Marianchild watches and waits, jotting down notes on the often surprising behaviors of the wild animals, plants, and insects that call the woodlands home. A decade of close observation has yielded Kate’s first book on her beloved ecosystem, Secrets of the Oak Woodlands, recently published by Heyday.

What inspired you to write Secrets?

When I moved to inland Mendocino County in 2001 I fell in love with this place, with its rolling hills covered with oaks, madrones, buckeyes, bays, and manzanitas. First I focused on learning the local birds, but soon I wanted to know more than their names — I got interested in what they ate, what they needed for nest material, where they slept at night. And that led me to research the plants they depended on, the pollinators of those plants, the mammals and reptiles that ate or took shelter in those plants, and so on. Pretty soon I was like a garden spider, alive to everything happening in the web around me.

Each chapter in the book contains interesting info about different species that inhabit the oak woodlands and their interactions. How did you come up with this format?

I can easily become enamored of an individual species, such as the California newt, or a group of organisms, such as gall-forming wasps. Once hooked, I devour all the information I can find about a species until I have a fairly complete portrait, so I made it my job to tunnel through dense science articles to find little known nuggets of information and to document interspecies relationships.

Tell us about one of the species highlighted in the book, and why you find it fascinating.

Woodrats are docile soft-furred animals, with big ears and big eyes, that build what appear to be the most complex aboveground houses of any mammal in the world. Inside of what appears to be a messy jumble of sticks, there are sleeping chambers and birthing nests lined with soft materials; pantries––sometimes with manzanita berries in one, mushrooms and truffles in another, and acorns in a third; leaching rooms where toxic toyon, coffeeberry, or sage leaves outgas before being eaten; and designated latrine areas. The rooms are connected by a network of hallways, and light and air enter the structure though openings on every level.

The woodrats’ skill as builders and as masters of climate control benefits many other species who take up residence in their homes as uninvited guests. In fact, woodrats provide critical shelter to so many other species, like frogs, salamanders, deer mice, brush mice, and centipedes, that they are considered a keystone species, one that has a huge impact on biodiversity.

We really enjoyed your Bay Nature “Signs of the Season” piece on acorn woodpeckers a few years back. Why do you find them so remarkable?

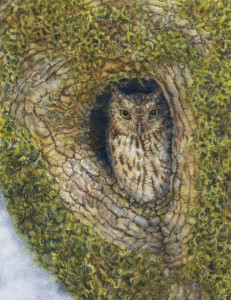

Acorn woodpeckers are animated and talkative animals who kept me company when I was ill with Lyme disease. They live in clans and do everything communally—sex, nesting, child-rearing, food storage, food consumption. They even perform pseudo-copulations in group gatherings before heading into their communal roost cavities for the night. They appear to have the most complex social structure of any vertebrate species in the world, including humans.

On top of that, acorn woodpeckers are the only species in the world known to drill individual holes in wood to cache individual food items — in this case acorns.. For the record, there is a 100-year-old myth that acorn woodpeckers store acorns so they can later eat the larvae inside them. Not so! They’re after the acorns themselves.

Your book also covers the unlikely partnership between badgers and coyotes. Can you tell us a little about that?

We rarely see badgers, but they live here, generally hidden in their underground burrows during the day, but sometimes visible in the daytime, hunting ground squirrels alone or with coyotes. As far as I can tell, it’s strictly a business relationship, an experience that has proven to be beneficial to both parties. You can see online images of coyotes and badgers traveling together to their hunting destination, a ground squirrel colony. The coyote waits in a strategic place while the badger digs. When a beleaguered ground squirrel pops through a thin layer of soil at the end of an escape tunnel, the waiting coyote leaps on it. On the other hand, if a coyote flushes a ground squirrel in a meadow and chases it toward its burrow, a strategically positioned badger will be able to dig furiously with its huge curved claws and nab it before it disappears.

Are you trained as a naturalist?

No. I’ve been teaching myself through observation and research for about the last ten years, and really shouldn’t be allowed to call myself a naturalist. The “real” naturalists have been doing it their whole lives. My academic background in science consists of one high school biology class and one high school physiology class; my study of Chinese hasn’t helped much! But a broad definition of the word naturalist should include people like me who are looking at, wondering about, and learning about the lives and interactions of the inhabitants of ecosystems. And in becoming a naturalist I have returned to my first love: As a child I roamed the hills of a then-rural Malibu and developed a keen eye for form, texture, color, movement, and sound in the natural world.

Your bio mentions that you actually live in an oak woodland, in a yurt. Tell us about living and working in this environment.

My yurt is part of a widely spread cluster of 14 structures surrounded by 160 acres of wild oak woodlands. We’re a community of sorts—we have a benevolent landlord who gives us a decent amount of control combined with responsibility. At monthly meetings, we hash out decisions about the land, road maintenance, the water system, and who can and can’t live here.

I love living in this oak woodland because something interesting is always going on, even if very subtly. I am especially happy working outdoors under the thatched-roof “palapa” I built. When I’m outside I feel connected to plants, animals, and even to distant people. These days I’m watching California bay trees to see if they are going to produce peppernuts this year (they seem delayed, perhaps due to drought), and I’m looking to see if quail coveys are smaller, another likely consequence of drought . Yesterday “Crooked Tail”, a lizard friend of mine, reappeared by his woodpile after an absence of almost a month. I’m guessing he had to recover from the huge energy demands of breeding season. I’m also noticing that no baby lizards are showing up around my yurt, but they are showing up near our lake, possibly another drought phenomenon, as lizard egg membranes need to continuously absorb water from the soil.

So the wildlife keeps you company?

Yes. While I’m working, I face my bird feeder, which is about 10 feet away and visited by a constant stream of acorn woodpeckers, house finches, white breasted nuthatches, and oak titmice. These birds are such good company that the feeling of isolation I normally have when I write indoors completely evaporates. A lusty male poison oak bush ten feet away (the new man in my life!) provides rich entertainment, especially in winter when golden-crowned sparrows decorate his bare branches, and in spring when beetles and other pollinators hover all around him.

Special discount for Bay Nature readers

Secrets of the Oak Woodlands: Plants and Animals Among California’s Oaks by Kate Marianchild is available with a 20% discount if ordered directly from Heyday Books.

Please use the following promotional code: BNOAKS

This special is good through September 14, 2014.