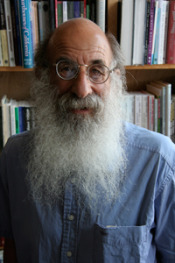

According to local legend, some four decades ago Malcolm Margolin was fired from his position as a seasonal naturalist with the East Bay Regional Park District for refusing to wear a uniform. But then, liberated from the constraints of a public agency job, the future Heyday Books founder took an unlikely sort of revenge: He wrote and published East Bay Out, a personal guidebook and homage to the East Bay parks. It became an instant classic for Bay Area nature lovers and the first title in his nascent local publishing empire.

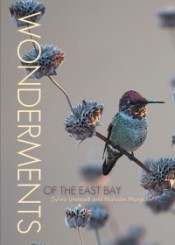

Forty years later, Margolin has returned to the parks in Wonderments of the East Bay, a new book marking the 80th anniversary of the Park District. He wrote the book with Marin-based nature writer Sylvia Linsteadt, a 2014 winner of the San Francisco Foundation’s James D. Phelan Award for emerging writers. We recently sat down with the co-authors at Heyday’s office in Berkeley to discuss the book and Margolin’s forty-year publishing career — and his concept of “wonderment.”

[Note: Margolin was the cofounder and first publisher of Bay Nature magazine.]

BN: Congratulations on celebrating the 40th anniversary of Heyday Books. How does it feel?

MM: Oh God, I don’t know – It feels like we’re the world’s oldest startup. When I come to the work, it still has a freshness to it; there’s a sense of novelty and interest, as if we haven’t the vaguest idea of how to do a book.

BN: How did you end up collaborating on Wonderments?

SL: I was working on a manuscript about animals in California in conjunction with the National Wildlife Federation, researching frogs. Then I worked at Heyday for a little while on some of their books, like an introduction to a literary guide to state parks.

MM: I love working with her and try to get her involved in anything I do!

BN: Malcolm, 40 years ago you published East Bay Out. How did this book come about, for those who aren’t familiar with the work?

MM: I’d written a book called Earth Manual and sold it to Houghton Mifflin for 10,000 bucks. Then I used that money to write and publish East Bay Out.

BN: Did you see Wonderments it as a sequel to East Bay Out?

MM: No, it’s a whole different form.

BN: How did it evolve?

MM: The East Bay Regional Park District is celebrating its 80th anniversary. They got hold of me and asked me to write something for their annual report. And since they fired me years ago, I owed them something; I figured I’d express my gratitude by writing it.

Then they wanted us to do a coffee table book for the anniversary. I knew exactly what that book would look like: It would have thick pages. It would have pictures of hills and oak trees. Maybe there would be a baby fox or a baby bobcat. And then you’d turn the page and there would be a quote from John Muir. But the era of picture books is over. They don’t have the same hold on the public imagination. I wanted something livelier, and something small.

At the same time I was working with Gordon Frankie at the Urban Bee Lab on his book California Bees and Blooms and I’d just found out about buzz pollination. It struck me as the most astounding thing I’d ever heard!

BN: Can you describe buzz pollination?

MM: Pollen is formed within the anther of a flower. Usually the anther splits open and the bee goes in and covers itself with pollen, then goes to the next flower and deposits the pollen. But some plants, like manzanitas and shooting stars, have flowers where the anther is rigid and doesn’t split easily so it’s hard to get the pollen out. So certain species of bumblebees have developed the most extraordinary trick: They cling to the rim of the petal, and vibrate their wing muscles, which sets up a sympathetic vibration in the thorax, which produces a middle “C” note. That middle C note causes the anther to tremble in sympathy, and the tufts of pollen come out. All this activity creates a negative electrical charge around the bee, so that when the pollen comes out, it’s attracted to that negative electrical charge and clings to the bee, which then goes off with the pollen.

BN: What’s the significance of wonder?

MM: I think I’m less interested in selling people on the wonderments of nature than selling them on the wonderments of language, of thought, of poetry. It’s like that wonderful line from Wallace Stegner: “No place, not even a wild place, is a place until it has had that human attention that at its highest reach is called poetry.” And it’s using the poetic imagination to set up a world parallel to the natural world. That is where I wanted to go with it.

SL: I think Wonderments tries to engage readers in the act of feeling wonder. It’s meant to evoke an emotional response.

MM: The reason I love your elderberry chapter, Sylvia, is not for the elderberries, but for the language you use to describe them. The concluding sentence, for example, about how the Miwok used elderberry for courting: “To select the right branch for flute-making and wooing, you had to find a branch with music in it. To do that, you waited for a windless day, and then you wandered until you found an elderberry with a leaf moving in the still air. Such a tree had music held inside.” I love that.

BN: Do children need to experience wonder?

MM: You need to instill a sense of magic and wonder. If you don’t have the rooting in magic, you’re lost as a human being. What you’ve got to teach children is the beauty, magic, and fairy tales.

BN: Do you have any plans to work together on future projects like Wonderments?

MM: Well, I don’t know whether we’re going to franchise this or not. There’s that marvelous Buddhist wisdom that repetition is the Buddhist definition of suffering. To do something again and again just because it worked is not my idea of a good time. I think it depends upon what brings out the best in us. The poetry of this – that spirit will be in whatever we work on together.

BN: What is your favorite wild place?

MM: The mind.

SL: The trail from Jewel Lake to Wildcat Canyon in Tilden Park is my favorite spot. I started going there when I began doing a lot of animal tracking. There’s a lot going on there because of Wildcat Creek, so it’s a crossroads for lots of animals. They have regular coyotes – I’ve noticed one that has a heel pad with a funny shape. And I see tracks of bobcats and deer and wood rats and salamanders.

BN: Do you find these tracks after a rain?

SL: Yes, or in the summer when it gets really dry, in August. The dust is so fine, you can see prints. There’s something really special to me about that little place; maybe it comes from creating a relationship with it.

MM: I’m not too good at hierarchies. There are places that I love at certain seasons of the year. I love Mount Diablo’s Mitchell Canyon at wildflower season. I tend to go there all the time. There’s a mortar hole on Albany Hill that speaks of people that once lived there.

And I have strong personal associations with places where things happened to me in these places, the people I was with. The experiences I’ve had are more important than the places.

There’s my wonderful friend Ernie Siva, a Serrano Indian who sings traditional songs that go on for four nights; he sings songs of the wanderings of divinities when the world was first made. One particular song he sang was very haunting. I asked what the song meant. Ernie said: “If you want me to translate the words, I can do that. But that’s not what gives the song meaning. What gives it meaning is who taught it to me, where I sing it in the cycle, who I’m going to teach it to, whether we’ve ever sung it at a funeral. And the fact that you’re asking me about it gives it meaning. This is what the meaning of the song is: the association I’ve had with these places.”

I had a another wonderful friend, Ernest Landauer, who wrote poems that I don’t even think he knew what they meant. I once saw him at the Monterey Market, and it was springtime. I was loading up the cart with apricots and peaches and plums and cherries and all these beautiful foods of spring, and I see Ernest coming by with his shopping cart, and it’s got three potatoes and four rutabagas, and a couple of turnips. And I said, “What’s wrong with you, Ernest? It’s springtime.” He said, “Sometimes you’ll find that the things you like best in this world aren’t the most interesting.”

So probably the trail I go on most often is the Claremont Canyon trail—the “Bataan death march”—that goes straight up that hill. I can’t say that it’s my favorite in terms of dramatic scenery. But I’ve seen a rattlesnake on it. Every time I pass by that place where I saw the rattlesnake, I’m super-alert. That rattlesnake hasn’t been there for 20 years, but every time I come to that place, I seize up. And then I meet people on that trail that I know.

BN: Are you enjoying the fall weather here in the Bay Area?

MM: I was hiking at Mt. Tam yesterday – it was so damn beautiful.

SL: I love this time of year – I think it might be my favorite. The grass is starting to come up, so you see that green glow at the edge of the path.

Would you like to add anything?

MM: If you don’t like our wonderments, find some of your own.

>> Special Offer for Bay Nature Readers

For a limited time, Bay Nature readers can receive a 30% discount on Wonderments. Visit Heyday’s website and use the code BAYWONDER. Offer runs through 12/31/14.

Visit Sylvia Linsteadt’s website, Wildtalewort.net to learn more about her ecology- and myth-based taleweaving.